I went to see the film Nebraska with three friends last fall. It’s a film that focuses on rural America and the experience of being part of a small community. We all enjoyed the movie to varying degrees, but I noticed an immediate disconnect when discussing it. The smallest city any of my three friends had lived in was Omaha, Nebraska with a population of about half of a million. I come from small town America though. That’s where my entire family lives. Although I live in Omaha now, I’m still constantly drawn back to small town America. Watching Nebraska, my friends saw a story about a culture they didn’t know was real, one they didn’t understand. It was still well crafted, but it didn’t necessarily ring true. When I saw the film, it floored me with its insight and emotional honesty. Alexander Payne, the director, is from Nebraska and captured what it meant to be part of a rural community. It’s the kind of experience you can’t explain unless you’ve really, truly been part of it.

Videos by ComicBook.com

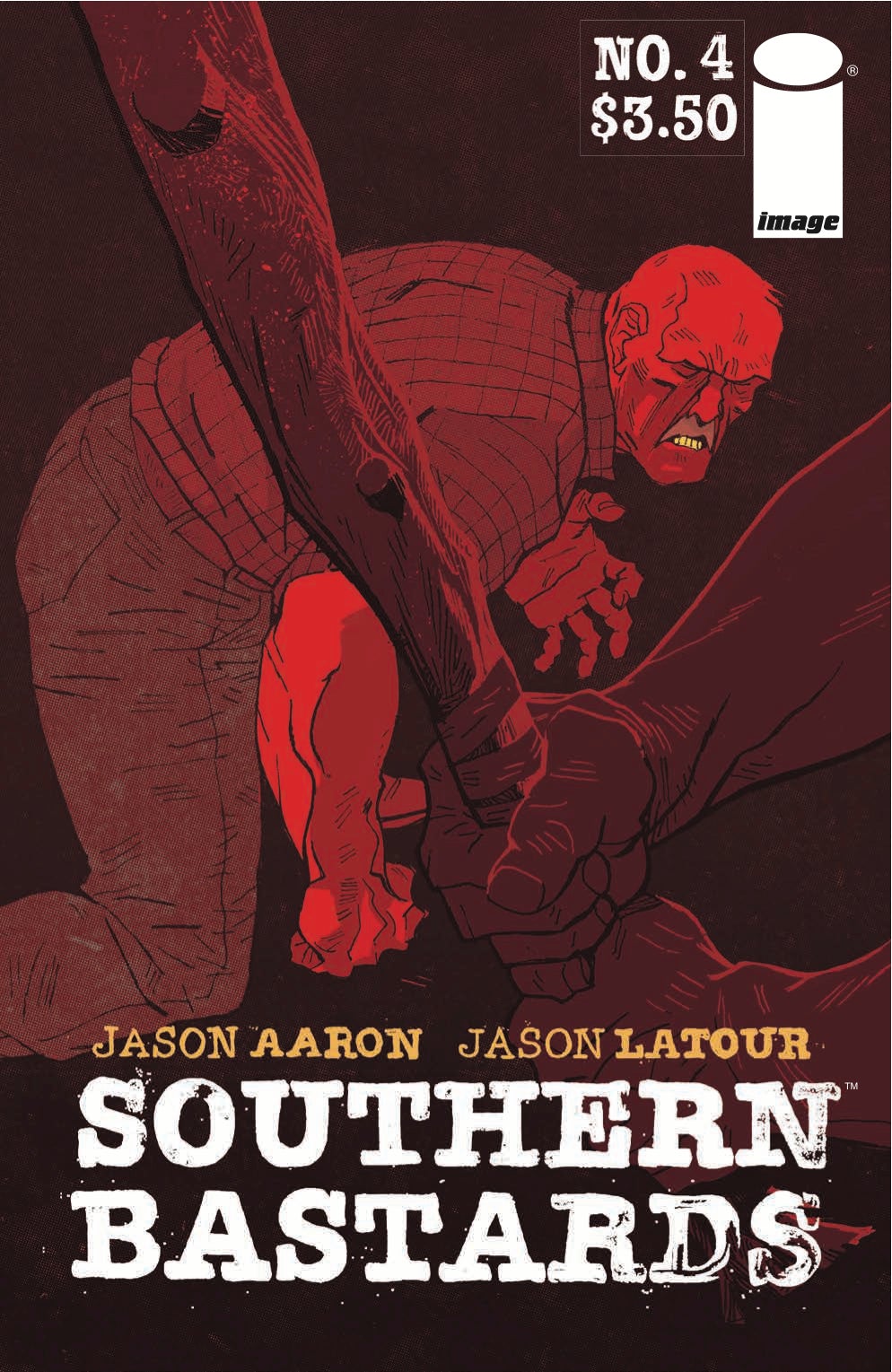

Every page of Southern Bastards makes it clear that Jason Aaron and Jason Latour have been part of it. They really know what it means to come from a place like Craw County.

