When done right, real world settings can do far more than just improve a story. They can become characters in their own right. Whether in works of literature (Los Angeles in L.A. Confidential), television (Baltimore in The Wire), or comics (New York City throughout the entire Marvel Comics line), some stories are bound to the world in which they are imagined. They derive a fully realized sense of place that delivers endless riches to those telling the story. In these stories, the ones where a city truly comes alive, it’s not a simple matter of knowing maps and history. It becomes a dedication to the scenery that requires experience and intensive knowledge; the kind of awareness that can only come from a mastery of both the landscape and the medium through which it is being conveyed. This sort of work isn’t common, but it has the ability to transport readers through a screen or a page.

Such is the case with Wayward, where artist Steve Cummings and writer Jim Zub transport readers to modern-day Tokyo. Wayward follows Rori Lane, a half-Irish and half-Japanese high school student who has just relocated from Ireland to live with her mother in Tokyo. There, she not only discovers that she has mystical powers, but that she lives amongst figures from Japanese folklore. As of Wayward #6, the entire story has taken place within Tokyo, a city that is composed of more than 13 million people and is one of the 20 largest cities in the world.

Videos by ComicBook.com

Both Cummings and Zub have extensive experience with Japanese culture and the city of Tokyo itself. Zub first grew interested in Japan through exposure to manga and anime in high school. His brother was at university with many Japanese students, and he brought his new interest in the culture and stories home with him over Thanksgiving. Zub says that his initial interest in manga “Soon branched out into a greater appreciation of Japanese history and culture” and “working on Wayward has given me even more reason to dig into and appreciate that history and lore.” But his love of immersive settings began well before that point. He grew up a fan of Marvel Comics and “loved the idea that the Marvel Universe was this giant living space with dozens of characters on adventures across multiple titles.”

Zub’s love of Japanese folklore is clear in every script of Wayward. It is a well-researched tapestry of monsters, magic, and myths that is still far from being fully revealed. Each issue incorporates backmatter written by translator Zack Davisson in order to better explore the story’s elements. Davisson also contributes to the scripting process with notes concerning Japanese history and culture. However, the setting stems directly from Cumming’s involvement on the series.

“Right from the start when we first talked about working together on a creator-owned series, Steve made it clear that he wanted to set it in Tokyo and that the city should be a ‘character’ in the story,” Zub says.

It is up to Cummings to create a sense of place, bringing Tokyo life through his eyes and art. This may seem like an enormous responsibility, but it is one that Cummings is well prepared for as a longtime Japanese occupant. He and his wife both live in a suburb of Tokyo, and Cummings says that the city “has always been a place I have wanted to set a story in.”

