X-Men: Kieron Gillen Sets the Stage for Sins of Sinister (Exclusive)

X-Men villain Mister Sinister is about to drag the entire Marvel Universe into a hellish future. Sins of Sinister begins in January, thrusting the Marvel Universe first 10, then 100, then 1000 years into a bleak timeline. The universe is its heroes are changed, with some new faces, and some iconic heroes like Captain America remade in Sinister's image. The story plays out across three miniseries: Immoral X-Men, written by Kieron Gillen, Storm & the Brotherhood of Mutants, written by Al Ewing, and Nightcrawlers, written by Si Spurrier. They're teaming up with artists Paco Medina, Patch Zircher, and Alessandro Vitti, each one rendering a different era of the timeline.

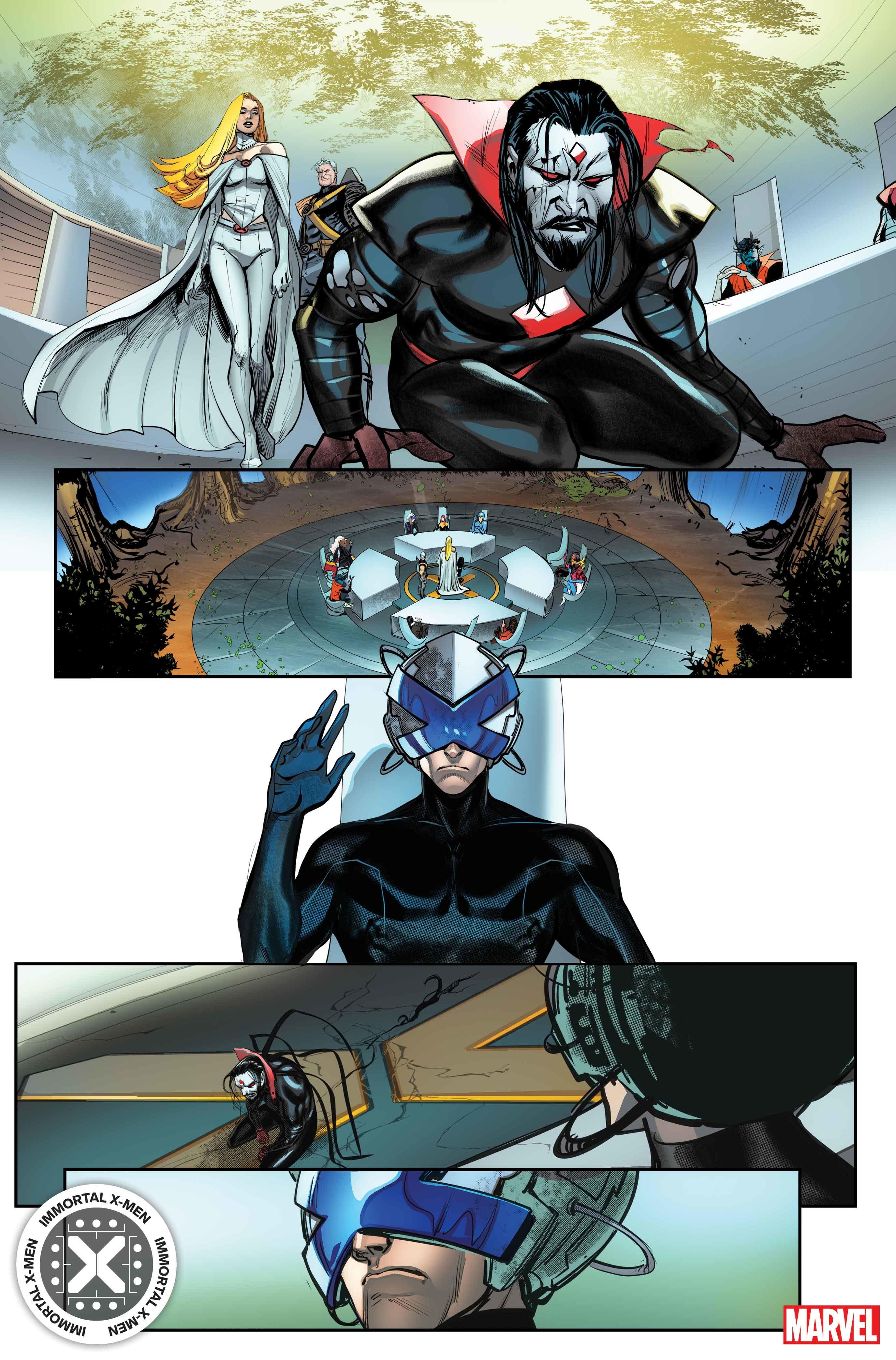

The first steps toward Sins of Sinister are taken in the pages of Immortal X-Men #9, which goes on sale today. ComicBook.com had the opportunity to speak to Kieron Gillen about Sins of Sinister and what it means for Krakoa's present and future. You can see what he had to say, along with preview pages from SIns of Sinister #1 and Immortal X-Men #10 by artist Lucas Werneck, below:

You've said in other interviews that, essentially, Marvel came to you and asked, "Hey, do you want to do the Quiet Council book?" That's how you ended up writing Immortal X-Men. How did Sins of Sinister become part of that? Was that part of the initial idea that you came back to them with? Did it grow out of a need as you were writing the story?

Kieron Gillen: Basically, I left the room for 10 seconds, and before Jonathan Hickman wanders off into whatever Jon's doing now, he basically threw a grenade at me. When I arrived to do Immortal, I was outside the office. I had an analysis: this is why I'm interested to do a Quiet Council book. This is what I want to do, and there's a lot of stuff floating around, and then, of course, Judgment Day changed everything, but the core of it's a quiet war of personality between Sinister and Destiny. They're playing hide and seek, neither being able to give away the fact that they both think the other person knows what they're doing, which has been fun.

Then it all builds towards Sinister's plans, which are an enormous climax at the end of the first year, issue 10, and then this big status quo. In my initial pitch, I left that open because I knew this is a big enormous thing that's going to absolutely define the book going forward. I don't want to say what I'm going to do yet because that's part of a conversation. There's one implied story that's so massive, and I'm pretty sure it was Hickman who said "do that." I mentioned it to Marvel and then suddenly it's become a crossover. I'm being told to do it in that way, but it's like, "Yeah, that's a great way of doing it."

