In 2015, cartoonist Zander Cannon launched Kaijumax at Oni Press. Seven years, six seasons, and 36 issues later, the story about the lives of the inmates incarcerated at a maximum-security prison for giant monsters concluded with last week’s release of Kaijuamax: Season Six #6. The series was a massive undertaking for Cannon, who crafted the entire full-color comic book by hand, from layouts to lettering. His efforts paid off. Kaijumax became a critically-acclaimed cult classic for its beautiful artwork, fascinating characters, and delicate handling of themes involving corrupt systems and institutions that disenfranchise many while empowering a few.

Videos by ComicBook.com

With Kaijumax finished, Cannon looked back on the series in conversation with ComicBook.com, touching on his goals, process, and how his approach to the series changed throughout its run. That conversation follows.

Jamie Lovett, ComicBook.com: I guess the first, most obvious question is, how are you feeling now that this seven-year, six-season project is done and behind you?

Zander Cannon: No big whoop. [Laughs] I’m really relieved. I’m a little sad. I was talking to a friend about the series this morning, and it’s like, “Oh yeah, you know what? I do miss it already.” But I feel like I did what I wanted to do. I was going to start repeating myself if I kept going, and so, it’s a relief. It’s nice. One of the things about the series is that it’s so unrelentingly cynical, and I don’t think of myself as being an unrelenting cynic, so it’s a little bit of a relief to not have that construct of, I don’t know, sneering at everything to work through as the primary framework.

Not to force a metaphor, but was the prison series starting to feel like a prison?

Now we’re talking. [Laughs] I think any series you do for a long time, you feel like you’re doing things through the same framework all the time. I think you see it with certain things that last a long time, that creators changed their minds in the middle about what they want to do. I mean, Cerebus is an obvious example where it’s like he completely changed all of his philosophies in the middle of the series, and it became a completely different thing. Whether you changed for the better or for the worse, you’re going to look back at the beginning and go, “Well, that wasn’t what I was trying to say.” I mean, even with six seasons, it’s like, “Oh, the beginning’s different than the end,” but I’ll stand by it. But I feel like if I went for 10, 15 years, all of a sudden it just wouldn’t seem like it was the same anymore.

At what point did you realize that Season Six was going to be the last one?

That was planned from the beginning, strangely enough, with the idea that if we feel like it can sustain itself under its own power, six seasons would be what it was. Because I said to Charlie Chu, who was the original editor and the force to get it going., he’s like, “How long do you want it to go?” And I’m like, “I don’t know. Five seasons,” or “five series” (I don’t think we were calling them seasons yet). And he’s like, “How about six?” And I’m like, “Why?” And he goes, “Well, then you can divide it by two, you can divide it by three. It’s nice.”

Then later we discerned, “Oh, you can take two seasons to combine them into a hardcover and make three of those. That makes sense. It’s a better number. It’s easier to do stuff.” And I said, “Okay, we’ll do six issues for each one.” They really tried to push me to start making it five because a 140-page graphic novel and a 120-page graphic novel are essentially the same price point. It would make more sense to do five issues than six, but I don’t know. I’m difficult, I guess, so I just kept it at six.

You talked about how creators can change throughout a long-running series. I went back and reread as much Kaijumax as I could find time for before this interview, including the essay you put in the back of the second volume about how, where you say that you didn’t set out to make a social satire but you that’s where you ended up. You can see that a little bit in Warden Kang, for example, in the first season, is a little more heartless than how he is in season two, especially compared to Matsumoto. Once you realized that that’s what you found yourself doing, how much did that change your approach to the series and the stories you started trying to tell?

I think part of it was, I was trying to do something that was cynically mashing up two things, high concept stuff. You’re interpolating from what you think people want to read. I’d been like, “Oh, I want to do something with monsters. I want to do something about what they do when they’re not monstering and stuff,” and then I came up with that prison thing. But you’re thinking about, “Well, how’s that going to hit the shelves?” I think when I got into it, I started to realize how cruel and how coldblooded the idea was. Over time, I felt like I started to inject more of my own personality into it, which I hope is a little sunnier, but also a little more melancholy and a little bit more emotional, and less Rick and Morty, “See how I did that? See what I did there?” kind of thing. There are a lot of gags and a lot of tricks, but I really wanted to make people care about the characters and all that stuff. That’s a little bit more humanist, so to speak, than the original idea was.

