What are our criteria? Well, there’s a few things. Patriotism is certainly a tricky thing to define, particularly in a culture born in revolution and that still encourages the underdog mentality. I’ve always argued that, no matter which party is in power, questioning the government’s actions and policies is not inherently unpatriotic, although questioning its validity or authority without good cause tends to tread the line.

Videos by ComicBook.com

There are, of course, plenty more patriotic heroes who don’t make the list. The Shield predates Captain America, for instance, and characters like The Fighting American, U.S. Agent, Wonder Woman and bunches more could lay claim to a spot on this list. Space isn’t unlimited, though, and these felt like both a representative sample and in a coupel of cases characters readers might not be familiar with or have heard of (you should — go buy some books with those characters).

So rather than build a strict set of criteria, we’re going to select some characters who feel like they belong on the list, and then compare and contrast how they fit with the other candidates as we go.

There may be more comic book covers featuring Superman with an American flag, U.S. servicemen or a bald eagle than any other comic book character in existence. Part of that is likely just his longevity, but obviously there’s somewhat more to it than that.

Superman battles for “truth, justice and the American way,” as everyone learned from watching The Adventures of Superman on TV at one point or another in their lives and, even with a one-off story about him renouncing his U.S. citizenship (we’ll get back to that in a minute), he remains a uniquely American icon.

Superman is frequently cited as the ideal immigrant story; born somewhere else, he came to the U.S. out of desperation and ultimately made the country a better place to be with his presence. That he’s a “citizen of the world,” someone who serves the interests of humanity at large, has sometimes led to conflicts when his actions are perceived as those exclusively of the United States, which is what led to a that David Goyer-written story where he renounced his citizenship. In spite of being a short story in an anniversary issue that was likely never intended to have far-reaching consequences, the outrage over Superman (not Clark Kent, mind you) renouncing his citizenship was so furious that simply not addressing it wasn’t enough and it ended up being “fixed” in-story.

Of course, as overblown and absurd as that story got, it speaks to a larger part of Superman’s character: that his premise is that he’s a Messianic figure and someone who is ostensibly the human ideal, not just the American one.

This one is interesting, of course; invented specifically to answer the call for patriotic superheroes in comics’ Golden Age, Uncle Sam hasn’t been particularly relevant for modern audiences, and frequently there’s difficulty finding just what to do with he and his group of Freedom Fighters.

As the living embodiment of the American spirit, he certainly seems like an ideal candidate for this list; whatever the soul of America, he’s ostensibly in tune with it. That he’s fairly rarely used and poorly-developed in modern times means that he also hasn’t had to grapple with issues like Superman’s citizenship or Captain America’s run-ins with corrupt power. That can count for or against him in this argument, becuase while it’s the pure, unquestioning love of a child or a dog, that kind of love can be simplistic and easily challenged.

That’s something we saw in Steve Darnall and Alex Ross’s U.S., when the “classic” Uncle Sam found himself homeless and penniless, living on the streets while a “modern” Uncle Sam that was less about altruism, responsibility and virtue and more about capitalism stepped into his role.

That story worked fairly well, but it was one told outside of the DC Universe. In-universe stories with Uncle Sam tend to be hamfisted and feel out of character when he’s forced to confront such issues (see above), likely in no small part becuase you also have to deal with whatever superheroic issues are going on at the time. As someone who hasn’t had a solo title in years, it’s difficult to challenge his worldview without that subplot taking over and feeling like it’s distracting from the larger narrative.

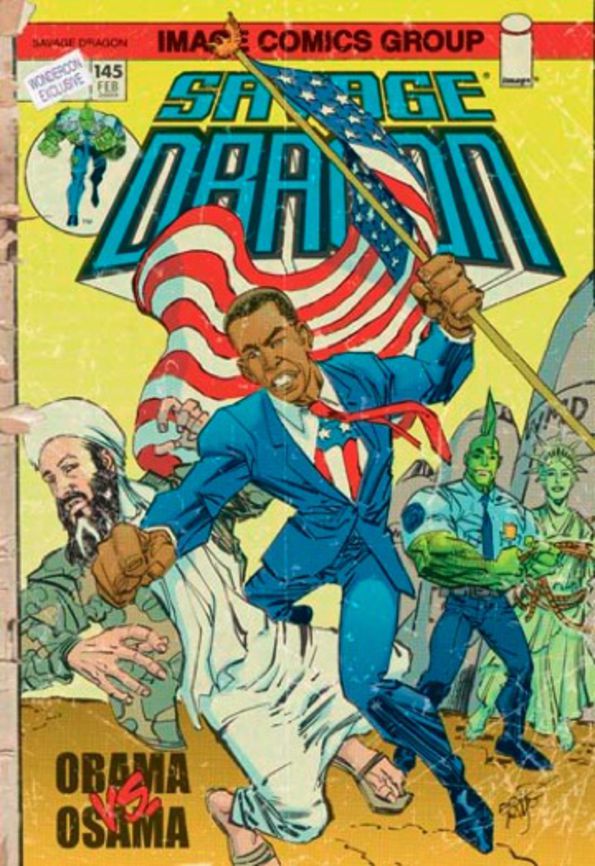

Erik Larsen gave comic book readers a version of Captain America in Savage Dragon who, before we ever got to know him, had experienced a horrible loss and drifted more into Iron Man territory.

