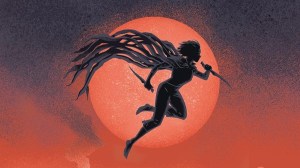

The third and final issue of Suicide Squad: Blaze arrives this week and given the series to date, it’s not a spoiler to say that this title is killing it — literally — when it comes to heroes within the DC Universe. The title has, over three issues, taken on not just the Squad, but the idea of heroes in a way that is deeply original and rooted in a sort of realistic horror that pushes boundaries and prompts some major questions about, well, everything. And it does it all while being absolutely crazy and unexpected.

Videos by ComicBook.com

With the Suicide Squad taking on a strange alien threat that has cut its way through DC’s most powerful heroes and leading up to just a few lackluster recruits as the last line for humanity, Suicide Squad: Blaze #3 wraps things up with some truly unexpected and surprisingly human moments amidst twisted violence and unexpected horror. ComicBook.com recently had the opportunity to chat with both writer Si Spurrier and artist Aaron Campbell about the final issue of the series, how far they were able to push things with the series, what they hope people take from the series, and a lot of really interesting details about the series overall.

Boundaries

ComicBook.com: Suicide Squad: Blaze seriously upends expectations on how DC tends to treat its iconic characters and that extends to the Suicide Squad mainstays. How much freedom were you given with this title and what were the boundaries in what you could do with Black Label that you found when developing Suicide Squad: Blaze?

Spurrier: I think the purest beauty of working for Black Label is exactly that, there are almost no boundaries. That’s the great appeal. It’s the great joy. It’s combining these two wonderful things of having the same freedom you might expect to get from a creator own title, while also being able to work with characters that are recognizable, characters that we grew up with, characters that come with a lot of affection attached to them.

There are some practical boundaries. There’s the sort of granular stuff, like it really doesn’t make good sense to be including A-list DC characters in the same panel as appalling misuse of language or really visual acts. But that didn’t stop us from being able to involve the A-list characters like the Justice League in some really shocking moments and indeed suffering some quite shocking fates.