So it became more of a drama because you were more invested in the characters? You started looking at them as more than fodder for jokes?

Yeah. Obviously, they start as chess pieces that need to fulfill a certain purpose. They’re there to be the antagonist. They’re there to be a philosophical counterpoint or whatever. But yeah, I wanted to make them into real characters that people actually liked. It was always a real surprise to me that people were like, “Oh, I really love Daniel, this sad goat,” pr, “I really hate this character because they’re so evil.” That’s an amazing feeling to have people, rather than just say, “Oh, your comic, yeah, I liked it. It’s fine. It’s good,” but instead saying, “Oh, I really like this character.” It’s like, “Oh, okay. Well then that means that I’ve really engineered an experience for you that you’ve really liked and you’re not just coldly assessing it as, ‘This comic is fine.’”

Did you find yourself getting that way with any of the characters? Did you become particularly attached to any over the course of the series?

Yes, but for a couple different reasons. Sometimes I just like them and I want to keep them around. But sometimes it’s like, “Boy, they’re useful.” I keep talking about a character called Ding Wing — the Giant Monster Terongo, the Terror of Pago Pago, as he calls himself. He was a really useful character. I think that he wasn’t a very deep character. He was pretty shallow. He was just a hustler or whatever, and the joke teller. But he was really useful because he was great in a scene because you could give him the button, that joke to end the scene with, or that he could always be pushing people. A lot of my characters are internal and numb, and so someone who’s a motor mouth will draw them out. So he was a really effective writing tool to have.

