When it comes to genres, there are few more complex, varied, and satisfying than sci-fi. It’s a genre of adventure, wildly imaginative stories, and frequently tales of revolution that prompt the audience to simultaneously enter a world of “what if” and examine elements of their own lives and existence as well. It’s something that comics as a format does very well and there is one comic in particular that is not only an example of what good sci-fi can do but is redefining what to expect from stories of revolution.

Videos by ComicBook.com

That comic is Free Planet from writer Aubrey Sitterson and artist Jed Dougherty. Published by Image Comics, Free Planet kicked off earlier this year and quickly took the genre by storm with its “well, now what” tale of a post-revolution world where total freedom has been achieved but now, the victors have to maintain the new total freedom state while also figuring out what total liberation actually looks like not only for their world of Lutheria, but the world beyond.

With the pivotal sixth issue headed to stores October 8th and the first trade coming to comic shops November 26th, ComicBook sat down with Sitterson and Dougherty to talk about Free Planet, the inspirations, influences, and detailed research that went into building the world of Lutheria, as well as what’s on the horizon for one of the most original and fascinating comics in years.

Note: this interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The (Well-Researched) Origins of Free Planet

ComicBook: Where did the genesis of this world come from? Reading this, I feel Star Wars. I feel Dune, but it’s also entirely different and original in a lot of ways. It also reminds me of some of those weird ‘70s sci-fi movies that would play on local access channels when I was a kid, especially as we get later in the story and the alien that looks like he might be a squid merged with a harp. Where does that come from?

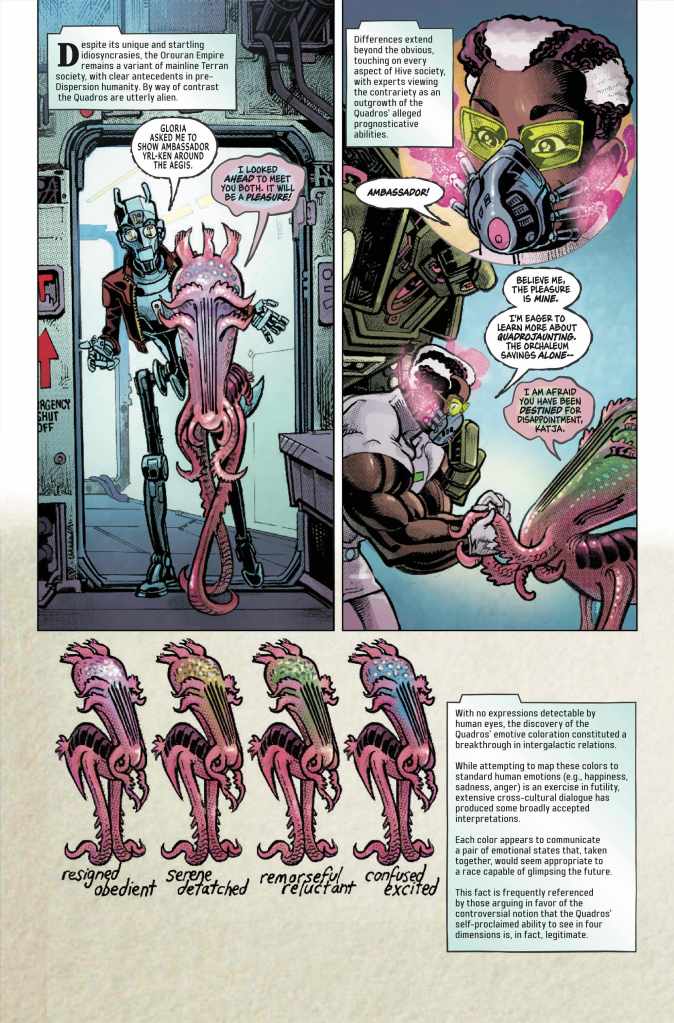

Aubrey Sitterson: So, there’s not really a simple answer to where all this stuff comes from because, I don’t know if I’m wrong, Jed, but Ambassador Yrl-Ken just came out of your brain, right?

