The Superhero Genre

Videos by ComicBook.com

A teenage boy with the proportionate strength of a spider lifts an enormous piece of machinery in order to save his aunt and stop a mad nuclear scientist. A man of steel sacrifices all that he is in order to care for those he loves most in his final story. An alien is convinced by a blind woman to rebel against his omnipotent master risking everything in order to preserve the planet Earth.

Amazing Spider-Man #33.

Action Comics #583.

Fantastic Four #49.

These are the sorts of high stakes and grandiose adventures that we associate with the superhero genre. Superhero: that combination of words perfectly describes these stories. They are epic tales of noble deeds that exceed believability and realism. That does not deprive these stories of power or merit though. There is a reason that the comics listed above and so many others by creators like Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko are considered to be classics of the comics medium. In these tales of fantastic families adventuring throughout the galaxy and men of tomorrow standing up for what is right, writers and artists have captured truths about the human condition. They are stories that connect with us on an honest, emotional level in spite of any unbelievable science fiction and fantasy trappings.

Power and impact in superhero stories don’t come from the scope of these comics though. Looking at Fantastic Four #49, “If This Be Doomsday!”, it’s easy to notice tangible details like the obvious threat of Galactus. Film Crit Hulk, the mysterious story diagnostician of Badass Digest, coined “The Tangible Details Theory” in this wonderful essay. What Hulk explains is that we naturally understand our reaction to a story, whether it is good or bad. We then explain our reaction based on the most obvious details, which are then based upon our level of understanding. Everyone understands how a story affects them, but not everyone has the same level of understanding of storytelling and language to understand why that is. In turn we address what stands out to us the most, the tangible details, in order to explain the why.

So when we look at a story like “If This Be Doomsday!”, the most obvious component is the arrival of Galactus. He is quite literally the biggest part of the entire story.He is a 30 foot tall alien prepared to consume the Earth and anyone living upon it. Not only does he intend to destroy this one planet, but he has already eaten countless planets like it already. It makes sense that if asked why this superhero story and so many like it are impactful and important, we might respond by addressing the enormity of the threat.

Is that really the case though? I don’t think so.

The State of The Avengers

Three Avengers comics were released last week (February 25th, 2015): New Avengers #30, Uncanny Avengers #2, and Secret Avengers #13. This collection of comics all released on the same week creates an interesting snapshot at the state of superhero comics. They each represent a distinctive ongoing story centered around the most successful franchise of the current most successful publisher of superhero comics.

Reading these three issues, the focus on tangible details from early successful comics like Kirby and Stan Lee’s Fantastic Four is obvious. All three of the issues contain big, universal stakes. They are focused on the enormity of threats that range from global destruction to the complete annihilation of multiple universes. All of these comics share the same massive stakes found in “If This Be Doomsday!”. However, they are not bland or unoriginal comics. There’s a clear authorial vision in each that makes them distinctive and worth examining individually.

What We Talk About When We Talk About Scope

Avengers #30 focuses on the return of Hank Pym to Earth and his explanation as to what has been causing the central threat of Hickman’s epic Avengers story. Pym details the various opposing groups they have encountered and his contact with entities like Builders and Celestials, revealing Beyonders to be the ultimate threat of the story. The scope is truly enormous. Hickman pulls from all of Marvel canon in order to establish a threat to all of reality.

This is far from the first time that such massive stakes have been summoned in the superhero genre though. The most obvious use of a multiversal threat is in Marv Wolfman and George Perez’s 12-part series Crisis on Infinite Earths in 1986. In that series the Anti-Monitor threatened to destroy all of the infinite universes that composed the DC Comics multiverse, but only succeeded in reducing them to a single cohesive earth and continuity. Wolfman and Perez established the grandest possible stakes, and their series is generally considered a success. That success isn’t based on the enormous stakes and threat present though.