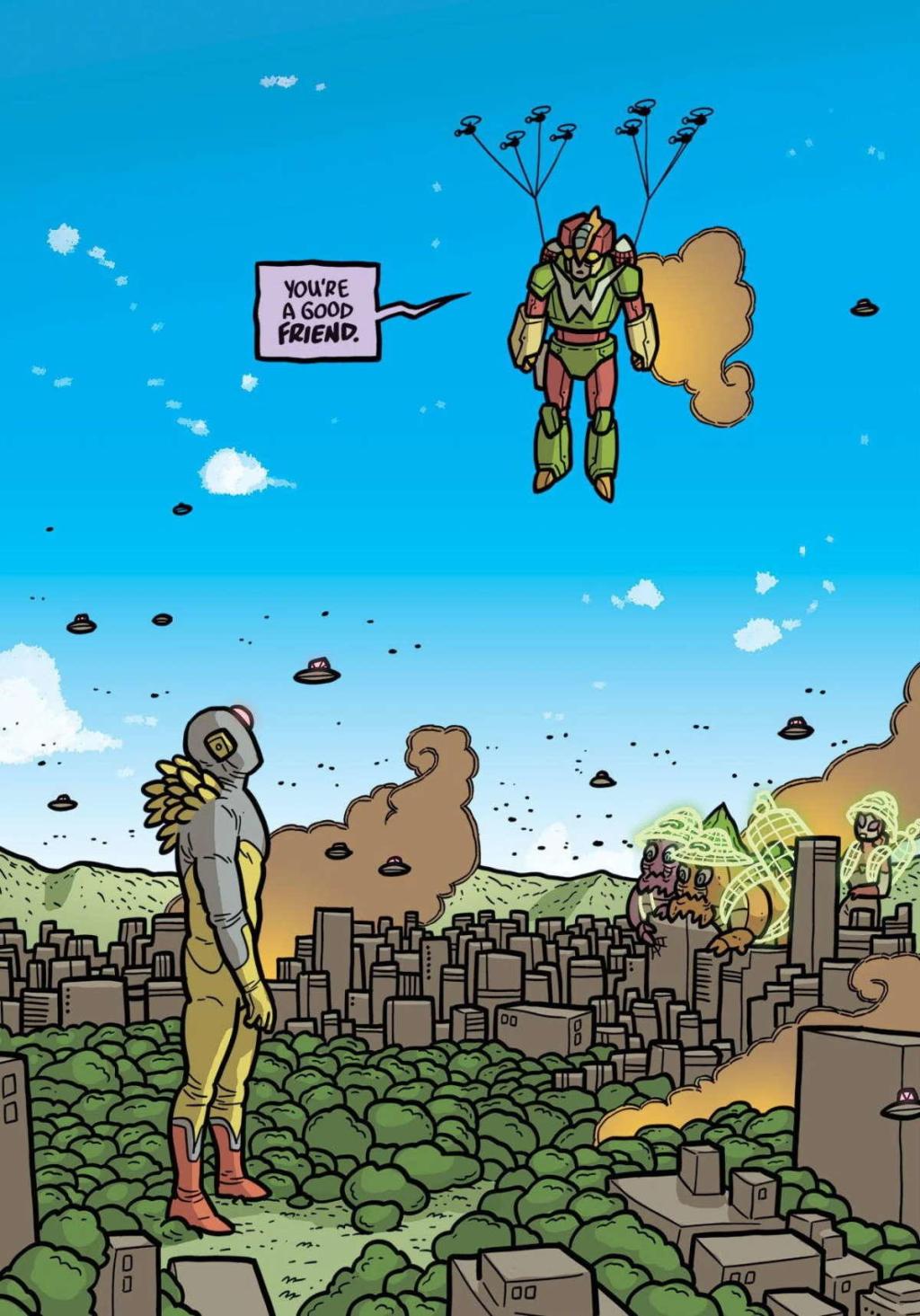

There were certain other characters, like the Lady of Lake character in the women’s prison who was trying to give people swords. She could be the person who’s drawing people out. Some of the corrupt guards are always pushing people — or characters, not people — but pushing characters so that they would react and do something active instead of passive. Also, I like the characters that everybody likes. I like Daniel. I like Electrogar. I liked Go-Go Space Baby and Dr. Zhang. I really liked their friendship and I liked how that was going, and of course, I had to destroy it. The cruelty of the series never totally went away, for sure.

It was fun to see these characters and feel something for them. Even characters that were mostly bad, like Matsumoto. She represents the thin, blue line of cops and corruption and stuff like that. I felt like I worked overtime giving her a tragic backstory that could explain it a little bit. It was definitely an organic process to give characters backstory, to give characters humanity when they didn’t always start that way. Almost without exception, they started as chess pieces to achieve a certain plot goal.

I loved Kaijumax as someone who has only seen a handful of tokusatsu or kaiju things and has never seen a prison movie or drama, but those are two relatively niche dramas. Did you ever have any feelings of concern regarding finding an audience for a premise that — at the elevator pitch level — seems to combine two niches?

No, frankly, the opposite. When I started the series, we were coming out of an era in comics that had kind of an arms race of wild mashups — “Dracula vs. a Shark and a Bear” kind of things — and so something that was absurd and violent felt like an easy choice. Also, the fact that it was very clear and based on things where everyone kind of knew the vibes of — Godzilla goes to HBO’s Oz — was a big help in selling the series, both to the publisher and to the readers.

In the frequently asked questions you put in the last issue, you thanked Zack Soto, Sarah Gaydos, and Desiree Wilson as editors, but also for being someone to talk to about navigating some of the cultural avenues you were going down. I feel there is a discussion among creators right now where some creators worry sensitivity readers or even just reaching out to editors in this way somehow deprives them of some of their creative freedom. Could you talk at all about what those conversations looked like if only to demystify that process? Because it seems to be a boogeyman in some creators’ minds.

I don’t think it’s a boogeyman. I think that’s a great idea. The start of this book predated that being a common practice, and so in a lot of senses, they kind of let me do what they would. They certainly didn’t interfere in any way other than to say, “Well, have you thought about this?” A lot of it was more like, “This seems like it’s headed down a road that’s weird.” And I would say, “Oh, well, I’m going to go this way instead,” and, “Oh, okay. Fine. That’s good.” I think when you’re dealing with cartoon characters, for one thing, monsters for another thing, and something that’s so abstract from our society, you’re not in as much trouble. I think that you can always run into weird metaphorical things where you’re like, “Oh, I thought it represented this, but people thought it represented this, and I implied something cruel.”