Jed Dougherty: Yeah, I think Aubrey just said we needed an alien.

Sitterson: Yeah, we wanted an alien that felt truly alien. We didn’t want to have just like another humanoid with the Star Trek approach, right? Like, we have some of that too, with the Surroko people, for instance. So, the influences are really diverse and myriad. I’ve talked a lot about the research that went into it but I get the feeling that part of, at least part of what you’re leading to, was kind of the conceit, like the larger world of just kind of like the universe setup. And, you know, it’s a trope. It’s for sure a sci-fi trope, this idea of humanity has spread out amongst the stars, fallen out of touch with one another, and then got reintegrated through some kind of larger governmental structure.

I used to think this was a Dune thing or an Ursula Le Guin, Hainish Cycle thing and Jed and Howard Chaykin disabused me of those notions and said, “you need to read Cordwainer Smith.” He’s a foundational sci-fi writer. And he came up with that setup. He was the first one to do it. It’s a series of stories called The Instrumentality of Mankind. So, I went back and read all that stuff, that conceit and in terms of the sci-fi setup of Free Planet, it owes a lot to Cordwainer Smith. I think that’s why people get this kind of hit off of it like, “oh yeah, it’s kind of like Dune. It’s kind of like The Dispossessed. It’s kind of like Star Wars. It’s kind of Like Warhammer.” And the reason why people feel that way is because it’s pulling from something that predates all of that. And it’s more a foundation. It’s an ur-text for sci-fi.

The Psychology of Free Planet And Why Structure Matters

One of the things that kind of jumped out at me the deeper I got into the series is that there feels like some psychology in this as well. Just in the look on a specific character’s face at the end of issue six as they realize what’s going on made me think that there is a lot of human psychology in this. It made me wonder how much psychology research did you guys have to do for this, both in terms of crafting characters and in how they look and feel?

