Comics is the perfect medium for big concepts and fantastical imagery. It can bring a creator’s imagination to life without a massive budget or the interpretation of prose. Dark fantasies like Hellboy and The Umbrella Academy are perfectly at home in comics because they can do whatever they want without sacrificing any facet of what lies within the artists head.

Videos by ComicBook.com

Neveryboy #1 sounds like the sort of idea that should naturally seize upon this potential. Writer Shaun Simon and artist Tyler Jenkins are telling the story of Neverboy, a former imaginary friend who uses drugs to bring himself into reality. He has constructed a complete life including a wife and son in the real world, but is dependent on pills to maintain their existence. It’s a twisted reversal of the role of drugs, and one that allows for characters, settings, and all of reality to be altered on a whim. There’s plenty of promise in Neverboy #1, but the results are underwhelming.

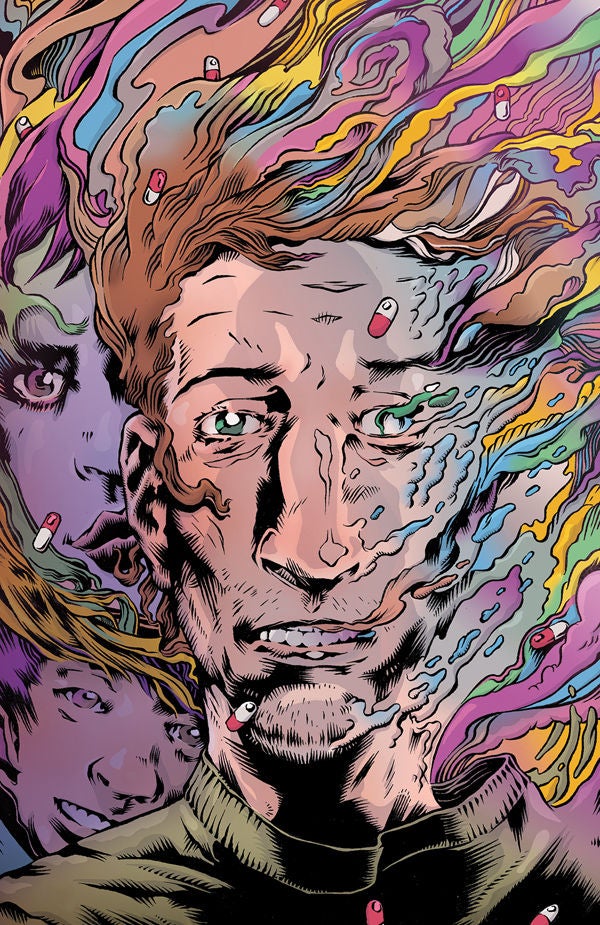

The cover by Conor Nolan reveals a wild dichotomy between reality and imagination with Neverboy’s face streaming away like rainbow tears unrestrained by gravity. Nothing like that imagery is executed within the pages of the issue. The storytelling is very direct with no sense of experimentation and limited alterations to the basic appearance of the real world. Only at the end of the issue does anything as bizarre as the concept or cover arise, and its execution is unimaginative at best.

Jenkins does include oddities that will reward observant readers. The transformation of an abandoned store in the background into a cafe or the slow discoloration of Neverboy’s hair all build toward the climax of Neverboy #1 and conceit of the series. There is an exaggerated appearance to Neverboy and another imaginary friend that briefly appears, but it never feels as though Jenkins is pushing himself to provide noteworthy work.

Most of the art is serviceable, but there are panels that distract from the flow of the story. Character’s faces often lack structure. There are several instances where heads appear to be flattened ovals with a face drawn across them. Several transitions lack a natural connection as well, leaving readers to question exactly what they are looking at and why. When Neverboy looks at someone else’s emergency room paperwork, the next panel is a close up of a list. It is supposed to be Neverboy’s writing on his own form, but the line of sight drawn in the former panel connects it to the stranger. It’s an ambiguous and unnecessary juxtaposition of panels that could be easily clarified.

Neverboy himself possesses about as much depth as an imaginary friend. His concerns and desires are all easily discovered on a surface level. It’s never hard to discern his motivation because there is never any ambiguity or conflict as to what he wants. That isn’t necessarily a problem, but it’s clear that Simon wants Neverboy to appear more complex than he does here. Simon opts to provide a gut wrenching revelation about Neverboy’s past in the middle of an action sequence. The four-panel flashback is very effective, but its placement is tonally jarring.

Neverboy #1 does not lack for potential. It alludes to The Odyssey, flirts with psychedelia, and packs plenty of pathos. However, none of that promise is ever realized. Instead, the story is told in a the most direct manner possible, failing to challenge or inspire either its creators or readership.

Grade: C–