I think a lot of the stuff that we had to worry about was this emerging consensus that cops maybe don’t have everybody’s best interest at heart all the time. The comic is full of cops as both heroes and villains, and protagonists and antagonists. Certainly, that was in my mind to say, “Well, let’s not lionize the thin blue line type of stuff.” I tried to stick to things that I knew something about. There’s a little segment about transracial adoptions, where the monster boy is adopted into what amounts to a white middle-class suburb. We’re adoptive parents, and my son is Korean. We drew a lot from our own experiences, but also from talking to other adoptive parents and hearing them say weird, low-key racist things that we don’t love, and so to not really have a thesis so much as saying, this is an imperfect system, and it’s imperfect in these ways, and hopefully, people can come out of it with their own choices to be made.

I’m glad that sensitivity readers are becoming a thing. I’m sure that does hamper some people. I think that’s the idea. If you’re about to blunder into something that’s racist or cultural appropriation or something of that nature, I think that you need somebody to tap you on the shoulder, especially middle-aged, middle-class white guys like me. I’ve been blundering into things my whole life. I could do with somebody to say, “Dial it back a bit.”

This was obviously a huge project. All these issues, six seasons, six issues each, and you’re doing practically all of it, though you’ve mentioned you had a color assistant and editors that were all helpful. What was your process like on this? Would you start with a script and work from there? Did you start by drawing the story out? What did your process look like?

I wrote one script for the first issue because it was going to be drawn by someone else initially. Generally speaking, what I would do is make a little board with post-it notes, and then I’d write out scenes, basically. Usually, I would say, “scene starts this way, arrow, scene ends this way, here’s some extra details.” Then I would color code them so that I could say, okay, well, here are the five scenes spread across the six issues of this character or this pairing or something like that. Then I’d think to myself, “All right, I’ve got it all. I figured out who’s in what issue.” And each issue, I’d try to bookend it with the same characters or have an A plot and a B plot, and then a C plot. And then, the C plot would become the B plot and the next one, and then become the A plot in the next one, that kind of stuff. Just moving pieces around.

Then I would go in and I would draw layouts. I would have a document open with 22 pages, and I would start making layouts. I wouldn’t even name them by the page number. I’d just name them like, “Zhang 1,” so it’s the scene with Zhang in page one, and there you’d have four pages or whatever, and then I could move it up or down a little bit. And then once that was all put together, I would start numbering the pages and I would pencil them in. Usually, when I was somewhere between laying out and penciling, I would start dialoguing it, because you realize how much less you need to write when the pictures are basically there, when the flow is there, when you get to say, “Oh, I’ll have to have a little bit of dialogue to just set up, set up, set, set up, and then the turn the page. Okay. Now, we’ve got the picture that answers all the questions that the words have been asking.” Then I can start to move the lettering into the word balloons and put it all together.

I would edit the dialogue until the very last minute, much to my own chagrin because I would hand-letter. The whole thing, the whole issue, the whole series is hand-lettered, even though I would use a computer. There’s never a piece of paper, but I hand-lettered it on the computer. I’m not going to try to tell anybody that’s a good idea. It’s really wasteful in terms of time, but I like it and it feels good. Once I had the layouts and the dialogue in, the pencils, inks, letters, colors, that’s no problem. I never sweat that stuff. It would all just take as long as it took, but it always took the same amount of time.

Writing could be over in an afternoon or it could take until an alarmingly late stage. I always thought that that was really interesting because I think that a lot of people think, “Oh yeah, writing is the easy part of comics. It’s the drawing that’s so hard.” Well, I’ve drawn enough comics that drawing comics is now pretty easy for me, especially if you’re not going to change art styles, you just draw it how you always draw it. But coming up with a good story was exhausting. That’s the best part. I don’t have to come up with any more stories about these guys.

You mentioned that you weren’t originally going to draw it. When you ended up taking on the art, what were the goals you had for yourself, and for the visual style of Kaijumax? I think, visually, it has this perfect alchemy of dark and light, and a lot of that is the coloring is so bright and beautiful, and then the story’s like, “Oh well, that’s unfortunate.”

“Unfortunate,” that’s a good way of putting it. A lot of it was, that’s the way I draw. I can only draw in one way and I can go a couple of degrees in either direction, but that’s about it. I do feel like it started off a little bit less stylized. By speeding up, I had to create a slightly different style. It had to move into cartoony territory. I would leverage the cartoonishness of it to make it absurd and sad at the same time or absurd and disgusting at the same time or whatever it needed to be.

