With only a cursory reading, The Multiversity: Mastermen #1 doesn’t appear to fit in with the rest of The Multiversity. The series has been defined by nuanced writing, tremendous artwork, and a complex, meta-textual narrative that functions both in individual sections and a whole. In comparison to previous entries, Mastermen #1 is a tritely plotted what-if story with the weakest compositions and designs of the entire series. The lack of surface appeal is purposeful, though. Every apparent weakness of Mastermen #1 works to obfuscate and outline its true meaning as an indictment of its publisher DC Comics, the superhero genre, and all of American comics.

Videos by ComicBook.com

Meaning of The Multiversity

When examining Mastermen #1 it’s important to consider the context in which it exists. Each issue of The Multiversity has been explored in immense detail by comics critics and reviewers, leading to advanced annotations and exhaustive explanations. This sort of layered complexity is not only a distinctive component of The Multiversity, but most of Morrison’s comics, including recent works like Final Crisis, Batman R.I.P., Annihilator, and Batman Inc. While the success of these comics may be debatable, their lofty intentions and exacting nature is indisputable. The disparity in quality and style between Mastermen #1 and other titles of The Multiversity as well as Morrison’s other recent work, is a call for further examination, not eager dismissal.

Each of the one-shot issues composing the body of The Multiversity has formed its own meta-textual narrative concerning the superhero genre and comics medium. Society of Super-Heroes#1 was an adventure comic that holds a great deal in common with the pulp novel predecessor to the modern comic book in narrative structure and genre trappings. It explores alternatives to the superhero genre that came to dominate the medium in the wake of World War II. The Just #1 is an awkward attempt to relate to modern trends and young people by exaggerating an adult look upon them. It details the disconnect between those creating comics and the generation at which they claim to be targeted. Pax Americana#1 is an examination of the exacting detail and aims of Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’s superhero masterpiece, Watchmen. It manages to criticize both the original work and its effects upon the industry. Thunderworld #1 takes a drastically different tactic, embracing the youth-oriented plotting of early DC Comics and applying some of the best modern talent of modern comics. It is an alternative to the other types of comics examined within The Multiversity, and the only comic unaffected by the corruptive antagonists known as The Gentry.

It’s even possible to look at these four in order as a historical sequencing of mainstream superhero comics. They move from an adventure story resembling the pulps of the 1930s and 40s to an adult attempt to relate to the modern adolescent experience like the early Marvel comics of the 1960s to the clockwork deconstruction and maturing themes of the 1970s and 80s to the diverse titles willing to embrace fun (like The Power of Shazam!) that sprung up at DC Comics in their wake. If that narrative is purposeful, it leaves Mastermen #1 in the massive boom-and-bust cycle of the 1990s and the modern comics trends that followed it.

This is nothing more than a brief survey of the commentary about comics and the superhero genre in display in each of these issues. They are brimming with ideas deserving of extended essays and thesis papers. Given the precedent set by previous issues of The Multiversity, it is difficult to believe that Morrison did not intend for Mastermen #1 to make a statement of similar scope.

Mastermen #1‘s Place in Time

Mastermen #1 is framed as a Superman story (ala the alternative name of Overman) beginning with an alternative origin and slowly building into a part of the larger narrative that connects all of The Multiversity. It also provides the first clues to Morrison’s intent by establishing a timeline. There are some discrepancies within the issue itself. Superman refers to himself as 98 years old at the end of the issue, but the captions clearly establish that he has only been on earth for 77 years. There are two jumps in time moving from his discovery to adulthood and again to the present. They are labeled “17 Years Later” and “60 Years Later”. Accepting these captions as basis of a timeline and setting the modern story in the year of publication (i.e. 2015), this suggests that Superman was born 77 years ago in 1938. This is the same year that the character was created by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster. It establishes that this is not only a Superman story, but a story about the character and his role within comics publishing.

Action Comics #1, published in June 1938, is widely considered to be the unofficial beginning of the superhero genre. Despite any technical challenges, Superman is viewed by the world as the first superhero. He is the progenitor of the genre, both its initial popularity and many of its tropes. A story about the character of Superman and the history of that character can also be seen as a story about the superhero genre.