Earl Tubb’s journey through the first four issues of Southern Bastards encompasses so much of what it means to be part of a small town. It’s often brutal and ignorant and uncaring. It’s tough and made so by the hard work and often harder conditions surrounding that life. It is an incredibly harsh atmosphere for anyone not willing to play by the rules determined without them. Yet it’s also home. It’s the place that gave birth to you and shaped you. It’s the place where your family is buried and that makes it impossible to not want it to be better. Despite all of the ugliness, you will never stop loving your home, even if you manage to leave it.

That’s a big idea, one I have a difficult time explaining in direct prose. That is what makes Aaron and Latour’s comic so impressive because it grapples with that concept directly and never missteps. They never attempt to romanticize or apologize for their subject, despite caring for it. Instead of searching for a way to explain the ugliness, they approach it head-on and let the blows of the story land hard and fast.

Southern Bastards #4 features plenty of both plot twists and fights, every one of which hurts. Latour’s art on the comic fits the needs of the story perfectly. It is every bit as rough and hard as the characters and actions present here. When a person is hurt, Latour makes the pain evident. It does not matter whether that pain is from the most obvious of wounds or a more subtle, internal aching. Every character’s face carries the full weight of what they are feeling. Most of these characters may be incapable of being open and honest with one another, but Latour’s depictions of their actions and emotions are completely honest.

Latour composes one fight scene in a two-page spread of twenty-four panels. It is magnificent. The sequence alternates between the present fight and the history of Earl Tubbs, moving between Latour’s typical color scheme and a monochromatic red respectively. Each panel of the fight provides just enough information to portray swings in momentum, but emphasizing the savagery of the conflict. The panels soaked in red put the fight in perspective though. It is not just a bare-fisted battle between men, but reflective of Tubbs and Craw County’s shared history. The fights in Southern Bastards #4 are not compelling only because they are well told. They are effective because they hold a greater meaning within the story as a whole.

The first storyline, “Here Was A Man,” culminates in the ending of a second fight. It’s every bit as brutal as every previous page, but the most painful moment doesn’t come from a punch. It arrives with a declaration. Southern Bastards has been asking why Craw County is like it is. What allows a place with good people to go so bad? The answer fits the tone of the story. Aaron and Latour don’t back away from the surprising, but ultimately inevitable, conclusion to their first story arc. They meet it head on and answer that question in an appropriately savage and terrifying manner.

You will cringe. It will hurt. This story is not for the faint of heart.

Southern Bastards isn’t a comic focused purely on the big ideas of what it means to come from rural America though. For readers who have lived that experience, the details will ring true. Latour’s depictions of Craw County and its inhabitants are rich with small nuances and features that bring it to life. The people of Craw County are covered in logos. In Nebraska you see John Deere and TSC (Tractor Supply Co.) everywhere. The same goes for less obvious brands like Tap Out and Kool-Aid. For some reason, logo adorned clothing flourishes in small towns.

The storefronts of Craw County with their idiosyncratic names and mascots ring true as well. Drive down Main Street and you’ll see the normal collection of businesses, restaurants, and shops, but none of them with a name like you’ve seen anywhere before. The mascot for Boss BBQ is an honest recreation of what you might find trawling through Alabama or Arkansas. For outsiders, these sorts of touches may feel like local flavor. For some of us, they just feel like home.

That is what makes Southern Bastards so powerful. Every bit of it is honest, from the characters to the brawls to Coach Boss’ BBQ. It’s all drawn and written to serve a story born from reality. There are no sequences that seem out of place or depictions that seem a little off. It is a comic that coheres perfectly together and bears out the needs of the story and its themes from beginning to end.

Southern Bastards works exceedingly well purely on dramatic terms. It’s a well-crafted story, expertly told by both Aaron and Latour. What sets this comic apart though is that even though it is fiction, it is entirely true. From the smallest details to the essence of its plot, every part of the comic functions to explore a truth about a certain sort of place and the people who occupy it. Southern Bastards transcends its medium and premise in order to seek what it means to come from a small town in America.

Grade: A