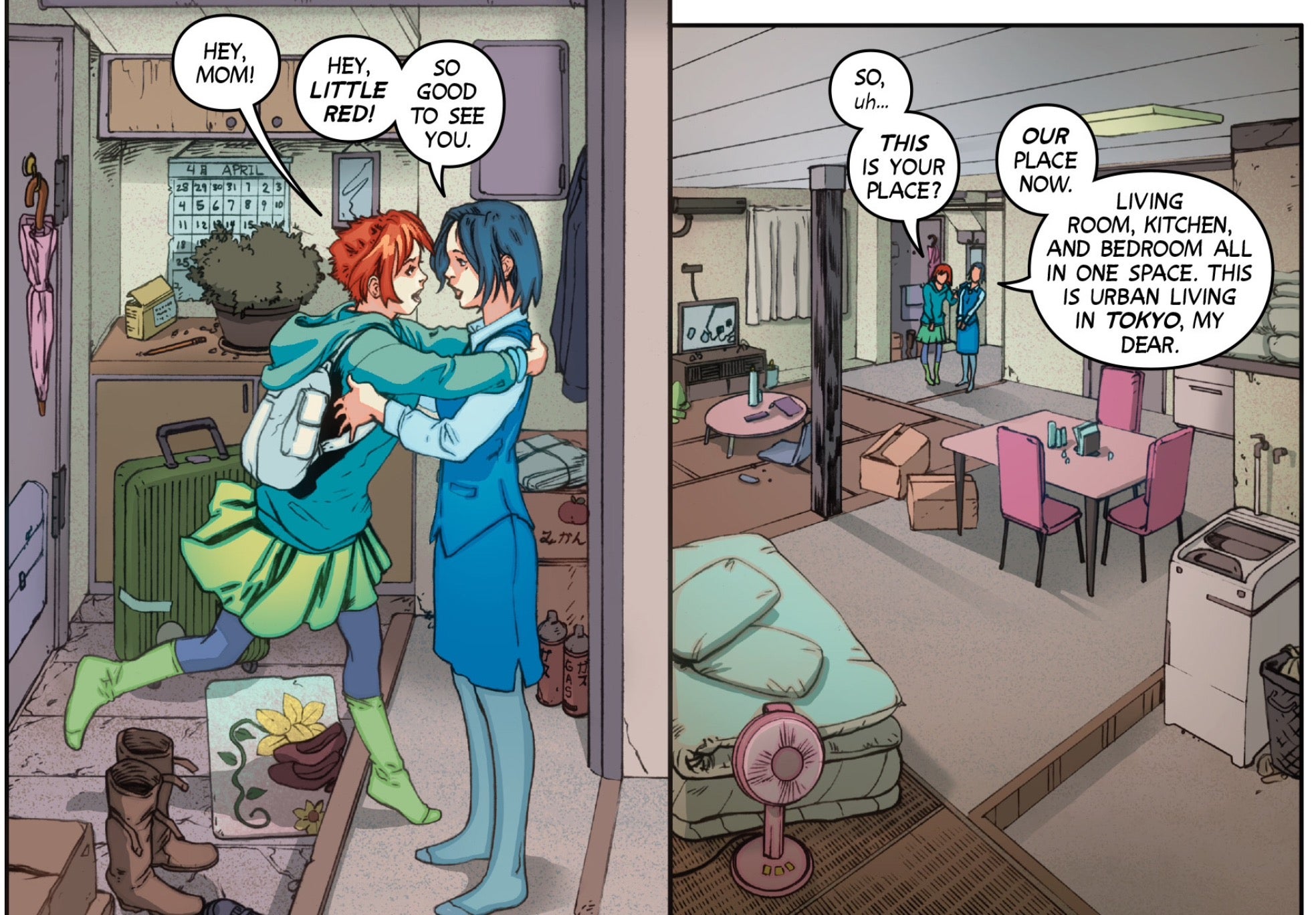

As an American and someone who has built a life in Japan for many years, Cummings can tell an audience what makes living in Tokyo such a unique experience. “The everyday normal aspects of life are things I really like to draw. They take a unique flavor when compared with similar things from back home in America,” says Cummings. Those details arise in the variety of settings found in even just the first few issues of Wayward. As Rori moves between her mother’s small apartment to a restaurant to her school, differences are clarified in details.

When Rori arrives home for the first time, there is no big show of cultural differences. Instead, those distinctions are found in the backgrounds and small changes. Rori leaves her shoes on a concrete entryway known as a genkan when she enters the apartment, which is shown to be a much more open design than most American interiors. A table in the living room is so low to the ground that the chair next to it does not even require legs. The elements in the first two panels alone could be cataloged and detailed, but they are not obtrusive. It is a genuine recreation of a modern apartment in Tokyo.

This is the reality that Cummings is interested in depicting. “That is the area that I wanted to show,” he said. “The normality that doesn’t exist as gleaming business centers but rather as sleepy neighborhoods that, to me, is the heart of modern Japan.”