The first jump of “17 Years Later” would suggest the year 1955 as the setting, although a later caption declares the exact date to be April 20, 1956. Both years signify a great deal of significance to American comics as historians mark them as the beginning of the Silver Age. While some contend it began with Detective Comics #215 (which featured the story “The Batmen of All Nations”, a prominent component of Morrison’s Batman stories) in 1955, others focus on Showcase #4 in 1956. 1955 was also a landmark year for Superman as a character with the publication of both Action Comics #200 and Superman #100. No matter the year, the cause and effects of this period are the same. The burgeoning of the superhero genre and success of DC Comics in these years was a direct result of the creation of the Comics Code Authority at the end of 1954 and the beginning of its enforcement in 1955.

The Comics Code Authority was a strict code of conduct created by comics publishers to self-police their content in order to appease public outrage brought about by Fredric Wertham’s Seduction of the Innocent and highly publicized Federal hearings. Without the CCA’s stamp of approval, most vendors would refuse to carry a comic book. It would effectively end the publication of most horror, crime, war, science fiction, and romance comics, leaving the superhero genre with little to no competition.

This time jump correlates with Overman’s conquest of America and, seemingly, the entire globe. He is a dominant force that has crushed American ideals of equality and justice. Imagery of an exploding Lincoln Memorial and defeated Uncle Sam are paired with announcements that proclaim a new reality, one that is “Beyond slave morality! Beyond the brute concerns of the herd!” It is a rejection of populism and socialism in favor of totalitarian rule.

The movement from the birth of Superman in 1938 to the conquering of America by Nazi Germany (and American comics by the superhero genre) are mirrored with the appearance of DC Comics in Mastermen #1. The issue begins with a splash of Hitler defecating in pain and holding an issue of Superman that features the titular character punching him in the jaw. Hitler’s pain stands in stark contrast to the triumphant moment displayed on the cover of the comic. 17 years later Hitler’s dream is achieved and comics are burned in massive piles. Instead of being juxtaposed to the suffering of the party, images of Superman are held by laughing soldiers.

This suggests a fundamental transformation, in which Superman has been transformed from a powerful concept to something laughable. Where the character began in stark opposition to fascism, he has now been co-opted by the ideology and used to destroy the power of comic books. The Superman conceived by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster in 1938 is one compared to the populist ideals of America in this era, whereas the one found in 1955 is a cog in fascist machine.

Lord Broken and The Gentry

It is after the story leaps forward again 60 years to the present day that the first element of connecting Mastermen #1 to The Multiversity appears in the form of Lord Broken. Lord Broken is a member of The Gentry, a collective of twisted beings destroying the many worlds of the Multiverse. Like everything in The Multiversity, there is more to these monsters than their surface. They are aware of comics as a fictional medium and make use of panels in order to attack Nix Uotan. The Gentry are suggested to be forces interested in corrupting the superhero genre and destroying comics.

Lord Broken is depicted as a tall, decaying house lurching to its side and filled with infinite eyeballs peering out of the windows. The frame has been haphazardly stacked forcing unsustainable growth on a constantly declining base. This appearance would suggest a connection to “The House of Ideas”, a famous nickname for Marvel Comics. On a deeper level, the combination of this name with the villainous intent suggests an ironic reversal where the vaunted house of ideas is completely lacking in originality. This twist would not be limited to one publisher, but any that rely primarily on intellectual property created decades prior. It is a criticism not just of Marvel Comics, but of its primary competitor and many of the smaller companies who apply similar strategies to marketing familiar concepts.

Overman is haunted by a nightmare in which Lord Broken looms over him each night. He describes the monster: “A broken house. Impossible to repair… A great, vacant building – its timbers cracking, the moulding rotten. The floorboards crumbling underfoot… yet still alive with some malevolent emptiness.” Taken as a criticism of the largest publishers of superhero comics, it is a potent image. The luster and beauty of a household are in decay having lost the ability to foster any life, but maintained in spite of its terrible existence. It is a brutal and absolute rebuke of the continued publication of characters like Superman by these publishers.

Lord Broken is shown looming over an homage to Crisis on Infinite Earths #7 in this dream sequence. That image drawn by George Perez in 1986 has become so iconic that it has permeated superhero comics for almost 30 years. It and the event that surrounds it have come to define much of what has been published in its wake. From the proliferation of crises and events at DC Comics to the repetition of nostalgia-filled frames from the 1980s, Crisis on Infinite Earths supports the threat represented by Lord Broken. It is an idea that has been repeated so often that the paint and moulding have worn down to reveal a broken shell of a house. The monster that looms over the character of Superman is DC Comics.