The short of Sins of Sinister is it's a very different take on an X-Men classic, the alternate timeline, except this is not an alternate timeline. Due to the nature of the Moira engine, it's the future of the Marvel universe. It's just the future that may get blown up because that's what the Moira engine does. And it's also my gleeful homage to -- not mine, actually, it's me and Al [Ewing] and Si [Spurrier]. I actually forget which of us had the idea to basically riff on Powers of X. It's told across a thousand years of history in three time zones: 10, 100, and 1,000 years in the future.

The core idea, which I think Jon said to Jordan [White], was let's just do one of those timelines. Instead of doing a short time reset, let's go for a long one. Let's follow what happens at the end of Immortal 10 into a hell dimension. I joke that it makes Age of Apocalypse look like the Swimsuit Special and I'm not saying in terms of quality or anything. What I'm actually saying is, by the end of the thousand-year bit, it's so apocalyptically grim that it's gone straight into apocalyptically-grimly comic. It's really horrific, some of the worst stuff that three pretty horrible people can imagine, but it's got this enormous operatic grandeur to it. It's a lot. The idea came from "let's do a timeline" and we did.

Most of what the X-Men line is right now was built on what Hickman and company established in House of X and Powers of X. On his way out, Hickman did a kind of sequel with Inferno, which specifically felt like a sequel to House of X. Is it fair to characterize Sins of Sinister as the sequel to the Powers of X, to think of it that way? Or would you position it differently, or say that's a mischaracterization?

I can see why it would feel like that. The only reason that I would push back a little about that is that I know what I'm doing later [laughs]. I think the argument might apply better to that. I think this is very much dancing with it, especially with how in Immortal we start with two people sitting on a bench and having a conversation. I'm very explicitly in conversation with what Jonathan did, and that's where some of it came from, I think.