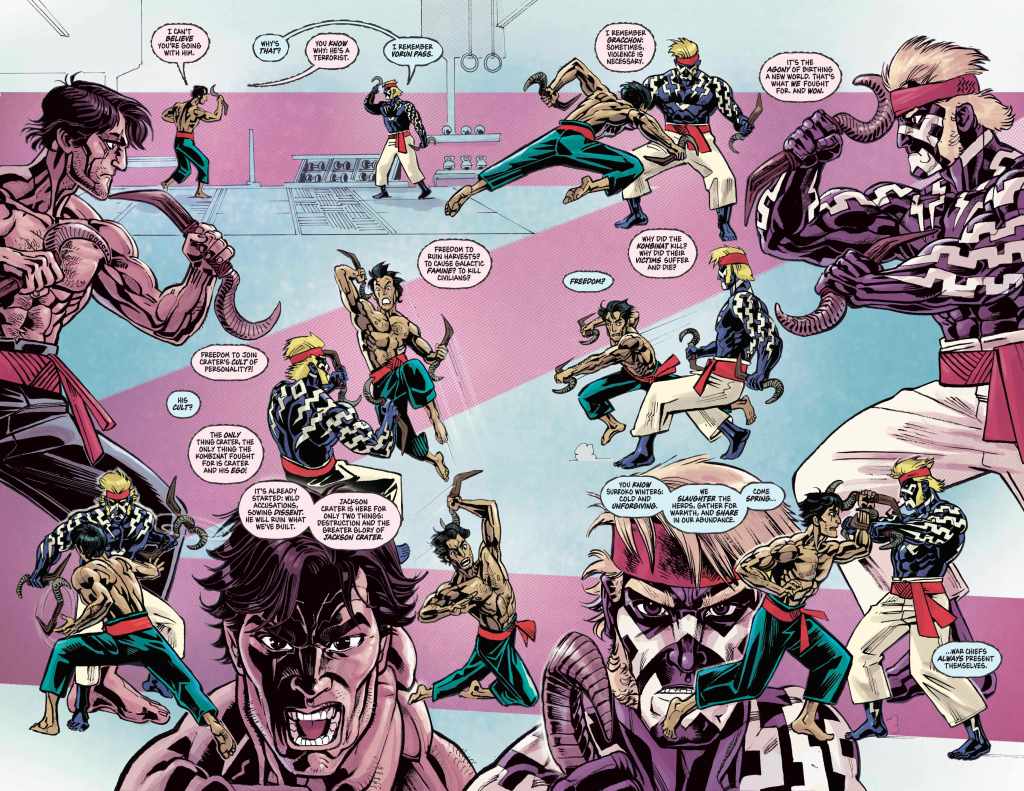

Sitterson: I think what you’re reacting to is Jed works traditionally. Jed inks and he inks on the page. He inks on the boards and does really lush, detailed, traditional ink work. It’s cliche to say it’s a lost art, but it’s definitely not as en vogue or as common as it was even 10, 15 years ago. And I think that’s certainly part of it. Also, I think credit for kind of like the lived in yackiness of this world, what makes it not slick sci-fi, is Vittorio [Astone, colorist] and what he’s bringing to the pages and the color. It’s one of the things that we requested from him, actually because we wanted this thing to feel a little big grungier and lived in and dirty.

The question of whether it’s utopian or dystopian is a really complex one, I think. Because they’re trying to build, it’s trying to be utopian and they’re trying to build a better world but it’s just not working all that well. So, we didn’t want it to look Star Trek slick because that wasn’t the world that they were saddled with. On the psychology, that’s a really fascinating question.

Dougherty: Maybe what you’re reacting to is that there’s not like any internality to the characters on the page. There’s no thought balloons, there’s no personal narratives or anything. So, all you’re going to get out of them is either outright declarations or their faces as they’re thinking about whether or not that’s actually true. So, it’s acting mainly. And Aubrey calls that out and I do my best to try and build that in. There’s a lot of people kind of getting themselves into some real muddled situations.

Sitterson: If you’re writing comics, you need to consider the head spaces of the characters that you’re writing. And if you’re drawing comics, you need to be able to, as Jed so eloquently put it, demonstrate and exhibit those interior spaces visually. Like that is the entirety of comics and I think what makes Free Planet stand out is it’s actually a formal thing that we do. This is something that I learned from Howard Chaykin. Every page, close up, direct eye contact with the reader, every single page, and at least one. And we do a ton of them. And this is only effective because of how good Jed is with these close ups and character reaction shots, close up, direct eye contact shots. A device we use is just a row of them and maybe some people have dialogue, maybe they don’t, maybe they’re talking over each other, but it’s a row. This is a row of these people looking at you. Using the close ups brings the reader in and forces them to confront the emotional states of these characters that otherwise they would not. So, I think it’s, at least partially, a formal thing.

Religion As A Cornerstone of Revolution

I also wanted to ask… you created your own religion — multiple ones — but Teomekhy in particular. Not to give anything away, but that becomes significant in issue six. How do you create your own religion and get the complexities but also reflect the humanity of it?

Sitterson: You know the religions are really important to Free Planet. All the research that I did, religion always has a role to play and it’s not always on the same side and sometimes it’s on both sides and sometimes there is conflict. I talk about the Spanish Civil War a lot in the context of Free Planet because I read a big influential book about it. And it was complex. You know, there was the church’s official stance, the Catholic church’s official stance and then there were individual actors within Spain who had their own opinions and were involved with all of the various factions. And that was a really influential thing for me to start thinking about.