References and Meta-Text

Overman’s existence in the present is loaded with references suggesting connections to the publication history of Superman and criticisms of the publisher. These range from surface links to comics in the New 52 publishing line to allusions to classical opera.

Lena, a Lana Lang and Lois Lane analog, has been kept in a youthful state by Overman’s stem cells. However, they are running out after twenty-five years and Lena lashes out at Overman about her own mortality. He attempts to calm her by explaining “There was only ever a limited supply.” This suggests that even these fictional characters face a limited life span, that there are only so many Lois Lane or Jimmy Olsen stories to be told before they appear as transparent as ghosts. In Lena’s eyes only Overman can continue forever. The character of Superman is made to be something special in this alternate universe of iconic characters. He is the one with limitless potential who must discover new relationships when previous ones fade. Morrison has already suggested a relationship between Overman and the Nazi Wonder Woman analog earlier in Mastermen #1. Her chastisement of Overman and their relationship suggests a comparison to the new romance between the two in the pages of the New 52.

In Mastermen #1 Kara, the Supergirl analog, was cloned directly from Superman. She is literally of the same DNA as the first superhero of this world. This, the extended life of Lena, and the proliferation of superheroes only in the wake of Overman’s appearance all suggest that his DNA is both metaphorically and literally woven into everything around him. He is the constant that gives birth to these characters and the only element which will continue to exists indefinitely. Even classic standards like Batman and Aquaman are killed in a less than heroic manner in Mastermen #1. Overman is focal point from which everything else springs.

The immortal, classic quality of Superman is again raised in the form of Wagner’s Götterdämmerung, an opera commonly known in English as “The Ring of Nibelung”. It is an epic piece that typically spans four days and upwards of 15 hours. The connection between it and the superhero genre seems clear, especially given the ideas detailed in Morrison’s Supergods. They are both stories containing many characters with massive scope and power, and the core of both Wagner’s work and Siegel and Shuster’s creation has persisted through time. The final section of Götterdämmerung also shares a title with the famously untold Alan Moore story that would have shown an ending to the heroes of DC Comics: “The Twilight of the Gods”.

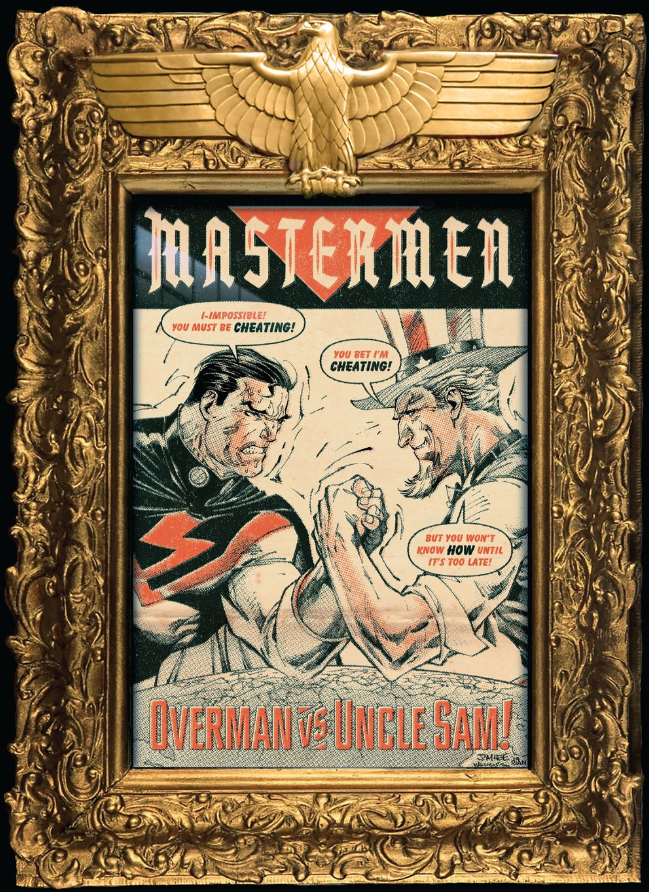

Jim Lee’s cover of Mastermen #1 itself serves as a piece of criticism. The original cover, also drawn by Jim Lee, depicted Overman and Uncle Sam arm wrestling over the earth. It is an unengaging piece of art with the rushed appearance of much of Jim Lee and his Image colleagues’ work from the early 90s. The final cover has taken that image and placed it in an elaborate, gilded frame with a swastika placed proudly on its top. This lackluster image with washed out colors has been treated with the same prestige as high art by the fascist regime. Lee’s art, no matter its merit or quality, is treated in a similar manner by both Overman’s government on Earth-10 and DC Comics in reality.

