Seeing Jurassic Park in theaters is my very first memory – well, not the actual viewing experience, but the drive home from the theater. Only three years old, I unbuckled myself and crawled into the back of my parent’s suburban as they drove. They didn’t realize what I’d done until I began to shine a flashlight out the back window and scream, “Go faster! The T-Rex is coming!” They were horrified to say the least, but the only emotion I can recall is the pure joy I felt after seeing Jurassic Park. It expanded my imagination and ensured a love affair with movies and stories that will never end.

Videos by ComicBook.com

I wasn’t the only person to have this sort of reaction to Jurassic Park during the summer of 1993. Steven Spielberg’s movie made more than $900 million dollars in theaters during its initial run, a figure that would not be topped until four years later when Titanic became the first film to ever breach $1 billion. It also spawned an enormous marketing campaign and three theatrical sequels to varying degrees of success.

Jurassic Park was re-released to theaters for its 20th anniversary two years ago. I worried that returning to this milestone motion picture on the big screen would diminish my memories and leave me disappointed. I was suddenly an adult and a novice student of film whose taste had changed rapidly in the past 2 years, let alone 20. Then I watched it again and… it totally holds up. Despite facing two decades of advancing CGI, budgets, and directorial techniques, Jurassic Park is still a highwater mark in the realm of blockbuster movies.

Now, instead of making myself a dangerous highway hazard, I’m more interested in asking a single question: Why? Why is Jurassic Park one of the best blockbusters to ever hit the silver screen?

Less is More

Close your eyes and think about the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park for a moment. Think about all of the different ones you see, the chases, the hunts, and the peaceful connections. Now ask yourself how much screen time do dinosaurs take up in Jurassic Park.

The answer is actually 14 minutes, and that’s out of a 127 minute film.

Spielberg took a quality over quantity approach to showing the dinosaurs and utilizing set pieces in Jurassic Park. Rather than shove as many ancient reptiles down the audience’s throat as possible, he carefully planned and crafted each appearance for maximum impact. There’s not a single appearance of dinosaurs in the film that can be considered forgettable.