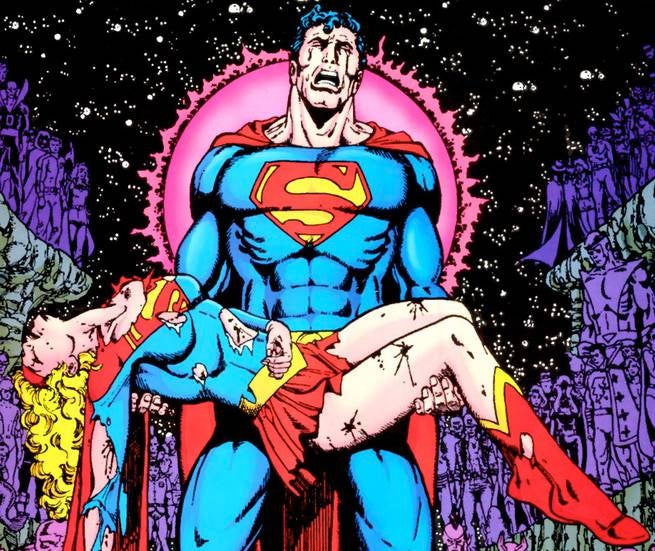

The most iconic moments of Crisis on Infinite Earths are all about characters. The deaths of The Flash and Supergirl, and Superman’s defeat of the Anti-Monitor all focus on the emotional stakes invested in those characters. These scenes are structured within the battle to save the DC multiverse, but they do not rely on the existence of the Anti-Monitor or his plot to end reality in order to function. The look on Superman’s face when he discovers Supergirl’s body, accompanied by decades of stories about both him and Supergirl, is what creates an emotional response in the reader. Crisis on Infinite Earths, Superman, Action Comics, and many other titles have detailed their relationship as friends, family, and partners. Her death is impactful because readers feel like they know Supergirl and can mourn her in the same way that Superman does.

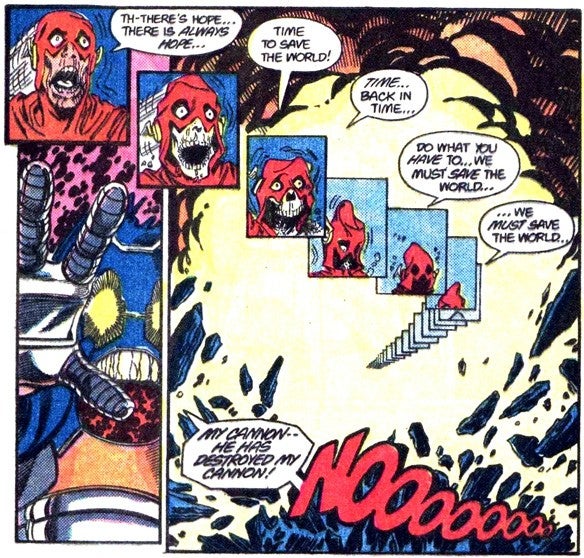

Whether it is the death of every person on Earth-6 or the singular death of Barry Allen, Crisis on Infinite Earths does not hold real consequences for the reader. Fictional characters are not entitled to an emotional response. Part of the magic of storytelling is creating an emotional connection between characters and readers, so that when a fictional construct suffers or dies it evokes a very real response. Perez’s depiction of multiple earths ceasing to exist is unable to create that response because there is no reason to care. Lady Quark watches her family and every other person on Earth-6 perish in a horrible fashion right before her eyes, but they are unknown quantities lacking in personality and substance. Barry Allen has been shaped by two decades of stories though. He is a man with a family whom he shares his hopes and dreams. Even in Crisis on Infinite Earths alone, Wolfman and Perez depict his internal struggle as he chooses to sacrifice himself in order to save the galaxy. The sadness that comes with the death of Barry Allen is derived from readers understanding him as a complete human being and emotionally investing themselves in his fate. It doesn’t matter whether he perished stopping the Anti-Monitor or dueling Captain Cold, his death would still be iconic because of his development and connection to readers.

The enormity of threats, both old and new, in New Avengers #30 doesn’t create the same impact as Crisis on Infinite Earths because Hickman’s focus is on the wrong details. In more than 80 combined issues of Avengers, New Avengers, and Infinity, Hickman has detailed the threat facing the entire Marvel Universe. As Earths continue to collide, either one must be eliminated or both universes will be destroyed. The focus of this issue lies on the universal mechanics behind this enormous threat. Those mechanics don’t matter without a reason to care though. The issue is consumed by exposition about the universal stakes, but fails to build an emotional connection between readers and the characters threatened.