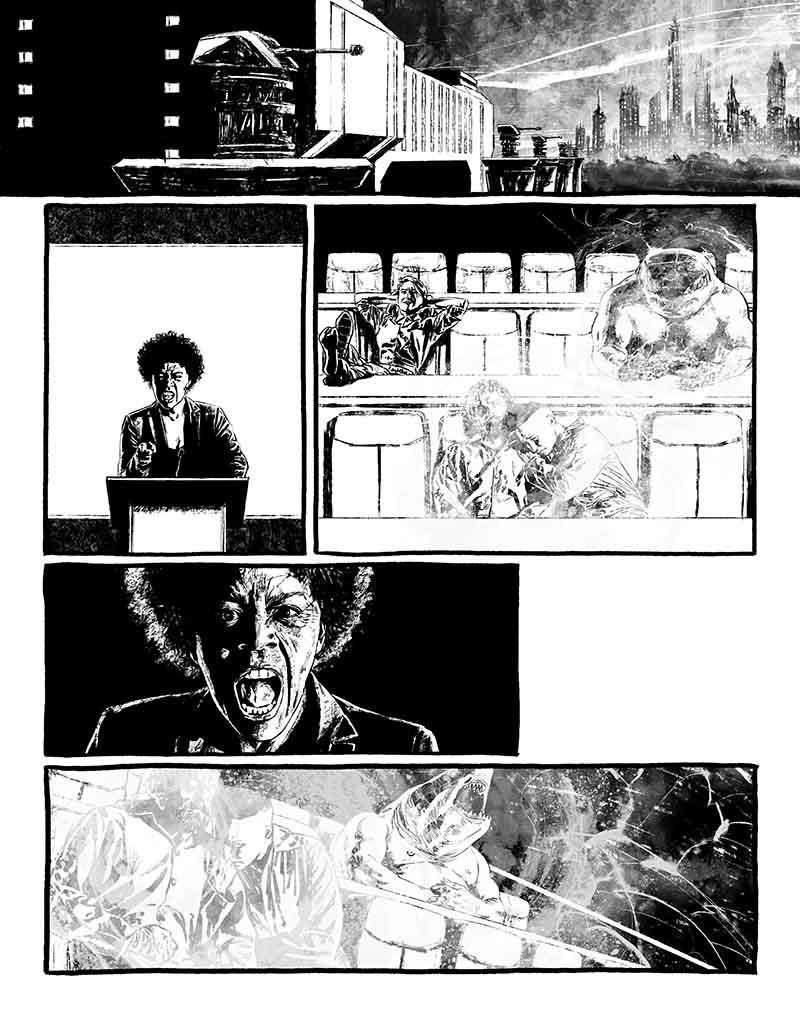

There was a self-imposed boundary in the sense that we came into the project with this interesting challenge to ourselves. We knew that after many, many years of reading Suicide Squad stories, readers are cynical enough now to know that there’s really not much chance of the recognizable squad members, Harley, Rick Flag, Peacemaker, King Shark, and so on whatever the current iteration is, there’s not really much chance of those characters actually dying in the main comic. It’s called Suicide Squad, and yet there’s relatively little actual death among the members of the team. So, we came into this book sort of expecting the same to be the case, even though it’s a Black Label book, we wanted it to feel like it could be happening in a recognizable version of the DCU. And so, we didn’t imagine that we would be killing all these recognizable characters.

That in fact is exactly why we came up with this solution of focusing instead on a bunch of rookie characters who are brought in, who are considerably more doomed, who are, I think, considerably more relatable, because they’re not characters who’ve been in sort of spandex circles their whole lives. And hence it’s far more heightened stakes when we see them in action. So that was our reason for doing that.

But then halfway through putting together the first issue we realized, you know what, fuck it, we can do both of these things. We can present these fascinating new characters whose safety is absolutely not guaranteed, and then just when our readers think that the main veterans of the squad, the recognizable spandex-y characters are probably safe, we can start killing them too. And that’s exactly what we did. So yeah, it’s sort of just this slow escalation where nothing is quite as sacred as the readers probably thought it was when they started reading it, right up to that ghastly last moment when you realize that the world itself is in fact all up for grabs.

Heart of the story

One of the things that I find interesting, I find this interesting about art in general, there’s always some sort of meaning or meaning is sometimes not even the right term. Sometimes it’s about, you’re just going to think about things after. You may not have this specific meaning, but you’re definitely going to be thinking when you come away from it. I think Suicide Squad: Blaze is one of those things especially as we get more into the true darkness of Amanda Waller and, by extension, the greater organization she’s involved with and the government … Is there anything that you hope that people take away from this and be an actual message you want them to think about, or just what intellectual thought process you hope they have with this book?

Campbell: I think at the core of the story is the notion that empathy is absolutely necessary in order to create a healthy, loving society and community. Without empathy, you end up with what we have in Suicide Squad: terror. I listen to a lot of true crime podcasts, and the common refrain always is terrible upbringing is not an excuse for the terrible things you do. And that’s true. But our creature that we created is slightly different from most of those individuals because he was completely removed from anything human.

There’s an actual story. I’m not sure if Si and I ever talked about this. There’s a story from history about a king, and I think it was a king in Egypt or a king maybe in Mesopotamia. I think it was related in maybe Herodotus. I’m not sure. The basic story goes that this king was trying to figure out if humanity is something that we’re born with or something that we learn. So, what he did is he took some children, or it might have just been one child, but he took at least one child, and from the moment they were born removed them from human connection. Kept them in a room, fed them, that’s it. They weren’t taught language. They weren’t taught anything. As the story goes, the child basically turned into a raving beast.

It’s a horrifying story, and the idea that anyone would ever actually do that, whether or not there’s any truth to that story is probably up for debate. It’s probably apocryphal. Who knows? But it’s part of that moral that we need touch. We need connection. We need love. We need all of that in order to become healthy adults who are positive, contributing members of the community that we all share. So that’s it. That’s really, I think, the heart of the story.

