Videos by ComicBook.com

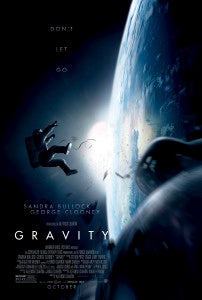

Back when I had only trailers to go by, Gravity (Directed by Alfonso Cuarón and starring Sandra Bullock and George Clooney), seemed like a total nightmare. Scenes of spinning space, no handholds and the endless void of space made my twitch a bit. The idea of watching it on a giant screen made my mouth go dry. Nuh-uh. No way. No thanks, got an appointment, can’t do it. So when the chance to go see it, in 3D no less, came by I jumped up and down and said yes so fast space debris would’ve missed me by a mile.

The jaded movie watcher in me just stuck close to the idea that I could go see a film that would impact me, and hard. It would be a visceral experience. I mean… look, watching Lone Ranger was a visceral experience, too, but I was hoping for something other than bile and despair this time.

But, and this is important, Gravity sort of has to be scientifically correct. It has to, really. The effects aren’t half as amazing if you don’t know that they’re also true to life. That said I decided to bring along my science consultant, Laszlo Xalieri, so that he could weigh in and see how they did. So you’ll hear from him throughout the rest of this and that will mean spoilers because you can’t talk about science in a vacuum.

Well. You can. But… you know what I mean. It was supposed to be a space joke, shut up.

GravityVideos by ComicBook.com

The sound field is spectacular. I can not say enough. When we get into pressurized modules and stations, out of a suit, sounds return as they should. But speaking of suits and being in and out them, let’s turn to Laszlo a second:

Also I bet those bastards pinch at the accordion joints. Also also, if you’re cold in your little unheated space capsule, put your damn helmet on. This will help trap your body heat in your suit, where it belongs. Especially if you’re in your underwear inside your space suit.Yeah. But let us return to our happy place and discuss the look of the film. The cameras spinning, panic-causing motion that was pretty much perfect. Objects in motion, and all that. It truly felt like you were watching someone drifting in space, with all the horror that applies. This movie will be responsible both for the number of astronaut dreams it inspires as for the number it shakes loose with a “Oh, hell no.”

I remember watching, as a kid, NASA videos on an IMAX screen at a museum. Gravity reminded me of that, except with far more “oh god oh god oh god” attached. That’s, if you were wondering, a good thing. No, it’s a great thing. This really is one of those rare films that needs to be seen big, if you can stand it. I recommend planning for a drink after.

Uhm, what’s that? Oh, hi Laszlo. Yeah, uhm… tell the nice people what they’ve won with that little idea:

There is plenty of junk in orbit. Lots and lots. Three thousand satellites and counting, plus all the dropped wrenches and loose screws. But, well, “orbit” isn’t just one place — one narrow ring a couple hundred yards wide and 250 miles up. Hell, even if it was, you’d have an average distribution of satellites of eight per thousand miles. That’s not a lot of traffic on the road for accidental collisions. “Orbit”, in actuality, is a spherical shell from about 60 miles up to 25,000 miles or more, and the altitudes you want an orbiting telescope at aren’t the altitudes you’d want a LEO space station or a military spy satellite or a weather satellite or an atomic clock for the GPS system.

Short version: You’re not going to have debris from one blown-apart satellite causing any kind of cascade, destroying other satellites and causing an ever-growing debris-field. Not until there are millions of satellites all elbowing around for room. And then there’s that other problem. Your speed, as an object that is not under thrust in orbit, determines the altitude of your orbit. A debris-field in your own orbit is only going to be a periodic threat if it is exactly in your orbit and traveling in exactly the opposite direction from you. (Hint: at 250 miles up, that period also will not be every 90 minutes). It’s not going lap you on your own orbital racetrack, because if it’s going that fast it will, by definition, be at a higher orbit. Or on an elliptical orbit that is tangent to or intersects your orbit, which would, if we bothered to bring the odds into it, only be a hazard every couple of years at minimum. If ever. The odds against any kind of random event becoming a quickly-repeating threat like the debris-field are, forgive me, astronomical. To me, the most believably dangerous debris was the odd ballpoint pen floating around inside one of the capsules. I was really, really worried about that thing ending up sticking out of somebody’s eye.Let’s start with the problem that the Hubble (which they were repairing/upgrading in the opening scene) orbits a hundred miles higher than the ISS. So the magic thrusters in Clooney’s suit’s jetpack has to handle changing their speeds at least by 180 miles per hour to keep them from being smashed into jelly in their suits or cut in half by the ISS when they get there — a maneuver easily achieved, I should point out, by a random split-second burn from the ISS Soyuz module to keep our heroine from smashing her capsule through a barely-orbiting Tiangong maybe 100 miles above Earth — toward which she was launched absolutely randomly, I assume, by the demolished ISS, because there was no initial burn to change orbits from the original ISS orbit. And then there’s the supernatural thrustless way a tumbling 1970s-Soyuz-style Tiangong capsule can orient itself for a re-entry attempt. Whatever the Chinese did to make that possible, we need to buy some of that for the rest of Earth’s space programs.

The difficulty of all of these maneuvers was no worse than leaping from platform to platform in an old 8-bit side-scroller, which killed most of the tension for me, in addition to being hugely disappointing in contrast with how much work they put into all of the rest of the zero-G maneuvering and the amazing soundscape. Small-scale 3D zero-grav maneuvering: dead on. Orbital mechanics: not even close. Here is an unpaid ad for the amazing Kerbal Space Program, to help you learn orbital mechanics: https://www.kerbalspaceprogram.com/ Also, here is the link to the amazing site Wolfram Alpha, delicately pre-encoded with how to figure out the orbital velocity for, say, 350 miles altitude above Earth: https://www.wolframalpha.com/input/?i=orbital+velocity+at+350+miles+altitude+above+Earth How much effort is that?But all in all, despite the problems, Gravity is the sort of film that should be seen, if only because the use of sound and visual will be stolen, adapted and enhanced for later films in strange ways. This is a movie that sets a marker down and we will learn more from it.

Also it’s one hell of a way to get your heart-rate up for 90 minutes.