Image has published a lot of interplanetary science fiction titles over the last several years. Ranging from the exceedingly popular Saga to the critically beloved Prophet to the new favorite Copperhead, there has been a recent surge in comics focused on life beyond Earth. The science fiction genre itself is experiencing a revival at the publisher with a significant portion of their new series being steeped in biological and technological conceptions of the near and distant future. Drifter #1 certainly fits into this pattern of popularity.

Videos by ComicBook.com

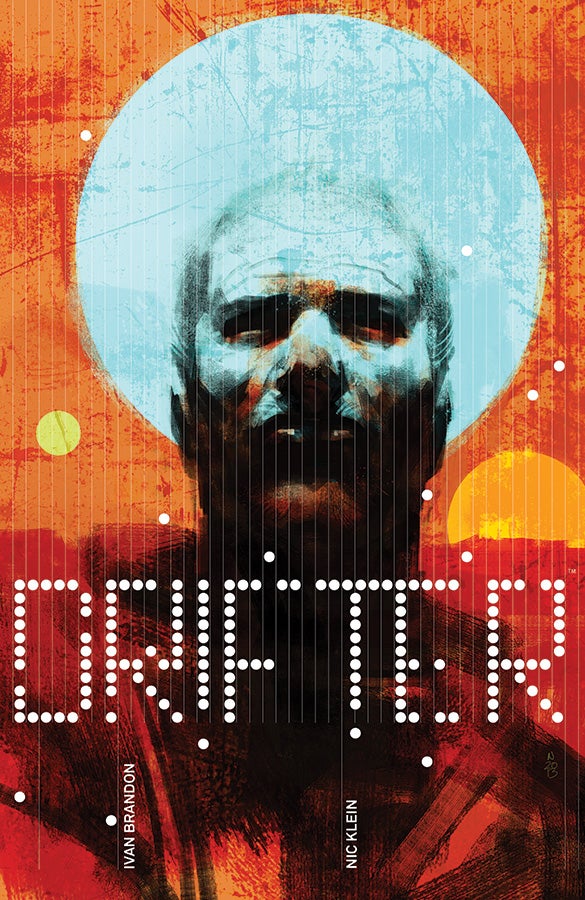

Ivan Brandon and Nic Klein’s Drifter is set on a distant world colonized by humanity. It features a starship pilot who has crash landed on the world not knowing what went wrong or where he is now. The setting he finds himself in is that of a space Western with a small town set in the desert, comparable to many scenes in Firefly or the setting of Copperhead. It is every bit as rugged as these comparable stories, but lacks their whimsical elements. Instead Drifter is almost overwhelmed by its nihilistic landscape.

What little there is to differentiate Drifter from the Western tradition is quickly subsumed into the bleak tone of the story. These elements are used to create a sense of place, but there is no joy in their discovery. The pilot responds to his discovery by an alien by promptly lashing out at it in violence. A gaseous drink is given to him, but its toxic nature is emphasized over its appearance. Even the appearance of a spaceship is used to make the world appear broken and devoid of wonder. The focus of this first issue is on the people who occupy this distant planet, the dregs of humanity.

Klein’s portrayal of characters is very rough. The lines in the pilot’s face are made out to be irremovable cracks in a mirror. Color work portrays him and most of the cast to be constantly in need of a splash of water, their faces and dress coated in a light haze of dust. Even the relatively good-looking Marshall is made to look worn down, her posture slumped and eyes tired. Klein’s figures create a consistent tone, but sometime appear to not be fully rendered. In a few odd instances, characters are flat against one another and the background.

The use and appearance of setting is much more consistent. Klein has composed an alien world that is every bit as harsh and uncaring as the people who occupy it. Although the world is alien, it reflects less beautiful areas of America’s Southwest. Mountains and desert are ruled over by a pair of twin suns. The light from these two stars that bounces off the dirt is colored to burn rather than warm.

The exterior landscape is gritty, baked in a perpetual planetary oven, but the interiors are no better. Inside of a bar, the colors turn from oranges and reds to a sallow green. The room is lit like a swamp and the clientele appear to be just as pleasant as the creatures one might find there. Although the bar is a retreat from the outdoors, it’s apparent that there is no escape from the ugliness of this place.

For as brutal as the mountains and desert are made out to be, there is still some beauty to Klein’s art. This is no place that one should desire to live, but there is a natural majesty to the landscapes of this planet. Klein does not portray ugliness by making his own work ugly, but by evoking specific thoughts and imagery through work that is capable of being quite beautiful.

That same level of definition is lacking from the characters who occupy the planet though. The pilot who crawls from the wreckage is never explored as an individual. Even when his thoughts are portrayed in text boxes, he only alludes to past events. His home, motivation, and everything else are all as mysterious to the reader as they are to the person who nurses him back to life. He is a cipher, resembling Western heroes in the tradition of Clint Eastwood, like the Man With No Name and Josey Wales. He is not given the space or opportunities to differentiate himself here though.

Two other characters are introduced in the first issue with considerable time to act: a priest and a marshall. They both appear more like caricatures from a Western than fully formed characters though. The marshall is well-intentioned, but world weary and cynical. The preacher is out of his depth, naïve and defenseless. These are character outlines that have appeared many times before, and they do nothing to differentiate themselves as being unique in the confines of this issue. There is also a mysterious stranger introduced early in the story. His actions and motivations are meant to be questioned. Yet the characters who act in the light of day are hardly more understandable than this man in black.

The state of this world and the universe at large are mysteries as well, but ones that function purposefully. Brandon always provides enough context for actions to make sense. The how and why of colonization are unimportant as long as readers understand the state of this world. There is a mystery about this world introduced by the end of the issue, but it is an effective driver of plot and character.

There is something missing from Brandon’s script: a connection with readers. Although the world functions within its own logic and the characters never fail to make sense, neither of these things resonate emotionally. There is no clear reason to invest in the pilot or the planet he has crashed upon yet. Mysteries alone are not enough motivation; something more is necessary to make people care about what is happening here.

Drifter #1 is another intriguing science fiction series from Image Comics. Brandon and Klein are constructing a world that may parallel other stories, but is truly its own. The tone of this tale is clear and while it reflect ugliness, Drifter is beautifully told. As the characters and ideas come into clearer definition alongside the art, it should make for an interesting ride.

Grade: B