Writing 101

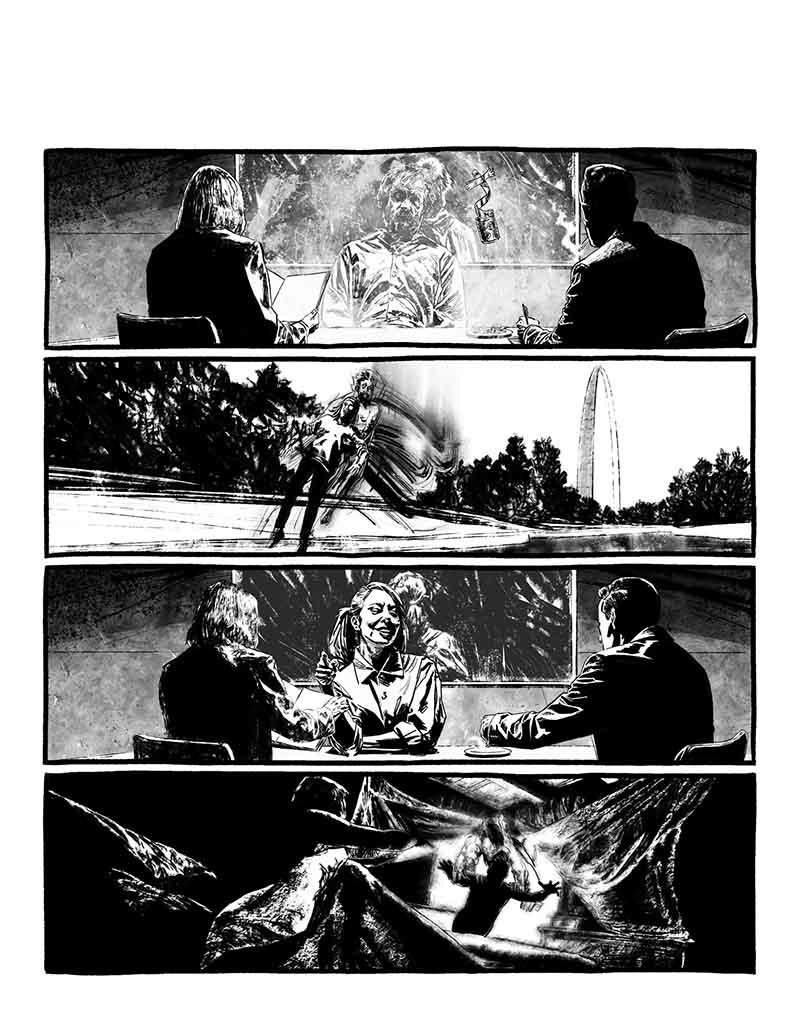

Something that struck me about the series as a whole, but particularly the last issue, is that at its root, there’s a lot about humanity here, both good and awful. There are no heroes here, but I also didn’t walk away feeling totally dark. How did you balance this brutally honest and also really cynical aspect of things with what felt like genuine moments of understanding and even hopefulness? Taya’s whole story evolution in particular is seared into my brain.

Spurrier: I think this is really just a product of writing 101. You have to be able to present juxtaposing levels of stakes. You have to be able to find relatable human beauty in the midst of otherwise tragic things. A story isn’t generally speaking satisfying, unless it presents some form of positive outcome. And that’s true of a great tragedy. Hamlet, everybody goddamn dies, but you still come away from it having felt something, learnt something, even something a little positive about the ways that people ought to be, as opposed to the ways that people often are. So, in this case, I’ve just described in the first answer, this escalating series of stakes, the fact that everything is expendable, nothing is safe. And yet against this backdrop of epic level violence and deconstructive superhero analysis, the only way you can redeem this story is to make it about the way people feel.

And all the way through we have assumed that it’s Mike’s story, the main character, and about a couple of pages right before the end of the second issue, maybe we started to realize that we’ve been backing the wrong horse. The guy is actually toxic. He’s a parasite by his own admission. And the person whom up to that point we had assumed was the toxic one, Taya, is actually this tragic character who loses all her identity in the face of there not being any danger, in the face of mortality, the certainty of her impending death. She becomes this clingy, co-dependent person who is so totally alien from the person that she was before. So, this last part is all about untangling that knot, bringing Taya back to a point that she discovers something of her own spark, something of the fire that defined her before she stumbled into this hideous situation.

But also, kind of redeeming Mike and I say kind of, because at no point does he cease to be a toxic parasite. It’s just that he knows it and self-knowledge goes a long way, nosce te ipsum and all that, up to the point that his self-knowledge, his awareness of his own awfulness is sort of the thing that saves the day, if that’s how you want to see the way the story ends.

