Videos by ComicBook.com

David S. Goyer, the screenwriter behind a number of comics properties ranging from the Blade and The Dark Knight trilogies to Man of Steel and NBC’s Constantine, is one of nerd culture’s most controversial celebrities.

That’s not without cause; he got fans up in arms earlier this year when he made joking remarks about She-Hulk that almost nobody found funny and, prior to that, made Man of Steel and then, in response to inquiries about fan reaction, told interviewers that he can’t possibly worry about fan reaction if he wants to make a good film.

Anytime a filmmaker says “I can’t listen to the fans,” it’s bound to land them in hot water but, in my heart of hearts, I actually think they’re usually right on the point. Goyer too.

If you listen to commenters on the Internet, it can and likely will be utterly paralyzing. It’s part of why as a policy anyone who writes about fandom on the Internet responds to a relatively small number of the comments; it can easily spin out of control and most of the people who are angry, frustrated or just spewing hate at you won’t change their mind anyway.

A serious issue with the perception of Goyer’s work is the same thing that arguably helped build him up as a filmmaker in the first place; with Blade, there wasn’t much public perception of the character outside of comics to go with, and so crafting a project that worried first about telling its own story and later, if at all, about what the audience response might be was hugely beneficial to the work. Add in the fact that most fans don’t have the kind of passionate connection to Blade that they have to other projects he’s worked on and you had a recipe for a project to be taken on its significant merits.

This approach served him well enough that it has informed everything that came after, as noted above, and that’s where he started to run into problems.

His work on the Dark Knight Trilogy drew detractors for a few reasons, but chief among them — at least among comic fans — is that he didn’t make the “real” Batman. The singularity of vision that he and Nolan had for the trilogy was often praised by critics but lambasted by those who were upset that Batman had let Ra’s al Ghul die, that he retired after too few missions, that the Rachel subplot was too intertwined with his whole identity, and other niggling complaints that ultimately boiled down to “It didn’t meet my expectations.”

Batman, though, is an elastic character. He was as responsible for The Joker’s death in 1989’s Batman as he was for Ra’s al Ghul’s, in many ways, and of course the fact that a number of The Joker’s nameless goons got likely got killed along the way never really registered a blip with most fans — just like the fates of League of Assassins members that weren’t making eye contact with the camera when they died in Batman Begins. From the Adam West TV series to the Tim Burton movies to Frank Miller’s noir-infused approach, fans are used to Batman being reinvented, and often going darker, angrier, more violent. That The Dark Knight was considered an unquestioned masterpiece likely helped deflect some criticism as well, and even many of the criticisms leveled at the films — like the praise — ended up in Nolan’s lap rather than Goyer’s.

But then we got to Man of Steel, and its depiction of Superman. The fan perception of the Last Son of Krypton is significantly less elastic, for a number of reasons.

First of all, while Batman ’66 took the Dark Knight so far in the direction of camp that a grim reinvention was a welcome change, Superman hasn’t really had that. His other-media depictions prior to Man of Steel have generally lined up, tonally speaking, even so much as to use the John Williams theme from Superman: The Movie in the series finale of Smallville. While the character has changed from time to time in the comics, it’s usually been incrementally — with the execption of John Byrne’s The Man of Steel, which is part of what may be at issue here.

Following the Crisis on Infinite Earths, DC reinvented Superman, powered him down somewhat, removed other Kryptonians from the DC Universe and a number of other tweaks that were aimed at making him more human and easier for readers to relate to. Writer/artist Byrne wrote the initial miniseries, reinventing Krypton from a world of supermen into a cold, sterile world driven by science in which mothers don’t even carry their children in the womb but grow them in a “birthing matrix.” Superman’s was attached to the rocket and blasted away to Earth at the moment of Krypton’s destruction.

In the post-Man of Steel era, there was no Superboy because Superman got his powers well after puberty. His power levels were significantly lower. He couldn’t breathe in space. There were no super-pets. In many ways, it was like a Christopher Nolan movie already: you take what you think works the most about the character and you put it into a more believable framework in a “real” version of our world.

What’s the point of all this? Well, Byrne’s approach had its detractors — and still does. Many of them vilified him at the time, and some still do. We have a few regular commenters here on the site who have utter loathing and contempt for the Byrne reboot and who will happily rant at us whenever we say something positive about the Superman comics of the ’80s and ’90s. Even Byrne’s universally-beloved work on X-Men and Fantastic Four is often called into some kind of question — “It’s overrated” — in order to justify a hatred for his Superman work that borders on maniacal.

