That would be Batman ’66 Chapter 60, released almost two weeks ago and featuring gorgeous and intricately detailed art by acclaimed Superman: The Man of Steel artist Jon Bogdanove.

Videos by ComicBook.com

Bogdanove, who has spent the better part of a year working on the issue and who has a terrific Adam West impression locked and loaded to use when needed, joined ComicBook.com to talk about what went into the book and what makes the DC2 format special.

full issue on comiXology hereBogdanove has provided ComicBook.com with an exclusive look inside his process, which you can see broken down step by step in the image gallery at bottom.

Can you walk me through what the difference is between Marvel’s Infinite Comics and Thrillbent’s format and the like, and the DC2 books?

I think actually DC2 is a simpler reader than those two. My understanding of it is that DC2 is basically a comiXology reader that takes regular digital comics and gives them the added transitional mechanics of zooms and pans, so it’s not like Madefire or something like that. It’s not like Injustice. It brings the panel to life a little bit more.

It’s not a fully-animated medium. It’s still a reading medium, it doesn’t have a music score, it’s still the intimate reading connection of a paper comic but with some bells and whistles that bring it to life.

The challenge for those of us who have been lucky enough to work in it has been to really find within its capabilities the best and most creative ways to use it.

You had told me that the Batman ’66 issue you’ve done is something you have been working on intermittently for about a year. You have a lot of experience in other media, be it video games or merchandising. Have you brought some of those skills over into the DC2 stuff?

For people who don’t know, an animatic is – for guys my age, I guess the easiest equivalent would be the Marvel Comics cartoons of the early ’60s where essentially what the animators did was cut and paste Jack Kirby pages and add moving mouths. It’s a little bit like that, only better in a way because you’re controlling the presentation as you read it. But you can create an illusion.

If you’re willing to draw a panel multiple times, you can create an illusion of motion with your transitions. So for instance, depending on how involved you can be, you can add layers that change the expression of a character with every tap or transition. Or in some ridiculously ambitious moves, you can draw an entire new panel, which is actually more than drawing the cell because you’re drawing the background and you’re drawing all the detail.

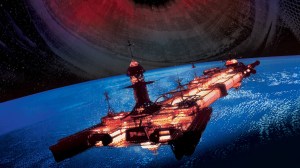

Batman ’66Well, I started to get into the spirit of this thing. The Batman TV show is a 50-year-old television show that in its day was cutting edge. They broke the mold on that show in a lot of ways and it was hip and innovative in its time. I was really tickled when I was invited to come draw an issue that here, a half-century later, this show is still innovating things in that the most innovative DC2 comics to my mind have been the Batman ’66 comics, especially the ones drawn by Jonathan Case, who really sort of inspired my approach. I think he was the first to recognize that this isn’t just digital comics.

We’re not just reading a PDF of a comic as you do on some readers. This is a new art form. So the challenge if you’re willing to accept it is to explore the capabilities of that new art form. What sort of reading experience can you give people that is unique to this, that is not just a projected version of a paper comic book and it’s not as passive an experience as a cartoon? What can you do with this that you can’t do with other things?

And the most innovative and ambitious and clever ways of exploring that new art form were being done on Batman ’66, and that really sort of intrigued and tickled the heck out of me. Because it’s based on a half-century-old TV show.

ROM SpaceknightThat’s a really good point. Honestly, there is an attraction to being in a self-contained universe. There’s the Batman ’66-verse, right? And it exists outside of complex continuity, and they give us tremendous latitude to experiment. Comic books, traditionally, have been a place for experimentation, and some of the best comic books, in my view, have been the ones that happen somewhere in the background and they just catch fire. Someplace where no one is paying attention, and artists and writers are allowed to play – and that in my mind generally creates the new ideas and the best innovations.

That’s sort of what Batman became. It’s sort of a testament to the character of Batman that he works in so many wildly disparate interpretations. The dark, gritty Dark Knight has sort of held sway for the last thirty or forty years, but it hasn’t always been that, you know? It’s like Adam West says: “They have their Dark Knight, but I was the Bright Knight.”

Batman/Green HornetAnd he said, “Pop, you gotta get some sleep.”

You know, I think if you’d been working a 48-hour workday DC would have been concerned for your safety and objected, but when you expand it to 52, they have to approve, don’t they?

Oh, my gosh! I never even though of that. That’s part of the DC canon now.