Almost thirty years after the publication of Crisis on Infinite Earths, there’s no doubt that both Marvel and DC will continue to exist in some fashion. Marvel has already announced the ending of Hickman’s epic with the release of the Secret Wars mini-series. The scale of this threat is hardly reason enough to care. The problem confronting writers and artists of these series is to overcome reader’s awareness of this inevitable outcome. We are all logically aware that no character except Uncle Ben is dead forever, but great storytelling is capable of making us forget that by evoking an emotional response. The cold narration of New Avengers #30 serves primarily to remind us of the inevitable continuation of superhero sagas and events, instead of removing that sense of disbelief.

The Convenience of Genocide

The comparison between the death of Barry Allen and destruction Earth-6 makes for an apt point of comparison to Rick Remender and Daniel Acuña’s Uncanny Avengers #2 as well. The first eight pages of the issue detail a new civilization of animal-human hybrids living on the planet called Counter-Earth. They are shown holding hands, gathering as families, and caring for their children. Then they are all destroyed in a single detonation. It is genocide on an almost inconceivable scale, used to show how big the threat these heroes are facing is.

The use of genocide as shorthand for importance is not clever. Seeing families fleeing in terror moments after focusing upon their children creates an immediate reaction. Disgust and anger are a de facto response to such a horrendous display, but neither the set up nor the consequences are earned. All of the characters involved with the execution with the sole exception of the villain, The High Evolutionary, exist without context or complexity. They are generic families and beings being wiped out in order to establish the threat. It is genocide for the sake of convenience. There is no more depth to this sequence than to say that the High Evolutionary is bad because genocide is bad. It is an attempt to earn reader investment through scale rather than emotion, and it fails on a spectacular level. The feeling of disgust at seeing these people die is a direct reaction to one image. It is not something designed to resonate though. Instead, it is just as easily forgotten as the initial reaction was evoked.

This mirror scenes in early issues of Crisis on Infinite Earths in which entire planets were invented by Wolfman and Perez were destroyed in order to establish the threat of the Anti-Monitor. When Earth-6 is destroyed in Crisis on Infinite Earths #4, it is not a moment that sticks with readers and draws them into the story, but a plot device designed to show the threat to the multiverse. It is an attempt to raise the stakes and the action of the story, but it is not why Crisis on Infinite Earths has remained a touchstone within superhero comics. Individual deaths like Barry Allen are much better remembered because they existed with context and history.

Both Uncanny Avengers #2 and the series’ previous volume have featured planetary threats as the eventual goal. Each series follows a line of rising action that is consistent with the simplistic three-act model of drama. In comics like Uncanny Avengers and New Avengers, action is primarily presented in terms of the scale of threats. Following this model, the introduction of a genocidal madman in issue two seems like a dramatic plot point and rise in action. However, the actual experience of Uncanny Avengers #2 results in a cheap emotional response that fails to invest readers in the story. Investment in a story is something that must be earned. Fictional destruction does not create a reliable reason for readers to genuinely care about characters and events.

The New, The Uncanny, and The Dull

Both New Avengers and Uncanny Avengers are big stories. They are driven by the enormity of the threats faced by both teams whether it is the complete destruction of reality or genocide committed on a planetary scale. The stakes are unimaginably large, but the stories are dull by comparison.

Listening to Hank Pym explain who the Beyonders are and the threat they represent is not grounded in any sort of emotional response. The stakes feel fictional because they are plot-driven and addressed in an expository manner. New Avengers #30 is positively affected by reader’s external associations with characters like Captain America. Within the scope of Hickman’s story alone, Captain America and other characters are primarily driven by the needs of the plot and the threats they face. In the event Infinity, the story was about the Avengers battling the Builders and Thanos’ conquest of Earth. It and the stories that have followed it are plot-driven, not character-driven.