Cummings recognizes the challenges of bringing such an enormous and varied city to life. Many American and Japanese comics have set their stories in Tokyo, and yet Cummings feels that “They (i.e. other American comics creators) never quite got it right, and only brush the surface of the city by showing the more modern areas set around the bigger stations. But those places are normally transit points, and not where people actually live their lives.” That’s a point Zub agrees upon, saying “We wanted to make it clear our story wasn’t about just showing tourist destinations and the expected, but a broader look at the many different parts of Tokyo.”

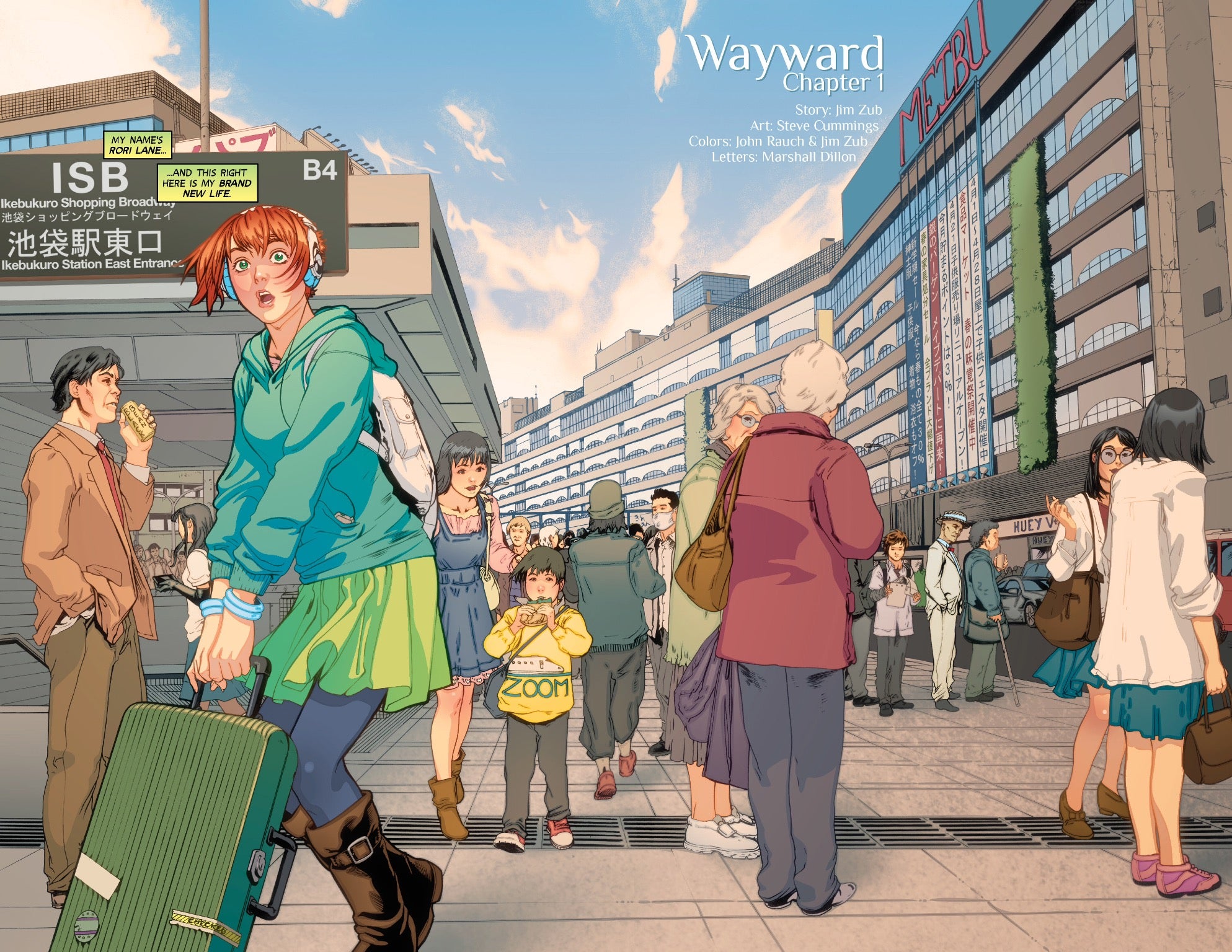

Their urge to avoid obvious landmarks is made clear in Wayward #1’s introductory spread when Rori arrives at the Ikebukuro Station. Although Ikebukuro is a station that any Tokyo native would recognize, it is far from the well-worn wonderlands that are Shibuya and Shinjuku. Ikebukuro is a place not far from neighborhoods and schools, one that a young woman might easily find herself living in. The spread presents a new side of the city as Wayward’s first expansive establishing shot.