To answer the question that we kind of spiraled away from, in the spirit of innovation that characterizes this book and the weird TV show that inspired it, this is one of the first comic books I’ve done entirely in digital. I’ve been working completely on the Cintiq pad. I’ve used the Cintiq and Photoshop a lot in the past, but usually as an adjunct to paper art, because I enjoy drawing on paper and I have a little greater mastery on paper.

But you know? It’s a digital innovation and I was trying to embrace that and it’s a very innovative comic book and I’m trying to embrace that, so I said, “Alright, let’s just do it all on the machine.” And that is what gave me the ability to go in and get the kind of detail that viewing on the iPad screen really requires. Digitally, you can go into the pixel level if you want to. So I was able to get caricatures and expressions on characters that, in the printed version, you won’t even be able to see them. You’ll know that that’s a henchman back there, but you won’t know that he’s doing a goofy bit of business. So in a printed comic book, I could have gotten away with just a scribble and in this one, I zoomed in and created a character with a backstory and a life and gave him stuff to do. So there’s a lot of work. There’s a reason this thing took so long. There’s a lot of imagery to play with and enjoy in the book.

Is that one of those things where you toss your friends and foes in?

Yes, and there’s a lot of that stuff going on. There may be, some of my friends may see characters that resemble them as innocent bystanders in Gotham.

I have a tendency to get obsessive about the backstories of characters because honestly, I think it takes longer to draw than it does to write by about a factor of ten which I think is why a picture’s worth a thousand words – because it takes as long to draw a picture as it does to write a thousand words. So I do tend to imagine backstories for all of the characters when I’m drawing them and I think that sort of helps bring them to life.

That may be accentuated by the fact that we’re working in the Batman ’66 universe where things are a little bit more lighthearted and a little more character-driven and less plot-centric, you know what I mean? You kind of know what the pattern of the plot is going to be on a Batman ’66 story, whether it’s the TV series or the comic book. It’s going to be split up into chapters, there’s going to be a cliffhanger, there’s a sort of reassuring, formulaic structure to the stories, so what you’re really in it for is the gags and the character bits, and so there’s wonderful latitude to play with character bits on characters that are not the main ones in the script. Just little incidental people in the background. And there’s also a lot of freedom to sort of play with humor in a way that certainly dark Batman, you can’t do very much.

So the Batman ’66 villains are just so much fun, you know? It’s sort of a parody of comics of the time. I don’t know how much you know about the show, but William Dozier got the assignment from ABC to do a show based on Batman. This guy grew up not reading comics, so he actually didn’t know what Batman was. So he got a bunch of comics from DC, and this was the silly ’60s, when there were Bat-Mites and Rainbow Batman and all kinds of zany, strange stuff and beautifully stylized artwork by those Silver Age guys like Dick Sprang.

So he came at it straight and at the time, certainly by the time I was a teenager, I had no interest in the camp Batman. I was into the [Neal] Adams Batman and we were just realizing the serious potential in that character. But that’s not what the show reflected. The show reflected what was actually being done in the comics and it was like an outsider trying to objectively translate that to television as best they could.

And there was a very conscious effort on the part of the TV show to look at the show as pop art. At the time, Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein were popularizing media imagery. Roy Lichtenstein, in particular, is well known for just blowing up comic book panels to giant canvas size and – bang! – calling it art, right? So the show’s producers looked at Batman from the outside and decided to approach the show as a piece of modern pop art.

And so they did, and some of the shows hold together better than others, but if you look at it from the standpoint of art history, kind of see what they were going for. So part of what attracted me to this and part of what I luckily got to play with because of the nature of the villain was some of the art movements of the ’60s, which were vibrant and plentiful.

For instance, there’s a device where Marcia, Queen of Diamonds, comes back to Gotham and convinces the rich people of Gotham to give up all their treasure, right? Oh, dear. And the way she does that is with a hypnotic device. I got the idea to represent the hypnotic psychedelics in various art modes of the 1960s. So I play with mod art, I play with a little pop art, I play with a little op art, I play with some psychedelic art, I play with a little sort of mid-century modern repeating pattern designs and so I really had a chance to evoke or at least suggest various different types of modern art that were happening at the time and which influenced the show. So in that way sort of trying to bring it full circle.

The show was an outsider’s view of comics of the day and the comic book is an insider’s view of that TV show. And it makes for sort of an interesting Bat-ouroboros of cultural impact.