Part of the thrill of Powers of X was, here are some timelines that impact the nature of Moira in the present day, and there's certainly some conversation with that in Sins of Sinister. But at the same time, it's also the plot that we've been doing, the Sinister clones that Gerry [Duggan] revealed and then I added a bit more to in Immortal X-Men #8 and there's more to come there, shall we say. It's definitely one of those bits where people go, "Right, all these parts have been moving for X amount of time," no pun intended, and Sins of Sinister is where we start showing more, and with Fall of X next down the line, this cascades into that.

Moira is a wonderful device for making these timelines in Power of X impact our timeline. It's the same way in Sins of Sinister. In fact, we do have the Moira engine. There's at least one very clear device for how things "come back." And that's the thing, it's not an alternate timeline. This is part of everyone's game and these things will haunt people. I just named the last issue, the Sins of Sinister: Dominion issue, and that's probably called "Infinity Deadly Sins," which speaks a lot to the tone.

Having read Immortal X-Men #9 before this interview, I'm enjoying your characterization of Mister Sinister as something like a hack writer who sees Moira as a device but doesn't understand the meaning or anything beneath the surface. That's how he treats Moira, which I think is really fascinating. The issue is a lot of fun because it's this deranged remix of HoX/PoX's Moira X issue. Could you talk a bit about your characterization of Sinister in the series, and how he plays with those devices and concepts that were put in place leading up to this?

My core idea goes all the way back to when I rejigged him. I positioned him in the 19th century, his origins. Very clearly, he is a creature born of 19th-century philosophy. He's a British colonialist. He is somebody who sees genes and views them as a resource to be exploited. Most X-villains are quite anti-X-Men, and Sinister is not. Sinister really thinks the X-Men are important, he just thinks that people don't matter. Only the X-gene is important to Sinister and they should be his because he knows what to do better than them.

In some ways, Sinister is a wonderful dark mirror to Krakoa. The mutant circuits are some of the best stuff, I think, in this era, the idea that there are ritualized ways that mutants help each other, and that's what Sinister does with the chimera, but it's utterly unethical. Sinister literally objectifies people, and that's one of the many sins, but a core one, with Moira. He's taken a woman and objectified her, and that's something that Sinister's done time and time over. There's a real trend of taking very powerful women and removing their agency.

As light as I write Sinister on the surface, he's light so you can approach these real awful things. The great joy of Sins of Sinister is, as much as it's his universe, he's not having a good time. He's not enjoying it one bit.

When I was doing an interview a while ago, I was talking about how you get, in the first issue of Immortal X-Men, he's very, very smug and then Destiny just throws a wrench in his plans and he's got crap. That's the fun for me for Sinister and why I like writing him. It's not that he's not as smart as he thinks he is, but that it's the sort of smart that isn't good enough for what he wants to do, and that no one's that smart. That smart doesn't exist. My wife was walking past the interview and I was talking like this and she goes, "I bet it's Fraser, isn't it?" He's this over-intellectualized guy, and the whole thing is just seeing him falling on his face quite a lot, and that's Sinister.

Immortal X-Men #9, I think, is obviously high camp, over-the-top. As you say, "The X Deaths of Moira VII," it's this awful, deconstructionary, brutal joke. It's Deadpool with a Ph.D., that issue. But you still get to see Sinister killed 9 times. Sinister is the guy who comes out worst.

That's part of the fun for me with Sinister, and it's doing really well, but for me, the joy of Immortal is the tonal shift as well because, as playful as issue #9 is -- and you've got to be quite playful to have that amount of murder, otherwise, it becomes incredibly grim in a different way -- issue #10 is incredibly serious. It's the aftermath. It's from Xavier's perspective. They've killed Hope. Can Krakoa continue? And that's played straight. That's the push and pull of that book.

Sinister is really the villain, and I'm clearly somebody who likes villains. I've written a series of what I think are quite good villain books, and Sinister is one of the protagonists. I think that's the best way to describe it, the way that people in Game of Thrones were protagonists. It doesn't mean you're on their side, but I'm really enjoying heading toward the apocalyptic events which he is setting in motion, which is not good for anybody.