That sentiment is not as immediately applicable to Remender’s previous work on Uncanny Avengers, which centered around several key relationships. However, the first two issues of the new volume have only scraped the surface of characters providing summaries of their motives, but failing to tie them into the story. Instead the massive gut punch of destruction featured at the beginning of Uncanny Avengers#2 is used to substitute genuine investment in the story.

Both UncannyAvengers #2 and New Avengers #30 are primarily defined by the scale of the stakes in the stories. They lack the emotional resonance and response to a classic superhero comic like Fantastic Four#49. The most interesting aspects of either story comes from exploring the plot, rather than investing in and responding to the story itself.

The Secret of The Avengers

In comparison to comics like New Avengers, Uncanny Avengers, and many of the headline superhero titles being published by both Marvel and DC Comics, the scope of Ales Kot and Michael Walsh’s series Secret Avengers is typically miniscule. Many of the issues feature skirmishes with minor villains like Lady Bullseye or mad scientists with chessboards tattooed on their foreheads. As the series prepares to reach its climax in Secret Avengers #13, the scope has expanded to include the summoning of Tlön, an alternate reality that will unleash horrendous monsters onto Earth (and an allusion to a Jorge Luis Borges short story). At this point, Secret Avengers has matched the universal stakes of its sister titles.

The threat to Earth may appear to be large, but Tlön is an afterthought when compared to other conflicts within the issue. It receives about as much attention as the appearance of a deranged Deadpool breaking the fourth wall in Secret Avengers #13. The issue focuses primarily on the relationships between the characters instead, something that has been true of each previous issue as well

In the same way that New Avengers #30 focuses on Beyonders and Uncanny Avengers focuses on planetary genocide, Secret Avengers #13 focuses on the revenge of Snapper on his former boss M.O.D.O.K. The conflict may involve a planetary threat, but it is driven by relationships between characters. Snapper feels betrayed by both M.O.D.O.K. and society, playing a spurned loner archetype modeled after Gamergate figureheads. He is not destructive for the sake of destruction, but because of his feelings of loneliness and resentment. M.O.D.O.K. is not driven to save Earth by noble beliefs, but for his love of S.H.I.E.L.D. Director Maria Hill. These relationships contain farcical elements, as does the entire series, but they are grounded in relatable dynamics. Changing one’s goals for love or lashing out at friends who have left you behind are emotionally understandable narratives. No matter how much humor or intellectual tangents Kot heaps onto Secret Avengers, the core of the story is defined by its emotional core.

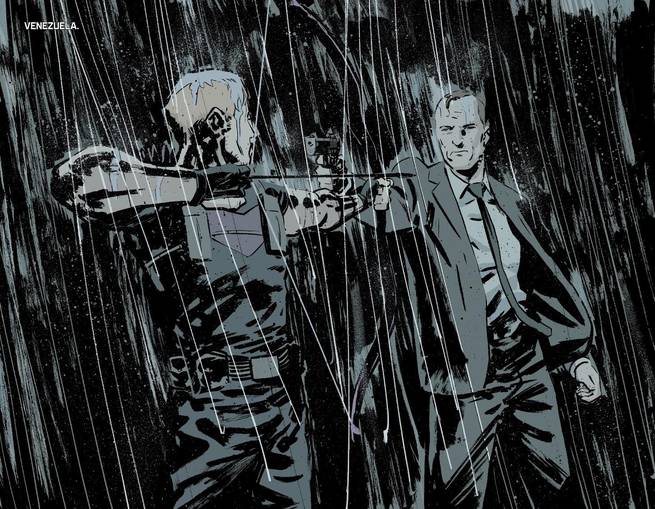

Nowhere is this more clear than in Secret Avengers #11, the beginning of the climactic arc. The issue centers around a confrontation between Hawkeye and Phil Coulson that has been building since Secret Avengers #5. Coulson, suffering from PTSD, went AWOL and has been tracked by Hawkeye after their mutual friend Nick Fury Jr. was put into a coma. They confront one another in the jungle with their weapons drawn. Their anger at one another and their own situations is driven by their roles as spies, fighters, and men. The climax of the sequence doesn’t result in a single arrow or bullet flying through the air though. It is resolved with an embrace. After Hawkeye informs Coulson of Fury’s situation he lowers his weapon and extends his arms, offering Coulson comfort in spite of their mutual animosity. The power of the moment is not driven by life-and-death decisions or the imminent end of the world, it is derived purely from the empathy and sadness expressed in this hug.