I remember going into it thinking, “This is impossible. It’s impossible to do all this work.” But I had recently done this comic called Heck, which is black and white and it had been done not on a tight timeline, but I was doing it very fast. I started to realize you can scale back. You don’t have to do everything at the maximum detail level. You can scale it back and do it faster and it can be better. It can read better. It can be read more smoothly or whatever. And I thought to myself, “Okay. I can color things in a way that’s not quite so elaborate. I can ink things in a way that’s not quite so elaborate.”

It broke down a mental barrier for me where I could say, “Oh, I guess I can do this, all these things that I always wanted to do.” I always wanted to singularly create a series that I could set up and pay off all these stories and so forth. I felt like there was no way I could keep up because the gold standard was you got to get 22 pages done every four weeks. Kaijumax came out, at first, maybe every six weeks. It wasn’t much slower. And it’s like, okay, well, all of a sudden that’s doable. That’s not so bad.

And then from there, my art style, my personality started coming through, so it started to get a little more cartoony, a little sillier, a little more absurd. But also the speed that I was having to work, the hand becomes three little bananas or something way faster to draw. I changed up my writing methods, my workflow. I would pencil things at the studio and then I would take home a Cintiq, the plug-in one, a laptop type, and then I could ink while I was watching TV so I wouldn’t get bored. An extra hour of inking meant that the art looked that much better, that much more refined, and so the art started to get better. I started to find the best ways to keep engaged while I’m working, listening to podcasts or books on tape while I was penciling. I’ll still even be looking at a page and be like, “Oh yeah, I remember. I was listening to The Flop House podcast or whatever.” Or, “I was listening to the Dracula audio book or whatever, something weird.”

The character designs in Kaijumax stand out and are incredibly varied. Did you have a unifying theory or approach in mind for your designs? Did any emerge as a favorite, or did you come to regret a particular character’s design after having to draw them repeatedly?

I had a couple unifying theories. One was that I wanted all of the monsters to be, in one way or another, something that could be operated by a person in a suit (or a puppet in some cases, I suppose) so that they could all be more or less the same size and potentially fight each other. More than making it like what the world would be like if giant monsters were real, it was what the world would be like if the literal monsters from movies, and how they were presented in those movies, were real. I even had one call another a “zipperback”, just to drive that home.

Another tactic was that I really tried to design them on the page, and more to the point, design them sort of in the middle distance. What that did was that I tended to be more conservative in terms of how complex they were and how many colors they had. A character like that, if I drew them close up, could always have more details like scales or surface texture, but if I had designed them close up, it was tricky to decide what to simplify when drawing them in the background.

Some of my favorite designs were kind of silly ones, like Ding Wing or the Mongolian Death Worm, or the original Ape Whale. I like the ones that have a certain way that they stand, but have some flexibility in how they can be posed and move.

And I’m afraid I regretted a great number of designs over the years, mostly because they are too complex and hard to keep straight: the warden of the women’s prison is a lot to draw each time; she’s five different robots, all with different design and color schemes, and twice as tall as all the other characters. Exhausting. Any character with a lot of tattoos, like Pikadon or Hellmoth, was a lot of work to keep consistent; I ended up having one of Hellmoth’s arms get chopped off just to lighten the load. There are also a fair number of characters that are green and kind of hard to distinguish from the grassy hills in the background. That was just bad planning on my part.

One of the signature elements of Kaijumax to me is the dialogue and the use of kaiju slang. How did you go about creating that dialect? What goals did you have in mind? Were there certain pitfalls or tropes that you were trying to avoid?

Since I was making an effort to make the drama pretty straightforward, I wanted something that would inject a little humor on every page, and slang that had references to monster movie characters/concepts worked pretty well for that. There are a lot of opportunities in that sort of stuff to shout out my favorite stuff, or kind of signal to my fellow nostalgia-laden friends what sort of story I was trying to make. The main hope was that the dialect would kind of flow, and that there would be ways that you could kind of determine who would say certain things and who wouldn’t, etc. As for things I was trying to avoid, I felt like the series leaned into equivalents to racist (or reclaimed) slurs a little hard early on, and I backed off on that, especially since they would end up showing up in articles or headlines about the series with a lot more emphasis than I intended.