What can you say about how these couple of Immortal X-Men issues that serve as prologues relate to the Sins of Sinister main event? You've kept under wraps what the big inciting incident that sets this timeline off is, but can you say anything about what fans should be looking for as that approaches?

The opening of the trailer is Sinister's going in the pit. We've seen that preview cover, we know it's going to happen, and he goes in the pit. They've defeated him. That's after everything's been brought down.

Sins of Sinister skips forward 10 years and the entire world is basically being ruled by a Sinister-like Krakoa, and that's the thing. I don't want to say the how because the how is the story. Sinister's lost, but in 10 years, how is it he's won? And then, of course, as I said, no he hasn't [laughs], but that's the vibe. How the hell has he pulled this off? In fact, you might know the method by the end of issue #10, but then all the real details, that's in Sins of Sinister #1. Then you get to see the 10 years of very careful things that various agents pull off.

Then we skip forward and the structure of Sins of SInister is 10, 100, and 1000 as per Powers of X, and each one of them has its own very clear vibe. 10 is when we pick up and it's very, Invasion of the Body Snatchers is the best way to describe it. It's all slightly off. It's near-future cyberpunk. There are comic elements because it's a lot but also, it's pretty grim and relatively grounded, or at least Marvel grounded. Everyone's 10 years older. The humans have gray in their hair. Mutants are immortal. They don't have to worry about this stuff.

100 I'd describe as evil Star Trek. The Mutant Sinister Empire has gone intergalactic and they're starting to reach out into space finding strange new worlds and destroying them.

And then 1000 years, everything's gone berserk. It's warring empires of mutantkind filling the galaxy with screams. Warhammer 40,000 is my go-to comparison for it just because it's so operatic. I think that's a pretty good one.

You start at a very low-level conspiracy vibe. In the middle, you've got evil space opera, and then a far future of full-on gothic, operatic horror. That's the vibe of the three, and then we end on Sins of Sinister: Dominion to round it all off.

I was going to ask about how you characterize the themes and the genre of the thing, but it sounds as if each year is its own. They've all got sci-fi elements, more so than your average Marvel superhero comic, but to different extrapolations depending on which year we're looking at.

Yeah, you've probably got a taste of it in Immortal X-Men #3, when you saw a timeline with Exodus and the Shaw-batteries and all that. It's a bit of that. You see mutant technology pushed to the extremes. What could Sinister do with a lot more leeway than he has? And the answer is nothing good.

The way you're talking about Sinister, it sounds like this is just the most epic, generations-long pratfall in motion because, as you say, it never works out the way he thinks. It seems like this is him on his highest high, which means there'll be a long way down.

Way back in issue #1, when he's cloning his Moiras, he's using the experimental method. He's experimenting with the future and then he resets and discovers what he can. This is basically an experiment that got a bit out of hand. My original pitch document metaphor -- me and Al's pitch document; we did both work on this bit -- is "Year +10: a Petri dish experiment. Year +100: Oh no, the Petri dish is cracked and the goo is now all over the table. Year +1000: Oh no, the lab is full of goo, it's breaking down the door, and we can't stop it." That's what I mean by the experiment going out of control. It's got that kind of vibe but it still feels really "X"-y to me. Yes, it's science fiction but it is always X-Men science fiction. It's Sinister who's all about the mutant powers, which means that it's all about centering mutant identity and what mutants could do. Not in good ways, but in interesting ways, certainly.

I know you're someone who thinks big picture about comics as a medium and the meta layer of things. Do you have thoughts on what the purpose or function of these alternate universe-style stories are? I know you mentioned Sins of Sinister's a little bit different because it's not like Age of Apocalypse, where essentially you're going to shut that door later and come back to where you were. This is something that's more baked into the main timeline. But are there things that having these pocket universes, pocket timelines or extrapolations let you do narratively that you might not be able to get away with? Is it just a matter of extremes because things are going to be able to be reverted later, or is it something else?