Yet this single moment is vastly more powerful than the revelation of multiversal monsters or the firebombing of a previously unrevealed planet. All of these sequences are fiction. No one is truly dying or threatened with non-existence. The moment between Hawkeye and Coulson feels real though, and that emotional response is something real.

Kot does not confuse size with importance in Secret Avengers. The romance between M.O.D.O.K. and Maria Hill is treated with just as much, if not more, gravity than the threat of Tlön. Tlön and other plot points defined by big stakes are no more important to an audience than a showdown between two friends in pain.

The end of the universe and destruction of an entire planet are unable to bring much beyond an initial shocked response without an emotional connection to define their significance. Yet a simple embrace offered to a friend in pain, between two characters who have been clearly defined by their actions, speech, and humor, is capable of eliciting honest tears and resonating with its audience after months.

Emotion Vs. Enormity

Consider comics outside of the superhero genre that are widely considered to be important or significant. Autobiographical comics like Craig Thompson’s Blankets or a sprawling space opera like Fiona Staples and Brian K. Vaughan’s Saga have elicited enormous reactions from readers. Yet they both hinge on stakes that are intensely personal. Stories in comics, or any medium, do not evoke reactions due to their universal stakes, but their emotional ones. The superhero genre is no exception, and the inclusion of global or universal threats are merely a genre trope, not a fundamental element.

In Fantastic Four #49, it’s easy to focus on the tangible details concerning Galactus, but this ignores the elements that elicited such an intense response in 1961, one that is still potent more than 40 years later. Over the course of 48 previous issues, Jack Kirby and Stan Lee constructed a cast of characters who readers cared about. Readers care about the Four not because of their fantastic abilities (plenty of other comics offer even wilder combinations of powers), but their relationships with one another and themselves. Whether it is the romance between Reed and Sue, the rivalry between Ben and Johnnie, Ben’s internal struggle with his condition, or any of the many other facets of these characters, they were drawn as complete human beings. We don’t care about the potential destruction of Earth, but the threat to these specific characters.

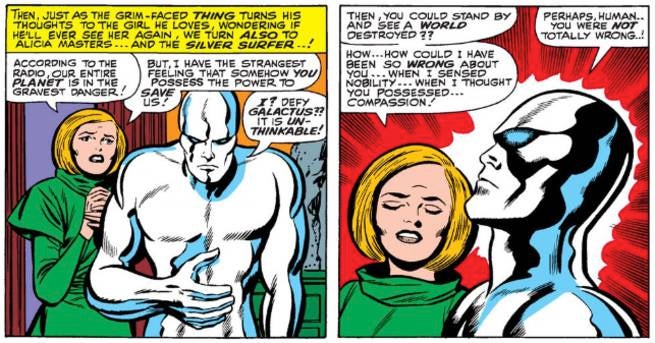

When the Silver Surfer chooses to betray Galactus in order to save Earth, no galactic imagery or depictions of Earth exploding used to define the moment. Instead, he is portrayed as a man who would risk the incredible gifts he has been given due to the words of a blind woman capable of depicting Earth’s beauty despite her disability. His conversation with Alicia Masters is the key to the issue, and it works because of how we relate to them and how they are shown relating to one another. There is an emotional core to these characters and their interaction that is far more honest and effective than any purple, thirty foot tall threat to Earth.

The spectacle of Galactus is an incredible element of the story, but it is not the heart of the story. Fantastic Four #49 is not a classic superhero comic because of the threat to Earth, but because of the manner in which a family handles this threat and the incredible sacrifice made by a new friend in order to aid them. Kirby’s big dynamic style does not exist solely to serve the universal stakes of the story, but to help depict the enormous emotional stakes. Many superhero stories have become so focused on the former that they have forgotten that only the latter is capable of affecting and resonating with readers.

That’s why a panel of Earth exploding isn’t half as powerful as two men hugging in the rain.