John Quincy Armstrong was a promising student and athlete who left all that behind to join the military on the day the U.S. and Nazi Germany officially went to war. Instead of being treated with a super soldier serum willingly and by his own government, a la Cap, Armstrong was injected by Nazis who felt their attempts to build a super-soldier had lost them too many of their own best and brightest during human testing. When he was successfully imbued with powers, though, he leveled the place and made his escape (along with other prisoners of war he’d been held captive with).

Later in life, after being horribly mutilated during a fight with freaks in the early ’90s, he was experimented on again — this time by the mob, and this time to grant him even more extraordinary powers via nanotechnology. After being briefly controlled by the criminals who restored him to live and vitality, he reclaimed his humanity and resumed his role as a government superhero-for-hire.

That’s a big theme here; while many patriotic heroes step away from the life at one point or another, SuperPatriot actually has worked for the government more or less continuously in various ways since the ’40s. While it’s easy to say, “Oh, he’s Larsen’s version of Captain America,” he’s actually arguably closer to Nick Fury.

Oh, yeah. And he had a relationship in the ’70s that yielded two children: a son and a daughter. They’re twins. Their names are Liberty and Justice Armstrong, and they were born on July 4, 1976.

Created by J.M. DeMatteis and Mike Cavallaro, Savior 28 began its life as a Captain America story, but didn’t see print for 25 years after its initial conception and by then there was never any consideration of DeMatteis going back to Cap for it.

He told us:

Back in those ancient days of the early 1980’s—I think it was ’83—I was finishing up a year-long storyline that culminated in the death of the Red Skull. I began to question where Captain America would go from there. What would this man, who’d been waging war, punching faces, dropping buildings on the bad guys’ heads, for (at that time) forty years, do once his primary opponent, a guy he’d been battling since l940, was gone. Knowing Cap—well, my interpretation of Cap—it seemed logical to me that he would have reached a point where he said, “Enough! I’ve been doing this for four decades and it hasn’t made the world a better place or me a better man. Violence is a dead end and I have to chart a new course.” This would also allow me, as a writer, to deal with my ambivalence about the role of violence in super-hero comics, something I’ve always been extremely uncomfortable with. Don’t get me wrong, I love these characters—they resonate on so many wonderful, mythic levels—but most super-hero stories come down to two guys in costumes beating the crap out of each other. Not exactly the most enlightened point-of-view there is. In fact, it’s a fairly stupid and destructive one.

I worked up a proposal for a pretty massive arc that would find Cap becoming a global peace activist. (Which would freak out both the government and his fellow super-heroes.) It all culminated in Cap’s assassination at the hands of Jack Monroe, the Bucky of the 1950’s. Now this was a fairly radical idea for its day—but my editor, the late, great Mark Gruenwald, liked it and was willing to go out on a limb with me. Jim Shooter, on the other hand, was totally against it. (As editor-in-chief of the Marvel Universe, and custodian of those characters, he had every right to feel that way. And, looking back, I can understand why a story that questions every super-hero’s reason for being wouldn’t work within the context of that shared universe.) So the idea went down in flames…and I’ve been playing with it—peeling it apart, putting it back together—ever since. Trying to find just the right vehicle for the idea.

Any of that sound familiar? By the time The Life and Times of Savior 28 came out from IDW in 2009, Captain America had already indeed been assassinated.

His origin story is more or less Captain America’s; his power set is more in line with Superman. In any event, he ultimately became a political activist, hoping to uphold his principles of peace by doing something with his powers other than dropping building on bad guys. That went about as well as you’d expect, though, and Savior 28 was killed. It was his longtime sidekick who did it, and then narrated the miniseries (distraught, he took his own life and his suicide note as used as a framin device).

He only appears in one story — which you can buy on ComiXology for less than $10. Do I think you should? Well, I’m quoted on the cover as saying it’s one of the finest superhero stories of the decade. So yeah.

Okay, it’s Captain America.

Patriotism is so engrained into Cap’s persona that many of his most traumatic experiences are actually viewed through that prism. It’s also no accident that when people make their own “patriotic superhero” character, it’s often suspiciously close to the story of Steve Rogers (we’ve included some above).

When Cap is betrayed by President Clinton, who declares him a persona non grata after falling for the Red Skull’s trickery, he forgives, forgets and shakes the President’s hand when he comes back, his faith in America not wavering, his desire to punch the commander-in-chief choked back.

Captain America’s writers don’t generally shy from the hard questions about the character and the country, either; he’s dealt with Nixon as a villain in the book; he’s dealt with prisoners of war and PTSD, losing his friends in conflicts for decades. He’s clashed with his own government and gone against orders when he believed he was upholding the Constitution and American ideals more than the government was. Cap, just an unexecptional kid who wanted to do something for the country he loved, is the perfect political superhero and the perfect American patriot.