I think honestly you make a good point there and I think the culture at the moment has an interest in the concept of parallel timelines and alternate dimensions, and I think if you're going to trace it back into something Marvel, what you're really talking about is What If…? The What If…?'s were like, "Let's take the timeline and say something else different happened." "What if?" is the core of an alternate dimension

But an alternate dimension story, an alternate timeline, is often rooted in the past. Age of Apocalypse is, "Something happened in the past and now we are here and it's the same time." Ours is just forking into the future. It's more like sliding doors but one door leads to February 2022 in the Marvel universe and the other door leads to hell.

And that's the appeal of the "What if?" of it, and that's the appeal of all these multidimensional stories. How else could we be? If certain things change and we extrapolate outwards, how else can we be? And the great joy of doing this with such a large canvas stretching forward, in the case of Sins, is we're really taking it out there, the idea of "What is the end? If we carry on doing this, what happens?"

For me, as somebody who just likes stories, that's part of the fun of a story to me. "What about this?" And then we just play with it and we can take things back from it. I'm heading toward talking about what we take back and how it impacts the present of what happens next in the X-line, but that's very key for me in terms of what this is. It's not an alternate future that happened over here. No, It happened. You've got to say that, presumably, it resets. I don't want to say that's a thing, but people presume there's something like that. But it still happened. We did it. If I just shot you now and then reset time, I still shot you, and I guess that's why, in some ways, the title Sins of Sinister works really well. This is all a dimension of sin as begat by an awful thing that Sinister has done.

Do you think there's a reason that for some reason the X-Men versions of those stories seem to be the ones that are always the prime examples? Pretty much every character has had some alternate future, alternate dimension story at this point, but it feels like when people reach for an example to explain what they're talking about, it's always, "It's a 'Days of Future Past' thing" or "It's an Age of Apocalypse thing." Do you think there's a reason that the X-Men seem to lend themselves to it or did they just happen to get the good ones early on and it stuck?

I think honestly you hit the real answer second. Yes, they did it best first. That means that they get ownership of it. But at the same time, thematically speaking, the X-Men is about the future. That's the "These are the children of tomorrow" aspect. In other words, it's always asking, "How will the world end up being?"

And also the X-Men, I think, of all the major comic franchises, are the one that is most necessarily embedded in reality. We talk about the mutant metaphor for many forms of marginalization and that has to be about reality. In the same way, my favorite issue of HoX/PoX was issue #1 of HoX, when Magneto is facing down the diplomats. That's a pure X-Men beat in the same way as, "How bad could things get?" and also, "How bad could things be now if someone else got into power?" Days of Future Past is born of a political change.

The fact the X-Men is grounded in politics like that does make it thematically interesting. And, as I said also, the nature of them being creatures of the future. If the fear of humanity is that mutants will become the future, we've got to look at the future, I guess.

I want to ask specifically about Immoral X-Men because that's the one that you're writing yourself.

I'm grinning. I still laugh that I got away with that title.

You mentioned the mutant metaphor. In the solicitation, the blurb for the first tissues talks about how the world now loves and adores mutants, which seems opposed to how it usually fears and hates them. Is that primarily a fun hook, or are you playing with the mutant metaphor, turning it on its head in some way, in this book? What specifically is Immoral X-Men toying with and how does it relate to what you've already been doing and will be doing in Immortal X-Men?

I must say it is more being playful with the core iconography of the X-Men. I don't think Immoral X-Men says anything, particularly, about the mutant metaphor. Where it is useful is in terms of the specific awfulness of the current Krakoan story. It's most interesting as, "Let's say Krakoa was bad," because people argue about the nature of Krakoa, but this is like, "What if it was actually really bad?"

I think in some ways the "What if?" makes you think about the "What is." What Immoral X-Men does is continue the Quiet Council nature of it. When I say the Quiet Council, what I mean is the political nature, the high-level politics, of whatever the Quiet Council is in the future. That's what it is because it really is a continuation of Immortal X-Men. In a different universe, it could have been Immortal X-Men with the numbers, but I stressed, "Don't do that. It works very well as its own statement." It does a lot of the big level political picture. It does a lot of the battles between the people in power.