The biggest mystery of Mastermen #1 and, perhaps, the key to resolving what is actually occurring within the meta-text of the story is that of the narration. A narrator first emerges in 1955. It discusses the events of that day and the present in the past tense suggesting an omniscient perspective, aware of what was happening at each moment in time no matter how private or mysterious the circumstances. Although the narration is set alongside Jürgen, a Jimmy Olsen analog, in such a way as to make them appear connected, there is never a definite link established. Most of the captions appear in a way that recommends them to be an outside observer, someone who is aware of everything that happens in both Mastermen #1 and The Multiversity. The only man who fits this description is the writer himself: Grant Morrison.

Reading the narration of Mastermen #1 from Morrison’s perspective clarifies many of the lines that are left unresolved or ambiguous if the narrator were Jürgen or another character. In the same sequence where Jürgen appears to be the narrator, Morrison writes, “I got closer than any of the others – but when I found out what he’d done – I helped DESTROY him.” Jürgen is not suggested to be specifically close to Overman, he does not explain these crimes (and is shown to be a proud member of the Nazi party), and is not implicated in any part of Overman’s downfall. Morrison can be connected to each of these elements.

Morrison has written three of the most iconic Superman stories of all time and has been widely lauded for his understanding of the character in works like All-Star Superman, JLA, and the second volume of Action Comics. The undefined crimes are defined by the first two acts of Mastermen #1 in which Superman is converted from a populist hero to a fascist symbol. Overman’s downfall in the final pages of Mastermen #1 can be connected to The Gentry or Uncle Sam or the Freedom Fighters, but the man ultimately responsible is Grant Morrison. He has indicated a belief that he and his work are directly connected in past comics like Animal Man and The Invisibles, and has taken responsibility for both what he writes and the supposed effects of that writing on reality. Morrison is the only cypher through which the narration makes sense.

Superman and DC Comics

Morrison’s previous work with the character of Superman suggests a deep affection for the character, its cultural relevance, and ideals. The sudden reversal is not against the character Morrison wrote about in All-Star Superman, but what the character has become. The ultimate antagonist of The Multiversity is The Gentry, not Overman. The greatest threat in Mastermen #1 is the Nazi party, not Overman. He is horrified by the mass genocide committed by Hitler’s regime, but is incapable of opposing it and reaps all of the rewards. Rather than working for an active good, Overman has been reduced to a passive observer of atrocities.

The greatest flaw of this version of Superman is not that he is evil, but that he is impotent. At his conception in the opening pages of Mastermen #1, he is turned over to Hitler to be shaped for his own needs. The dream of a socialist hero, the type of hero Morrison has always written about and who he has claimed to be inspired by the original ideas of Siegel and Shuster, was present in those moments but was not made into a reality. Rather than being a man of the people, he is handed over to Hitler by a farmer in the conquered Sudetenland. The connection between Siegel and Shuster, sons of European immigrants, and Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson, the comic publisher who would purchase the character for only $130 are clear enough. It is a transfer of an iconic hero created by the working class to a corporation seeking to capitalize and control that creation.

As hyperbolic as it may seem, it appears that Morrison is comparing the comics industry to the Nazi empire of Earth-10. They both rose to almost complete power in 1955 crushing alternatives and controlling all of the most popular ideas. The result is a “virtual paradise”. It is a world that is beautiful and without change on its surface, but also one that lacks a diversity of ideas or options. There is a beautiful surface that has been built on mountains of dead bodies.

Overman is shown overlooking those bodies in horror saying, “I was only gone for three years. What have you done?” Those bodies can be perceived as the ideas, publishers, and careers crushed by the CCA. The rise of DC Comics, and later Marvel, was structured upon the artificially constructed monopoly of the superhero genre. Those bodies can also be seen as Siegel, Shuster, and many of their peers. The creators who invented most of the ideas that these comics empires are built upon have seen little to no profit for their ideas. While the legality of their treatment may be indisputable, the morality of the system in which they created multi-million dollar properties for only a few hundred dollars is another matter altogether.