What is the biggest process difference for you in this format versus your traditional books?

Well, the biggest difference for me was trying to figure out within the capabilities and limitations of the technology new ways to tell a story visually.

Technically, drawing on a Cintiq isn’t a huge thing for me even though I rarely work entirely digitally. But the real thing was figuring out “Okay, what can we do? I mean, besides having a character’s arm move from A to B in a transition, what else can we do?”

Can we, for instance, show simultaneous changes in several different panels at once? In other words, rather than just layering on the next panel with the next word balloon and leaving the previous panels frozen in time as you would with an ordinary comic book, can things continue to happen in those previous panels even though the story is moving forward?

So I sort of developed what I’m calling “omniscient view,” where the reader can look at an entire page and with each progressive panel, things continue to happen in the previous panels.

So for instance, if there’s one scene where Commissioner Gordon is walking form his suburban house to his car on the way to work and Batman and Robin are trying to intercept him, in the first few transitions we see Gordon step out of his house and approach his car. At the same time, we see Batman and Robin get off a city bus — don’t ask! — and cross the lawn, and then we switch to panel two and we see Gordon in the car in an interior shot in panel 2. But back in panel one, he’s no longer walking toward his car, he’s not inside the car, and Batman and Robin are walking to the back of the car doors.

And then the panel changes and in panel three, we see Batman and Robin get into the car and back in Panel One, we can still see them getting into the car. And in Panel Three, we see the car pull out in another transition and it drives away — and still in Panel Two and Panel One, we see what would be happening there, which includes just a shot of Batman and Robin sort of whistling as they drive off.

But what it does is, it allows a multiple view of the action in any scene that you can’t get in cartoons and you can’t get in a paper comic book. It’s almost like you’re watching the scene on a number of different cameras at the same time.

So that’s the kind of innovation or trick or gimmick, whatever you want to call it, that DC2 sort of allowed me to invent – and it’s something you can only do with DC2. You can’t do it with a typical comic book reader, it’s not something you can do in a printed comic book. It’s an attempt to create a new art form, and that’s the biggest technical challenge and it’s oddly enough the theme of this weird Bat-ouroboros of the Batman ’66 comic book.

I feel bad that I never mentioned my background assistants. I am paying MadPencil Studios in Mexico City to be my background team. The studio, run by Roberto Flores, has been inking backgrounds, and in some cases drawing them for me on this job.

The way that works, process-wise, is this:

After I design the page, build all the transitional mechanics, pencil and ink the artwork and build sound effects (lifted almost entirely from, or designed to look like the signature SFX from the show), I send each GB file (lots of layers, initially. About half a GB after I do a final assembly pass) to Mexico. I provide the guys with reference and pencils– but the completeness of the pencils I send ranges from complete, full pencils to just a perspective grid and some scribbles.

Sometimes, I will pose CAD models of period vehicles or houses, and either trace them, or make notes about changes. The big spread of the chase scene on pages 9 involved all of the above. The cars were all inked from either CAD model reference or photo reference off of the web. Gotham’s version of L.A.’s Angel’s Flight funicular RR, and surrounding cityscape, was traced and inked from a complex collage of period photo reference, full perspective drawn pencils and rough pencils and grid lines with notes on embellishments. A huge production for one panel.

Many of Gotham’s “innocent bystanders” were friends and loved ones who agreed to pose or appear in period dress. The kids in panel 2 were drawn from my own childhood memories– including a fairly accurate portrait of the artist as a young geek, in typical idiomatic school-day attire.

I’ll see if I can attach the print version of that page. Hang on… Got it! Here’s a 400dpi jpeg. Even more is visible in the DC2 version.

Also, because the show was so strongly influenced by the Pop Art and Op Art movements of the 1960s, I wanted our color palette to reflect the period. I also asked that MadPencil incorporate some of the tricks and techniques originated by Jono Case to convey a PopArt feel. The use of BenDay, dot-matrix graphic patterns and slightly off-register blue-line are characteristics of the way Jono paid homage to the era’s art happenings that shaped the Batman TV show.

MadPencil has, so far, done a brilliant job. Their colorists “get” the period and the palette perfectly. They’ve also studied Jono Case’s stuff and have used his tricks without over-relying on them. I hope Jono doesn’t mind his influence on us. I think it helps tie our issue in with the rest of the run.