Spawn #14 is one of the first comics I recall reading. My father took me to a local comic book store after seeing Spawn in theaters and I was instantly drawn to this issue’s cover with both Violator forms (the clown and demon) posed together laughing at some unknown dark joke. When you can still count your age on both hands, it’s easy to overlook the many flaws of that 1997 movie adaptation and press forward to look for more of the edgy anti-hero it contained. That issue didn’t turn me into a lifelong Spawn fan, my interactions with the franchise have been infrequent, even after becoming a professional comics critic. However, the early stories of Spawn have remained a part of my DNA as a reader. The aesthetic and style that were the definition of cool in the 1990s have continued to influence both my own habits and decades of comics to follow, leading to this week and the release of Spawn #300, a rare landmark for any series and especially for a creator-owned one. Given the history that followed and the immeasurable influence this one series has held, it’s worth reflecting on its origins that preceded comics Twitter, message boards, and most of the modern critical sphere. It’s worth reflecting and reviewing where this story began in the pages of Spawn #1.

Videos by ComicBook.com

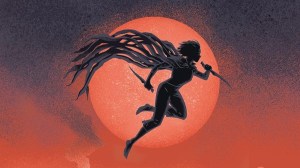

One of the familiar narratives to emerge in subsequent decades is that Spawn was designed so that Todd McFarlane could draw Spider-Man without splitting any profits with Marvel Comics. There’s a grain of truth to be found in the debut of Spawn as many McFarlane motifs transfer: slender forms wrapped in muscle, exaggerated violence, a cityscape steeped in shadows. There are a handful of pages that read as pure superhero comics. However, there’s an element of experimentation that is present throughout the issue, contrasting Spawn #1 against years of acclaimed work at Marvel Comics. In spite of the spiraling chains that bind both the titular hero and many panels in these pages, there is a feeling of freedom that forms the heart of this issue.

McFarlane is invested in trying new things, providing varying degrees of success. The countdown that measures Spawn’s limited access to power is an effective tool that is neatly bound into pages. Panels move further away from standard layouts than any individual issue of Amazing Spider-Man, and small alterations like panels spiraling in space maintain interest throughout this origin story. Almost no page is without some sort of gimmick or test that would inevitably inspire some of the many, many young readers who would go on to draw their own comics in the future. There are a handful of pages where a central figure is even eschewed altogether. McFarlane opts to focus on a feeling rather than a moment when Spawn’s iconic mask is set against the New York City skyline and fragmented images representing his own thoughts.

If freedom is the core strength of Spawn #1, then it’s the pages that resemble McFarlane’s prior work and the popular modes of the early 90s which hold up the least well. A big splash of Spawn posed with too many abdominal muscles and a cape swirling amidst wind seemingly blowing from every direction makes for excellent poster material, but appears dull when set side-by-side with far more complex pages. It is the red meat for the superhero base that briefly forgets about what opportunities the foundation of Image Comics presented its many talented founders. Pages like these have aged the least well, likely because they are the ones most regularly imitated by future generations.

Reading Spawn #1 in 2019 also serves as a simultaneous reminder of the most common critiques for early Image series, and how overblown these critiques have become over time. This debut delivers the essential origin of Spawn, but does so in a formulaic manner. Each sequence reveals one new element, none of which are particularly inspiring—the curse of power is really where this series’ greatest connection to Spider-Man rests. However, the plotting is rarely the point of the issue. While the earliest antagonists composed of generic street toughs and Malebolgia don’t stand out, the grotesque depiction of Malebolgia as a middle-aged heavy metal mascot complete with gut and bleach-blonde, long hair emphasizes an aesthetic approach. While the beats are familiar they are being played in a fashion that is delightfully indulgent. Mysteries and suspense are sprinkled in to provide a hook for future issues, but the real hook lies in seeing how these elements will be followed.

Al Simmons might be a sketch of a character, but he is an incredibly expressive sketch. One moment in particular stands out in returning to Spawn #1 almost 30 years after its initial publication and roughly 20 years after first encountering it. There is a panel in which Simmons screams in anguish upon remembering the wife he sacrificed his soul to see again. His mask is stretched taut across his face, emotion writ broad and projected loudly. It’s a startling moment and one that resonates throughout the rest of the issue, especially when Simmons discovers and mourns his deeply-scarred skin in a sequence relying on heavy shadows and contrast soon after. Moments like this create a strong reason to not simply read Spawn in its own day, but to revisit the earliest issues now. The power has not faded from these panels and it’s not difficult to see how they’ve continued to influence future generations of artists.

There are flaws, especially in McFarlane’s depiction of women and the clunky replication of Frank Miller’s TV talking head exposition, but these flaws have faded with age. Plenty of superhero artists repeat these stumbles each week in 2019. The highlights of Spawn #1 have only grown brighter with age, though. McFarlane’s readiness to try whatever most attracted his interest reveals the killer instinct that made him a star. Rereading Spawn #1 now reminds us that the series offered readers far more that was new, much of which is taken for granted now. It’s the foundation of a rare superhero series that could hold readers’ interest for 300 issues, and build an empire upon one man’s unique aesthetic. ‘Nuff said.

Published by Image Comics

On June 1, 1992

Written by Todd McFarlane

Art by Todd McFarlane

Colors by Steve Oliff, Ken Steacy, and Reuben Rude

Letters by Tom Orzechowski

Cover by Todd McFarlane and Ken Steacy