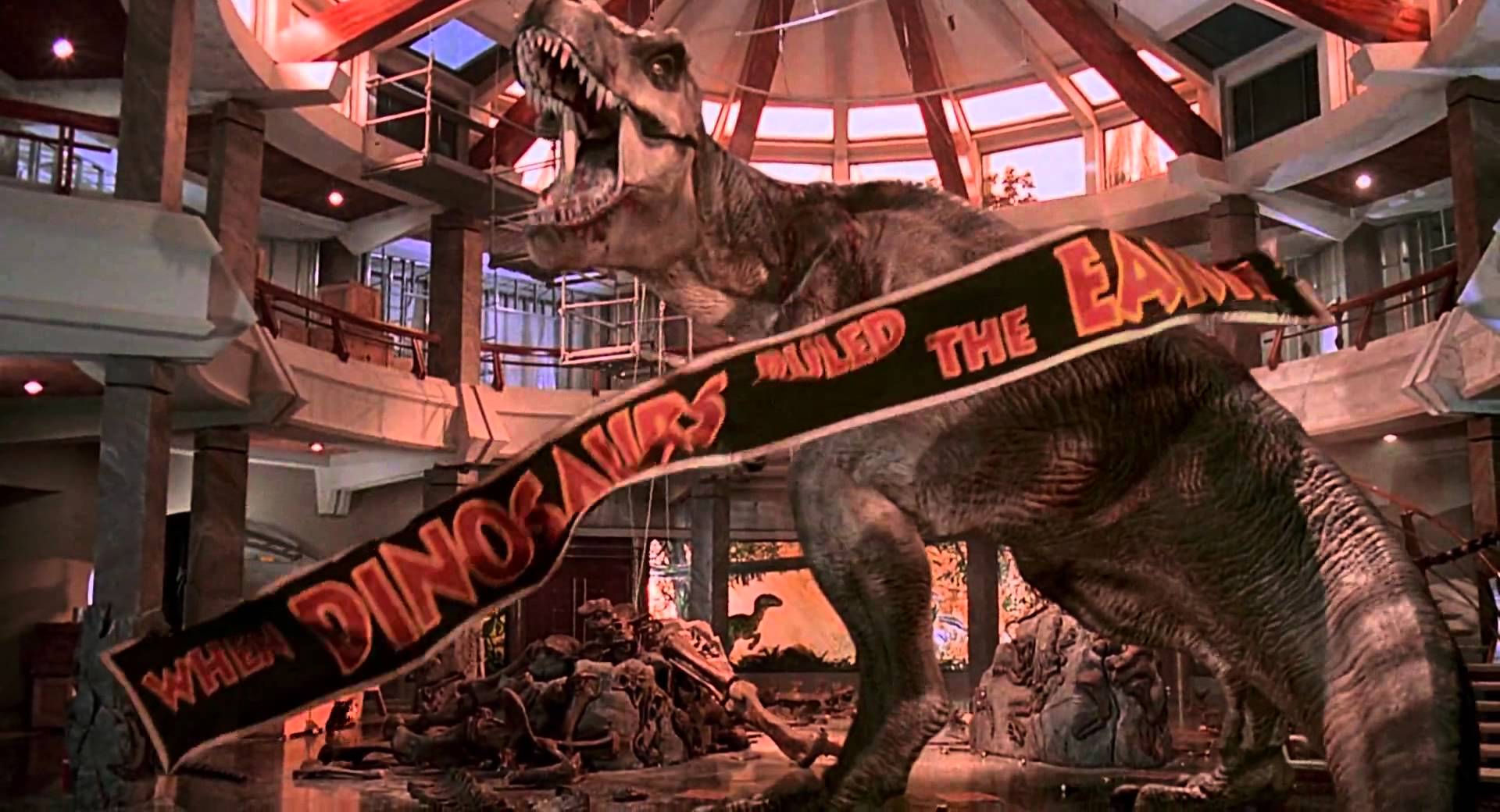

Consider the T-Rex, the fearsome centerpiece of the film. She appears in only four scenes, two of which are barely separated. Yet every time she appears, the action is jaw dropping. Everything about her first appearance is incredibly tense. Whether it’s eating Gennaro, flipping the Jeep to get at the children, or dashing Ian Malcolm into a bathroom, each moment absolutely sings. Even years after seeing the movie, it’s easy to recall complete sequences. This speaks to Spielberg’s mastery as a filmmaker too. Very few can compete with him when it comes to directing action, and Spielberg is functioning at the top of his game here. The end result is that the few minutes the T-Rex spends on screen leaves a remarkable impression.

Spielberg doesn’t rely purely on chases and bloodshed to awe viewers. There is no more iconic shot in all of Jurassic Park than the initial pan of the valley that reveals Brachiosaurus and Parasaurolophus herds. The scope and majesty of this reveal isn’t based on the graphics alone, but the perfect presentation as well. That same wonder-inducing spectacle arrives on a micro-level later in the film when Dr. Grant and the kids are able to feed a single Brachiosaurus from the treetops. To continue to bombard audiences with endless shots of dinosaur-filled valleys would only rob this revelatory moment of its impact. Spielberg knows this and lets the big moments of Jurassic Park stand without competition, which is why they all feel like big moments.

Practical Effects

Of those 14 minutes of dinosaurs, only 6 involved the use of CGI. Whenever possible Spielberg relied on practical effect rather than digital ones. This decision stemmed from personal experience (his previous blockbusters like Jaws and E.T. were shot with no CGI), practicality (those 6 minutes took upwards of six months to fully render), and an understanding of the value of practical effects.

Practical effects not only look more real because they are literally real, but they better engage environments and actors. In a purely CGI rendered scene, actors are left in a blue or green sound stage with only one another to respond to. Using models and animatronics, allowed the cast of Jurassic Park to play off both the lush jungles of Maui and the horrifying visages of resurrected carnivores. It’s much easier to respond to a T-Rex when you can see it’s enormous jaws opening before you.

This also led to some happy accidents. When the T-Rex is attacking Lex and Tim, the glass above their heads was never supposed to move. Unfortunately the animatronic head applied to much pressure and launched both itself and the plate glass forward. The resulting scene is unforgettable with the two children screaming and pushing with all their might against the T-Rex. It’s a scary accident, but the movie is better for it.

By only relying on CGI when absolutely necessary, Spielberg avoided breaking the spell of the film. Like an experienced tailor he knows how to create the least number of seams, and understands the importance of hiding each of them. These ideas have been proven time-and-again in the subsequent decades, often by Spielberg’s peers. The effects used in George Lucas’ Star Wars prequel trilogy were far more advanced than what Spielberg was able to use. But if you watch these films side-by-side, only one of them regularly gives the impression of being fake when CGI is in use. Whereas Spielberg blended the fantastic with reality, Lucas opted to invent a new reality and it has not aged well. George Miller on the other hand took Spielberg’s approach on Mad Max: Fury Road, opting to only use CGI when practical effects proved impossible. The result is the most breathtaking blockbuster of 2015.

Masterful Storytelling

Steven Spielberg, the name that keeps arising in this dissection is the main reason that Jurassic Park is a classic blockbuster though. The focus on quality over quantity and utilization of practical effects weren’t flukes, they were a purposeful decision made by a master storyteller. They were choices made in order to create the best possible movie going experience by one of the best directors of the 20th and 21st Centuries.

It’s not just the specific use (or lack thereof) of CGI that has been ignored by so many subsequent movies in similar veins. Jurassic Park also utilizes invigorating action sequences with a chase that stacks up to be almost as good as Spielberg’s greatest in Raiders of the Lost Arc. The horror – just think of Ray Arnold’s severed arm falling on Dr. Sattler’s shoulder – can be every bit as scary as some of the biggest jumps in Jaws. The suspense in the kitchen as the velociraptors stalk the children is unparalleled.

And at the center of it all is a group of characters and a story that are well-worth exploring. All of the central heroes are fully formed when they walk onto the screen. You know exactly who Dr. Ian Malcolm and Dr. Alan Grant are within a few minutes, and exactly why they will not get along. Even smaller roles like the unfortunate Mr. Arnold and big game hunter Robert Muldoon are clearly characterized. These representations form the emotional core to Jurassic Park that lends all of the big budget effects actual substance.

That’s the reason Jurassic Park is a classic. Not because it did something first, but because it is a good story incredibly well told. That’s why more than twenty years later I still love Jurassic Park. It’s the sort of movie that can make almost anyone fall in love with big, blockbuster cinema. So I’m every bit as grateful for the experience I have watching the film now as I did when I was three years old.

I’m also still grateful that my parents let me escape from that ride home largely unscathed.