So when Overman is shown in a world on fire at the end of Mastermen #1, he is shown to be repentant. The narrator proclaims, “He only wanted to end his guilt. He wanted an end to his loveless relationship. He wanted an end to the bloated, self-satisfied Thousand-Year Empire.” Again this works on multiple levels. While it can reflect the character of Superman unable to rectify his noble beliefs with what he helped accomplish, it reflects that same mentality within Morrison. He is unwilling to accept the current state of the American comics industry, rejecting the publishers who profit from controlling the work of dead men who made only a pittance for their greatest ideas.

Morrison’s collaborator in this endeavor could not be a more perfect illustration of this message. No artist is more representative of modern superhero comics than Jim Lee. He is one of the definitive artists of the 1990s, both redefining the X-Men at Marvel and helping to found Image Comics in 1992. Lee then went on to join DC Comics as co-publisher in 2010, and was the man who re-designed their most iconic heroes for the launch of the New 52. The presentation and new costume designs of the Freedom Fighters in Mastermen #1 serve as a callback to the unveiling of Lee’s Justice League less than four years ago. No other artist has had a greater impact on the continuation of superhero properties in the past twenty years.

Grant Morrison and DC Comics

That Mastermen #1 was not only published by DC Comics, but drawn by its most prominent artist and co-publisher makes Morrison’s criticisms of their business seem all the more extraordinary, bordering upon ludicrous. That is the trick of the story though. Everything interesting and engaging about Mastermen #1 occurs in sub-text and metaphor. On its surface it is a mediocre story in which Superman was raised by Nazis. Outside of some poorly explored moral lessons, it raises nothing of value on its surface. Yet it is set within one of the most complex meta-textual explorations of the comics medium and superhero genre to be published in years. It demands a deep reading and interpretation to be understood.

Morrison is aware that nothing on the surface of Mastermen #1 could be perceived as an assault upon his publisher or collaborators. That cognizance is what has allowed him to write a comic that contains ample evidence of this criticism without any of it being immediately obvious. Morrison has described himself as a wizard before, capable of manipulating reality through fiction. In Mastermen #1 he has pulled off his greatest trick to date. He has transformed himself into a trickster. Morrison is the Bugs Bunny to DC Comics’ Daffy Duck and he has just convinced his benefactor to declare duck season.

That relationship makes Morrison’s message in Mastermen #1 a potentially untenable one, though. He may be pointing to the emperor’s lack of clothes, but is not working to affect any change. Any criticisms he lobs at DC Comics and Marvel Comics are coming from a writer who has profited from their immense backlog of intellectual property and continues to do so. In addition to his many comics featuring Superman, almost seven years of Morrison’s career were defined by his ongoing work with the character of Batman. This is work based on the creation of Bill Finger and Bob Kane, the former of whom continues to not receive any credit and whose family has not received any compensation for the continued use of the character.

Morrison is not unaware of the hypocrisy of this stance. He is a man benefiting from the past misdeeds of a corporation that supports and adores his every whim. What Superman is to the Nazi empire of Earth-10, Grant Morrison is to DC Comics. They are both wracked by guilt at the circumstances that have allowed them to succeed, but unwilling to openly speak out against their benefactors. In the final panel of Mastermen #1 Superman is shown on his knees bent over with sorrow and guilt with his eyes pointed at the ground. Beneath him lies the title of the issue “Splendour Falls” along with the credits. At the very bottom of the page in the smallest font of all lie the names of the men who created Superman and sold him for only $130: Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster.

Instead of being an open challenge and scathing indictment of the industry that provided Morrison with so much success and freedom, Mastermen #1 is a comic written in code. Morrison’s guilt and anger are seething just below the surface of the issue, but like this incarnation of his beloved Superman, he is unwilling to tear down the utopian facade in order to expose the problems that lie beneath it. Instead, he chooses to play the role of the trickster. The joke is there for anyone willing to read into it, but it is too obscure to risk any actual harm to Morrison or those he is challenging. While Mastermen #1 is a complex read filled with meaning and craft, it is no more capable of driving change than a shotgun blast in Loony Tunes.

– – –

Want a chance to win a Batman Arkham Knight Playstation 4 Bundle? Click here or the image below to enter!

Good luck!