I suppose the title really does do with the heavy lifting. "What if they were bad?" I think about how lucky they are that the X-Men are good, and that's for the X-Men as well. Xavier talks about this a lot in Immortal X-Men #10 in terms of "What's the purpose of the X-Men?" And the purpose of the X-Men is, in part, to be good and save people. And then, what if they're not? That's an awful hole we go down. In terms of the alternate timeline aspect of things, that's the awful "What if?" of it. It's the Peep Show meme, "Are we the bad guys?" And would you recognize if we were the bad guys?

I'm chewing over what metaphorical aspect of this there is, and I think people will probably make their own minds up by the end because, despite the fact that the universe has been set aflame by Sinister, there are definitely elements of heroism in the book. Storm & the Brotherhood of Mutants and Nightcrawlers feature real heroism, but they have very different features of that examination of heroism. Mine has pretty terrible people but occasionally you're rooting for some of them. That's what Immoral X-Men does, and there's a lot of black comedy.

I don't know if you intended it this way, but when all the revelations about Krakoa first came out, there were a lot of X-Twitter corners that were like, "The X-Men are all supervillains now." It almost feels like you're saying, "Let me show you what that would actually look like."

I think there's a lot of that to it. You just do this interview by yourself. Your answer there was better than what I blurted out I think. "You want to see what bad looks like? Let me show you what bad looks like."

At the most, Krakoa has gray elements. When Jon made this stuff, he wanted people to talk about it. When I was writing Judgment Day, I wanted people to have takes. I didn't want everyone to go, "Yeah, I completely agree with the guy with the thumb." I want to hear people go, "Bullshit, that guy should have passed" or "She should have failed" because that's the point. The point is to be an active reader and question.

You mentioned the Sinister clones thing, where there are apparently four suits, and four different lineages running around. Is that a thing that you had planned that Gerry Duggan just got to reveal first in his X-Men book? Is it a joint thing? Does that tie in at all with what's going on in Sins of Sinister, or is this something to be dealt with once these particular cards have fallen?

I would love to just say "yes" and that's my whole answer, but that's not my style. I must admit, I can't remember exactly where in my Immortal pitch I wrote what I'd written because there's a variety of stories going on. People know my Sinister -- let's call him Mutant Sinister -- his plan. We know part of it, the Moira part. We don't really know his other plans because what he's trying to do, that's still obscured. You'll find out in Sins of Sinister.

In terms of making there be four, I'm going to give the credit to Si Spurrier in the room because when we are talking -- Gerry, please correct me. I almost want to check with Gerry before saying anything because I think when Gerry was introducing Dr. Stasis, I'm not sure he had a club on his head. I think that might have been Si going, "Let's do four of them" around the office, and then suddenly that was immediately like, "That's an amazing idea. Let's do that."

But then of course it became "What are the four? What did they mean? What do they represent?" Gerry had Stasis be basically a human-obsessed Sinister. He's very into human stuff instead of mutant stuff. The question became, "What are the other ones into?" Now that Immortal X-Men #8 is out, we've had the backstory. This is how it came to be. This is the creation of these four beings and why they were created. The fact that's in play now, that's the stuff we explore in Sins of Sinister. I can't really say much more than that. They're all big players, because as the dear departed Nathaniel Essex said, it's survival of the fittest.

Can you talk at all about what keeps you coming back to Sinister? You reinvented him during your previous run. He's been built upon since then but he's such a fascinating character to me because I think his original origin was supposed to be that he was another mutant's imaginary friend.

Yeah, in the orphanage.

He's been through so many readjustments over the years trying to get him right. Why do you think he's been a character that you and others have kept trying to keep relevant as opposed to just thinking, "He's weird, let's leave him alone"? Because it's not like characters aren't abandoned that way.

Sinister, bless his cotton socks, being around in the '90s -- he was around before but as big as he was in the '90s, and having been fairly prominent in various other media forms, people at least know him, and it was kind of like, "People know him, we must be able to make him work." This is a look behind the scenes and the sheer practicality of writing a comic book. When I was launching the second volume of Uncanny X-Men, me and Nick Lowe were talking about, "What villain are we going to have?" And we generally talked about what villains are around and haven't had much play recently. And we went through and Sinister was the one where he was dead and he was available. So it was like, "Okay, Sinister I guess." And I went away and just did the heavy lifting on Sinister.