Anyway, to your point, all of this is elaborately tied into humanity, and it’s messy and it’s not neat and tidy. It doesn’t happen like it does in a blockbuster where everything is all neat and tied up and we cut away just when things start to unravel. We are very much there for the unraveling and it’s brutal, but I think that’s probably more valuable than the alternative. And I think it’s something that we as creators, especially in this funny little sub-genre of the superhero, we should do far more often, we should be braver about showing how messy this stuff is.

Faces

I wondered if you could talk about your evolution in drawing the characters, especially Mike, because I know when we talked initially, you talked about how he’s arm-fall-off boy but more pathetic and pitiful in terms of some of your inspiration for it. But as we see him become perhaps a little less pathetic, his face kind of changes a little bit, even though he’s still not the best character. Talk to me about the faces.

Campbell: Well, I mean, with Mike, especially… Well, it’s interesting because I shoot photo reference for everything that I do. I hire models, and I actually worked with real actors. So, a lot of the inspiration and the source of where a lot of the characterization comes from is the work I do with those actors. It was interesting because the person I was working with for Mike got hired onto a gig where he had to start growing mutton chops. So, between Issue 1 and Issue 2, he suddenly had a mustache. At first, I was like, “Ah, crap, I’m going to have to draw that mustache out.” But then I started to think, “No, actually, this is something that I could work with in terms of the evolution of Mike as a character,” the idea that he’s becoming more confident issue by issue, and that’s represented in his outward look.

Then what came to mind as I was working through Issue 2… because Si made this comment, he was like, “Oh, man. Mike is starting to kind of look like the killer a bit.” I was like, “That’s interesting. I’m going to lean into that even more.” Then by Issue 3, he’s got a full beard. His hair is just a mess. So, the outward confidence of Mike is also starting to mirror the insanity of the killer himself, like that sense of overconfidence, which can be poisonous to anyone. That’s sort of how I started to approach Mike.

Of course, for Tanya, Tanya was on the opposite trajectory, and she was losing her confidence. I remember early on talking to Si. We were trying to figure out who these characters were. I think I’m the one that suggested, “What if Tanya… what if the core of her character is her chaos, is that uncertainty, the thrill that comes with the insanity of her life?” She’s always living on the edge, and that’s what gives her confidence. It’s what gives her her drive. When suddenly she’s invulnerable and can’t die, that spark disappears or starts to disappear, and that’s when she starts to lose her sense of self and ceases to really understand who she is anymore if she can’t live on razor’s edge. Then the way that I started to approach Tanya as we went is just this tragically, lost, deeply morose person desperate to recapture any of her former spark.

That’s how I approached it for each of those characters. Then you can kind of extrapolate that into the way that I thought about all of the characters. Whatever book I’m working on, I try to really get into the head of the characters, like the way that a director or even actors in a production would. It just gives me a better sense of where we’re going. Because I think the way that I use emotion is so integral to my style, which has become more and more apparent as people comment on it more, and the more that they realize that the more it makes me reflect on what I’m doing.

Mike

One of the things that stuck with me is that the first issue of this series saw, for lack of a better description, kind of kicking Mike while he was down. When we talked last, we talked about his weird invisible arms. In the end, Mike kind of transforms. He’s simultaneously both less pitiful and more pitiful. Why in a sense center this around his journey?

Spurrier: Simply because there is nothing more compelling than a flawed person. Everybody in this story is a flawed person. So, we’ve sort of gravitated to the most flawed person and only revealed the true extent of his flaws by drip feeding them little by little. Almost every character that I’ve ever written that I’ve fallen in love with, has been an accidental monster. And the ones that I really relish are the ones who know that they are monsters, but can’t quite stop for whatever reason, either because they have to be a monster or because they simply can’t bring themselves to stop or whatever it is. That’s very true of Mike. It’s gratifying and a little manipulative and mischievous to put readers in a position of rooting for a bastard, because it forces us to acknowledge that the world, we live in is not a binary place where everybody is either good or bad.