It’s very much like what you see with many of Goyer’s detractors.

The execution of Zod — which was the focal point of so much outcry over Man of Steel — was inspired by a storyline by John Byrne which drew similar ire. Because of its proximity to when he left the title, there are even fans who believe DC hated the move so much they forced him out.

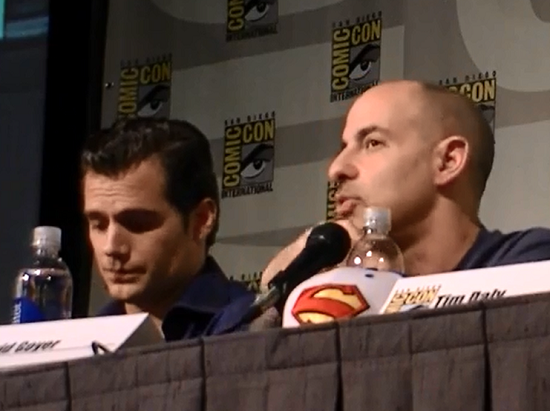

(This isn’t true; it was denied by both Jerry Ordway and Mike Carlin, who worked on the comics back then, during a panel on Superman in the ’90s at Comic Con International: San Diego in 2013.)

It doesn’t help that some of the most vocal detractors of Byrne’s Superman work were influential voices in the comics community. Mark Waid, for instance, has written a number of influential Superman stories, including Superman: Birthright, which partially inspired Man of Steel, and Kingdom Come, which many fans use as an example of why Superman should “never kill.”

This idea — that Superman is pure as the driven snow all the time — ironically embraces the same messianic concepts that Goyer was criticized for laying on so think Man of Steel. Perhaps that’s something he should have excised if he was going to adapt Byrne’s more “human” Superman.

But as with Byrne, touching the apparent third rail of reimagining Superman has turned Goyer into a hate figure for some fans. Now, when they dislike something about Constantine or worry about the quality of Batman V Superman, the first go-to argument is that “Goyer’s a hack.”

Goyer’s work is uneven — as is almost everyone in Hollywood. Things are done in large part by committee, and you have to be a special kind of famous or marketable to truly control every aspect of your project. Even then, you’ll sometimes get a bomb — sometimes one that was good and just didn’t connect with an audience, and sometimes the film is just not good.

Somehow — possibly because it’s fashionable to snark about Man of Steel at the moment — Goyer’s name has taken on a context akin to Michael Bay’s. Certain fans will complain about Goyer’s even theoretical involvement in a project, and celebrate his failures. In spite of the fact that even some of the film’s harshest critics praised the Kryptonian elements of Man of Steel, the comments thread filled up with bile when it was announced that Goyer was shopping around a TV series set on Krypton (it eventually landed at Syfy).

It’s this general sense that “he sucks, that’s why” that’s likely at fault for a lot of the frustration directed at Constantine, a show whose following simply can’t comprehend why a segment of the audience hates it. Changes had to be made to the source material ton suit the new medium, but…that’s what happens when you adapt to TV and film. It’s miles closer to Hellblazer than was the Constantine film, certainly, and it hews more to the “scripture” of DC Comics than does Gotham, for instance — or, heck, than Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. does to the adventures of whatever familiar characters appear on that show, even now that it’s a fan- and critical darling.

Goyer and showrunner Daniel Cerone fought to cast Matt Ryan, fought to dye his hair. They fought for smoking on the show and, in spite of having to make some concessions in just how and how often it’s depicted, they won. These are all things they did because they’re fans.

Many of those who have complained about Man of Steel are simply not fans of the John Byrne era — which was, as you’d expect, a big contributor to the source material of a film called Man of Steel. Goyer is. I am, for that matter, and so things like killing Zod in a spontaneous moment of saving human lives certainly felt less dark than Superman in an executioner’s hood, poisoning three Kryptonian war criminals with Kryptonite. That Byrne was a key touchstone for Goyer’s work was no surprise to anyone…and in case it was, he was open about it when defending himself after the film came out.

So…this is a guy who’s a fan, making films based on material he loved. He’s also contributed to some truly great material over the years, including The Dark Knight. It’s difficult even to mount a particular defense, since most of what’s leveled at Goyer is fairly surface-level stuff. If you don’t like his work, sure. That’s understandable. It’s difficult to understand the bitterness with which some fans talk about a guy who has been a major contributor to bringing comic book characters to a wider audience in a number of critically-acclaimed and fan-favorite adaptations.