I'm sure one day Marvel will print my document I pitched my idea for Sinister in. It's a classic 5,000-word piece about, "This is why I didn't think he works. This is what I want to do with him." And as is pretty usual for most of my documents like that, it's probably about five times as much stuff as you need. And in reality, I did all that stuff in my run, and then the stuff that actually lasts from my re-imagining is the good stuff.

You lean into the drag queen aspect of Sinister, the larger-than-life aspect. I was writing him as Oscar Wilde. Not just Oscar Wilde, but Oscar Wilde as British imperialist. People have generally written him as more modern than that, but that was the vibe. I wrote him as very 19th century and with other people, that changed. The other thing when I reinvented him was like, "Oh no, he's rewriting his personality all the time." I was always aware that people who wanted to go back could because he could just load up an old personality and any change is him saying, "I'm just being this person today."

He is just the portrait of Dorian Gray if Dorian Gray is long dead and the portrait lives on. That's what Sinister was for me and all this other random stuff I built into him like that Sinister is a system, everything is Sinister, the idea of multiple Sinisters, that stuck and just the basic, "Oh, he's into genes." That's his superpower thing. He weaponizes mutant genes, and that's just really basic and Frankenstein-y. He takes Cyclops' eyeballs and pops them in a gun and shoots them at people. That's fun. But also it's campy and also, despite being quite joyous in that way, obviously, it's still creepy, but it asks questions to the X-Men. As I said earlier, the point of Sinister for me is he's a mutant villain who completely loves mutantkind…as pets. He thinks they're really interesting and they should be his.

Krakoa says, "What's important about you is you're a mutant. We will welcome you as long as you have an X-gene." If you really want, you're saying, "Only having an X-gene matters," and Sinister agrees with you. Sinister thinks the X-gene is the important thing about every mutant. In the classic Batman-Joker way, there's a really nasty question implicit in Sinister as in, Sinister agrees with you but he takes it to a different end. That asks hard questions. He's still around because he's funny now and he's a proper villain and he does fun stuff in interesting ways.

Why did I pick him up? I picked him just because it's the Quiet Council. I was asked to do a Quiet Council book. I'm not sure I would've deliberately pitched a Sinister book if I was given free rein. I mean, I probably would've. Jon Hickman was basically trolling me on Twitter for a very long time in terms of he would be writing a Sinister book at some point. But for me, the real point of taking over Immortal was taking what Jon did, putting my own spin on it, and then taking it forward. All that momentum from Inferno is what I wanted to build upon. And that's why Sinister is the clear problem in the room. The problem is he's their original sin, to use the name of a previous crossover to describe our next one. The problem of that is there, I think, implicitly.

This is where metaphor's too strong a word because people use metaphor to mean fable and it's not meant to be Animal Farm. What I think the mutant story is about, or superhero stories generally, is a way to dramatize things that feel like something. Sinister is implicit for the original sin of any form of nation-building. There is always something nasty in the room you've got to deal with, and in this case, it's that guy. It's not like any real nation-building. No one's really got Mister Sinister in their country, but the vibe of it is there.

That's what I think it's interesting because, for me, I wanted a book that didn't let the mutants off the hook. I didn't want to make excuses for them. I like the problematic aspects. How many good people are on the Quiet Council? Quite a few good people are on the Quiet Council and they're really trying to make it work. Even the ones you don't like are trying to make it work. Can they? That was, for me, the heart of Immortal X-Men. "Can we be better? Because we're in charge now. We've got no excuses. We've got a country to run."

Basically, he was a good villain, and the way I write books, I like my villains to be active.

I went back and read this 2011 interview you did with Laura Hudson over at ComicsAlliance as you were launching Uncanny X-Men. I thought it was interesting because there's stuff in there like Cyclops' letter which reads, to me, similarly to Professor X's psychic broadcast at the beginning of Krakoa, and then there's Utopia, another island nation, and during the interview, you talked about how writing the X-Men then was interesting because they had some sort of power, but there's always this thing where you're jutting against the metaphor and you're trying to show change but you can't change too much because then they're not the X-Men anymore. How much of that still feels true with how you're writing the X-Men now? Do the lengths to which Krakoa has upended the traditional balance of power make it feel very different or even just the fact that you're writing a political group rather than a superhero team? I'm curious about how your experience this time around has differed.