Nobody truly imagines themselves to be evil. Everybody who does bad things, considers it to be the circumstance or the product of some prior event. Nobody ever sets out to be an evil person. Just like frankly, everybody thinks that they are good deep down. To reveal how utterly arbitrary that is and how pathetic it is to claim that anybody working against you is therefore evil, is I think, a really important lesson, because if we all realized that we are just muddling through, trying to find the right morality to make the greatest number of people, the most happy they can be, for the most amount of time. If we all thought like that, rather than dehumanizing and othering, then we’d probably be all a lot better off.

Now that’s an awful lot of big nonsense and profound nonsense to be waffling about in an interview about a superhero story, but you know what? It’s there. It is absolutely part of the driving thesis whenever I write superheroes, that the real heroic stuff is not being done by people in capes punching holes in things. It’s being done by the emotional decisions that they make, by the supportive things that the people around them make, and by the aspirational choices of the ordinary people who are watching them. And that is never more true than in something like Suicide Squad.

The worst horror there is.

For me as a reader, while there are a lot of horror elements to this, and I love horror, what really chilled me is that it felt in the end like we are the monsters. That’s less of a question and more of a statement, but I’d be interested to hear your thoughts on that takeaway.

Spurrier: I think that I have already waffled about this in the earlier answers. To add, well, there’s two things. One is that when we talk about genre, I start to get itchy anyway, because I happen to believe that genre is totally unfit for purpose. We utilize these arbitrary little terms to define what a story is, and they don’t even describe the same sorts of stuff. You know, horror, Western, romance, comedy, that’s what, four or five different terms, one of them’s an emotion, one of them’s a time period, one of them’s a location, but these things don’t make any sense. You end up describing any story as a period, comedy, crime, science fiction, Western, and that’s a ridiculous mouthful, but it’s true of whatever story we’re describing.

I say this because when people talk about horror, it makes me sort of cringe a little, because horror’s just one outcome. People tend to think of horror as being a sort of conspiracy thriller arc in which the stakes perpetually rise until the point that you achieve some sort of revelation of horror, it’s seeing the monster, or what have you. Generally speaking, at which point the whole thing falls apart anyway. My idea of horror is simply a story that gets under your skin and stays with you and gently horrify you. And if that can be achieved by giving people something valuable to be horrified by, rather than just shock and shlock, then so much the better.

So yeah, the overarching answer here is that we are the monsters. Everybody’s a monster, everybody’s a hero. What truly horrifies is the way that people behave to each other. That’s more horrific than any boo moment or any scary psycho lurking through a windowpane. It’s not as snazzy and sexy to describe your book as a book about the dreadful things that people do to each other, but that’s genuinely the worst horror there is.