I read another big history of Cuba and religion, both imported and homegrown religion has played massive roles in these places and it was important to me that we have a religious aspect to the narrative and Free Planet. And this is broadly true of the sci-fi setting as well, by making things different, by making up a new religion we get to kind of divorce ourselves. There are people who would read Free Planet and maybe have really specific ideas about Christianity or the Catholic church specifically and if we included those, or if I wanted to touch the third rail like Islam or Judaism. if I used any of these things people would come to the work with their own baggage and interpretations and feelings and views which runs counter to what we’re trying to do. We don’t want to make a statement about Christianity or Judaism or Islam. We want to explore these kind of even more foundational issues of freedom and how we kind of structure these worlds that we choose to live within and at the same time we don’t want to be beholden to kind of pre-existing baggage regarding these real-world elements.

It would be disingenuous for me to say that Teomekhy doesn’t borrow liberally from existing religions and even realistic existing schisms and splits, but that’s an intentional choice, too. This is the trick. I was talking with somebody recently and we were talking about the depiction of war and soldiery and how tricky that can be, trying not to valorize and romanticize war and I think this is true of everything you include as a story. As a storyteller, you have to take into account the baggage that people are going to bring to things if you choose to include something in the narrative, whether it’s something mundane or whether it’s something very controversial and loaded. All of which is to say we had to invent new religions. These could not be regular religions. But at the same time, everything in Free Planet, it’s not enough just to come up with a religion. Theat religion needs to funnel back into these core considerations and ruminations that are at the heart of Free Planet.

That’s why Teomekhy as a whole, as well as kind of the distinct differences between orthodox and reform Teomekhy there is this big question of freedom in terms of free will and our choice and what kind of choices we’re permitted to make or are even capable of making. The Orouran Empire, they have an imperial cult where they worship their leader as a god emperor, but that religion also has its own distinct view on freedom. This isn’t just some wacky made-up religion, these things, out of necessity funnel right back into these larger considerations and that to me is the core of Free Planet. Free Planet is a rumination on freedom and on these big issues. All this other stuff works to prompt that in the readers.

The Future of Free Planet (And It’s Big)

So, issue six is coming up and leads us to a very interesting place. I’m not going to spoil that for people because they need to experience it for themselves. But what are you excited about in future issues?

Sitterson: So, issue six is the climax to our first big arc and it leaves you in kind of a shocking, precarious, intense place. What comes next is something a little bit different. It’s our first interlude. It’s our first Free Planet interlude. It’s going to be two issues. It’s called Expansion Protocols and it’s an opportunity to continue exploring the themes and the core of Free Planet and what Free Planet’s about: freedom, sacrifice, authority, discipline — these core themes. It’s a chance to explore those while further building out the world and the complexity surrounding all these big questions and the way we’re going to do this is they’re the planet Lutheria, which is where the bulk of our action takes place and the planet Lutheria is caught between two massive galactic superpowers, the corporate dominated oligarchy of the Interplanetary Development Alliance and the Meritocratic Autocracy of Orouran Empire.

Our new interlude Expansion Protocols is going to explore the distinct ways in which these two civilizations have expanded throughout the galaxy and this is something that sits at the core of both kind of the questions that readers have around the world and how it functions. How did humanity spread out across the stars, how did humanity find its lost cousins and bring them into the fold and the answers are different depending on whether we’re talking about alliance or Orouran empire.

We’ve got two issues. The first [with artist Ilias Kyriazis] is going to explore Alliance and how it subsumed and co-opted individual members of the human diaspora into this larger unit and it does that through the story of one planet on which multiple arcs of humanity landed and two distinct civilizations arose leading to millennia of heated warfare and hostility until the Alliance arrives.

Then, issue eight, we’re going to be exploring the mechanisms by which the Orouran Empire has conquered other planets and it’s an entirely different process than what the Alliance does as you can probably imagine from what we know of these two civilizations. This one is about a single space marine dropped on an unexplored planet and expected to conquer to the best of his abilities and it’s drawn by my Beef Bros co-creator, Tyrell Cannon, after which Jed comes roaring back with a vengeance for issue nine. Seven is in December and eight is in January. Nine hits in February.

Free Planet #6 goes on sale October 8th.

What do you think? Leave a comment below and join the conversation now in the ComicBook Forum!