When I was trying to write it, I was trying to write a quite serious geopolitical X-Men and it didn't always end up like that. My intent was, I was quite inspired by a lot of the 2010 riots in the UK and basically, people trying to find leadership in those sorts of places and not a lot of that reached the page just because of the nature of a Marvel ongoing comic.

I generally think Krakoa did what I was trying to do much better. Jon had enough space and took a really perfect swing at it and that's why it hit as hard as it did. And then it becomes a space you can explore. At least part of what Judgment Day was for me was Krakoa having been forced to look outwards a bit more because a lot of the problems are internal but not all problems of nation-building are internal.

That's why, as I said earlier, I have problems with the word metaphor. I think applicability or resonances -- "resonances" is the word I like to use myself, as in, "This has interesting resonances," because metaphor starts tying it too closely. You don't control what something is a metaphor for.

What you're reminds me of something I read recently by J.R.R. Tolkien about how he didn't like allegory. It feels very similar to what you're saying now, the idea that just because it's similar doesn't mean I'm trying to build a whole one-to-one thing here.

Yeah, it's definitely for thematic resonance. People say mutant metaphor but they mostly mean mutant allegory, and that's where it trips people up because Xavier isn't Martin Luther King and we all know this, but the second you say allegory, it becomes that, and it's not that. It's leaders of a different character. That's what people mean when they say that shorthand, it's just that the shorthand is incorrect if taken too literally, and that's what allegory always does. That's why I twitch around it.

I think putting mutants in a very different position and examining -- returning to an earlier question -- the "What if?" Krakoa is a "What if?" "What if we all decided to pull together and do this and put our feet on the ground and say this? Where are we now? What will that lead to? And that's what we're exploring. I wasn't in the room for the decision to extend the Krakoan middle act, but that's because it's just a really great step. It's what people loved, and there are lots of things about mutants and the "What if?" -- power fantasy is a tricky word because people talk about power fantasy in comics and they mean it as, "I can lift a train" but there are lots of different power fantasies. The idea that there's an awesome island I could go to with all my friends and we'll be together, we can do this and we wouldn't have to be afraid anymore, that's powerful too. That's a fantasy that's worth thinking about, and then lots of other things tie into that.

One of the things about the X-Men you've got to think about is I reckon if you went through the entire history of X-Men, they probably spent less time in the mansion than they did anywhere else because they're always going back to the mansion, but then they're always leaving it. I've been reading a lot of [Chris] Claremont's run and for most of Claremont's run, they're not in the mansion. They're in Australia or San Francisco or in space. They're constantly getting away from different status quos. X-Men is a lot more fluid than people often think despite such iconic elements to it.

For me, Krakoa is now like the Savage Land. I think it's just part of the Marvel Universe. It'll be around forever.

Unless we destroy it.

Sorry, that's not a good answer. I genuinely think Krakoa is really solid.

I know Sins of Sinister hasn't even started yet, but fans are always looking to the next thing and we know Fall of X is around the corner. What can you say about Sins of Sinister and its relationship to whatever's coming in Fall of X? Does it lead directly into it? Is there something in between? How does this domino hit the next?

I have three issues and an annual -- I don't think that's been announced yet, but annuals get announced all the time -- basically, I've got four issues I'm doing between. A lot of stuff happens between the two and it all feeds into it. Sins of Sinister I view as basically Volume Three of my Immortal X-Men run. It's a fundamental part of our story, and a fundamental part of the story is never not going to impact it.

There is a thing we say in the X-Office describing what happens before the fall as "the cascade." That's what Sins of Sinister is a part of. It's the cascade towards the Fall of X. And of course, we're not talking about Fall of X yet and what that means, but with the idea of these events slowly cascading beautifully together like grains of sand falling and moving and that's what happens -- Sins of Sinister is like the Gobi Desert.

Immortal X-Men #9 is on sale now. Immortal X-Men #10 goes on sale on January 18th. Sins of Sinister #1 goes on sale on January 25th. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

0comments