Batman

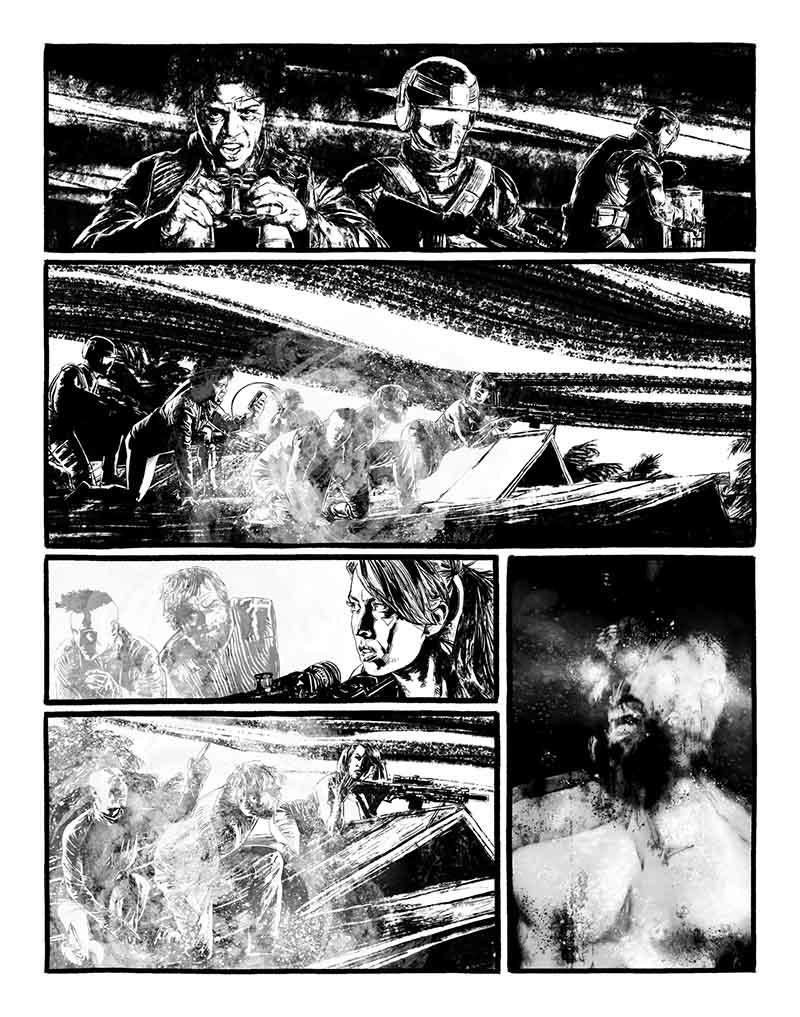

There is an absolutely freaking hilarious page where somebody comes back and they’re wearing… The dude’s in a shark head?

Campbell: Yeah, a plushy shark hat.

First, whose idea was this delightful piece of art? Second, walk me through the thought process of all the stuff that you put in there.

Campbell: Well, it was in the script, so when Si wrote it, he did say that he shows up and he’s standing there with the big, plushy, furry, fluffy shark hat on. They’ve obviously just been doing some role play, but there wasn’t a whole… It was also indicated in the script that basically the rest of him was naked completely. That’s all he was wearing. But that was kind of the most that Si had put into the script. So I was like, “Oh man, okay.” I mean, we’ll just say it. This is King Shark’s mom, so obviously she’s fetishized King Shark’s father and just sharkness in general. So her entire house in Hawaii is Tiki themed, shark everything.

So I just started thinking, “What are some funny things?” Originally, I think I had put in an actual set of a shark jaw. I think it was on a plaque that said something like “RIP Dad” or something. So it was the idea that was actually King Shark’s dad’s mouth on the wall beside it. I was like, “Yeah, it might be a little too far. What if we just got maybe some shark teeth and it said, ‘Baby’s first teeth’?” Then I was like, “What else could I do?” Then I was like, “Oh, man.” You know that classic T-shirt image of the three wolves howling at the moon?

I was like, “What if it was three sharks howling at the moon?” So I put that on a surfboard in the back. Then it was like, “Well, they’ve got to be having Tiki drinks.” Then I was like, “Well, the Tiki mug needs to have shark teeth, like a shark motif.” So just the idea was that everything I could do to make everything a shark thing. I don’t know if you pick up on this, but the character, which we’re not saying right now so we don’t completely spoil it, but the character has his underwear hanging off the front of the coffee table on the foreground. If you look closely, you can see the Batman symbols on him, so he’s wearing Batman underwear. He has a secret love of Batman and wears Batman underwear.

Easter Egg

Suicide Squad’s one of my favorite general rosters of characters, but I really love them because their stories kind of go in places that really do make you think about the state of the world and your own humanity. This one in particular, both visually from the art and the content of the story definitely, especially with the world being what it is, has really given me, just even outside of the professional aspect, as a reader so much to think about. I’m hoping a lot of people come away from it with that as well.

Campbell: Well, thank you so much. I will say this. There’s a little Easter egg that I put into Issue 1 that gets resolved in Issue 3. It’s something that even with a magnifying glass, you’d never be able to understand what it is you’re looking at. But in Issue 1, when the rookies get their powers, and we have that sequence where each one is basically demonstrating what they’ve got. We have Boris there, and he says something to the effect of like, “I can see the edges,” meaning he can actually see the edge of the panel border itself. But really what it meant was he can see the edge of reality. He’s pointing up to the corner of the panel. There’s a little crack up there in the corner of that panel. If you actually took a magnifying glass and looked, you could see there’s something inside that crack. What he is seeing is basically the final panel or not necessarily the final… In the last two pages of Issue 3 when we’re resolving everything, there’s this unfolding that happens, and that is what Boris is seeing through the cracks.

***

Suicide Squad: Blaze #3 is on sale now.