But not all of Wayward’s locations are based upon specific settings. Cummings says that some are only “meant to exemplify the overall look and feel of a particular area of the city.” However, this spread is set in a very specific locale. It is intensely detailed with a long stretch of buildings, each with a distinctive appearance, a fully populated plaza. There’s even distinctive kanji (logographic characters used as part of the modern Japanese writing system) along seven hanging banners. The drawing is so well realized, it looks like Cummings drew it while sitting on park bench at Ikebukuro Station. That accuracy may come from Cummings’ method of collecting reference material.

“Establishing shots and backgrounds all depend on lots of reference,” he says. “Lots of photos taken at high resolution from as many angles as I can manage is the way to go. My phone’s camera is set for 13 megapixels, so I can get the best and clearest level of detail. I try to add as much of the detail that is available to each shot to make it really come alive.”

It’s difficult to tell how close to reality this depiction is without having traveled to Ikebukuro or, at least, possessing a photograph. Luckily, I had the opportunity to visit Ikebukuro while in Japan recently. When I walked into the plaza, I expected some resemblance, but was blown away by how familiar this new place already felt.

Photograph by Alexandra Janky

Cummings’ depiction of Ikebukuro is unmistakable. It is not perfectly photographic, but the look and feel of the location is captured perfectly. Standing in the same spot as Rori, it’s easy to relate to her rush of anxiety with long rows of buildings mounted on all sides of you. Even the colors by John Rauch and Zub are clearly related to reality. On a sunny day with nothing but blue sky above, buildings and greenery all stand out in appropriate shades. Being there or–hopefully–by looking at this photograph, it’s easy to see that Cummings’ locale is not just based on Ikebukuro, but realizes the actual experience of being there.

Each of Cummings’ adjustments between reality and his artwork is purposeful in nature. The two most obvious differences are the addition of a sign, and the alteration of the buildings’ depth and angle on the right side of the page. The sign helps provide a natural expository caption, placing Rori at a specific locale. The change in the buildings adds an additional perspective in order to create a better sense of what Rori is feeling. She is overwhelmed by the world around her, reflecting a mix of fear and astonishment at this enormous, new city. Cummings’ restructured buildings deepen the panel and make the world seem even larger to readers. If you were to move the camera ten feet to the right, then you would capture these additional buildings in just as lifelike of a fashion. This alteration may not be true to reality, but affects the truth of what it feels like to stand in the middle of Ikebukuro. Having stood there myself as a new visitor to Japan, the overwhelming size of the city is something I can appreciate. While I was much more awestruck than fearful, I can sympathize with that reaction as well coming from a young person on their own.

All of these are examples from Wayward #1 alone. With each subsequent issue, Cummings and Zub have continued to build Rori’s world and enhance their depiction of Tokyo. The story has continued to focus on neighborhoods, office buildings, and schools presenting the experience of the city from an insider’s perspective. The details and depth found in the artwork add more and more valuable information about Rori’s journey in her new country. Tokyo enhances both that story and the experience of discovering a city on the opposite side of the world

From the very first panel where Rori drew the kanji for Japan in condensation on her window, it was clear that this story was as much about a place as anything else. Through the pencils and words of Cummings and Zub, they are bringing that place to life for American comic book readers each month.

Special thanks to both Steve Cummings and Jim Zub for answering questions and providing insight into the process of creating Wayward.