Something I noticed in rereading Kaijumax is there are several pages that feel like they’d be a cliffhanger ending in a Marvel or DC or Image book. I’ve read enough of those that my brain is trained to look at this big splash page revelation and think, “Oh, this must be the last page of the issue.” But you always keep going. Most of those comics, the way they’re paced, often feel like each issue is reading the one act of a television show in-between two commercials. But each issue of Kaijumax felt like a full episode. Can you talk about your philosophy for plotting out the story, dividing it issue by issue, and how much you wanted to get into an issue to have a beginning, middle, and end?

I never put it into words or anything, but I never wanted a cliffhanger. I never wanted to make it half of a story. I see the instinct in doing that. My God, it’s so much easier. If the story’s the hard part, then you can have one story over 40 pages. Well, you could just expand the scene, but I never wanted to do that because I’ve been a comic book reader for my whole life, and it’s really frustrating when you read a comic that’s just between commercials or just the latest seven minutes in some guy’s life or whatever. I find that to be really frustrating.

With the annoying framework of the seasons, it’s clear I was trying to make this like TV. An issue was an episode. It’s setup, rising action, climax, denouement, all that stuff, so that you could feel like, “Well, that was pretty satisfying.” It’s going to continue but I never wanted to set up a cliffhanger, because cliffhangers are always BS. You’re always hiding something that you’re going to use to resolve it and people will be like, “Oh, meh, that’s a cheap trick” or whatever. That kind of stuff drove me up the wall.

I seemed to be the only person who felt that way. It’s miraculous that I kept to it the whole time because it would’ve been very easy to just say, “All right, issues two and three are going to be a two-parter. Issue two’s not even going to really get anywhere.” That would’ve been easier for sure. But I’m glad I stuck with it because I feel like you could pick up any one of those issues and you’ll get something out of it. You’d be a little lost, but between the previously on and the stuff that people say to catch you up, I feel like they’re all pretty much something you could pick up by themselves. Not that it really matters because the individual comic books basically fall by the wayside and there are only trade paperbacks now because it doesn’t make any sense to go back and buy old back issues of something that’s been collected a bunch of places.

Do you think that changes at all with the advent of digital comics? It’s easier to find individual digital issues, though the digital trades are just as easy to find.

There’s going to be people who wait for the trades no matter what, and that’s great. I’m one of them for a lot of things. I tried to make there be no reason that that would be a better experience. I had a letters page. I had movie reviews. I tried to make it, this is worth your four bucks. If it’s a 20-page book that doesn’t conclude and doesn’t have a letters page, why would you buy the individual issue? Unless you cannot wait to find out what the X-Men are doing, or you need to cover it, I guess, for you. I wanted to make sure that it was worthwhile, that it was worth your couple dollars. I did hear from some people that this is the only comic that they buy. It’s anecdotal, but it’s the only comic where they buy individual issues and it’s great. I cannot ask for a higher praise than that.

Now that it’s finished, do you consider Kaijumax a success in your mind? Based on whatever metric is most meaningful to you: creative, sales, whatever.

Oh, absolutely. When we were negotiating it at the start, I really could have planted my heels and held on for a higher page rate and really played that out. That probably would’ve worked great for 12 issues or something like that. But this comic was, let’s say, a minor cult hit, and that will sustain a page rate that’s middling. I could have gone for higher, but I just wanted to finish it. I feel like it’s so much more valuable to me, if I’m not living paycheck to paycheck, to have finished the story and to have, eventually, these three hardcovers as this body of work that is indivisible. There’s no asterisk about it where you can say, “Well, I never got to resolve that thing,” or, “Yeah, it got canceled halfway through”or whatever. That’s the metric that I use. I’m so pleased that’s where we got to. I mean, it comes at a cost, a literal cost, but it’s absolutely worth it to me.

Well, thank you for taking the time to talk with me today. When can we next expect to see some Zander Cannon comics on the shelves?

I’m working on stuff at Oni. I’m doing some Rick and Morty covers, and I’m doing a YA graphic novel. Who knows when that’ll be out, but pretty soon. But I am working on a graphic novel itself. It’s not going to be serialized.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. All 36 issues of Kaijumax are available now. The series’ first five seasons are available in trade paperback. Kaijumax: Season Six releases in trade paperback on August 30th. Kaijumax is also available in two Deluxe Edition, each collecting two seasons of the series, with the third and final deluxe edition on the way.