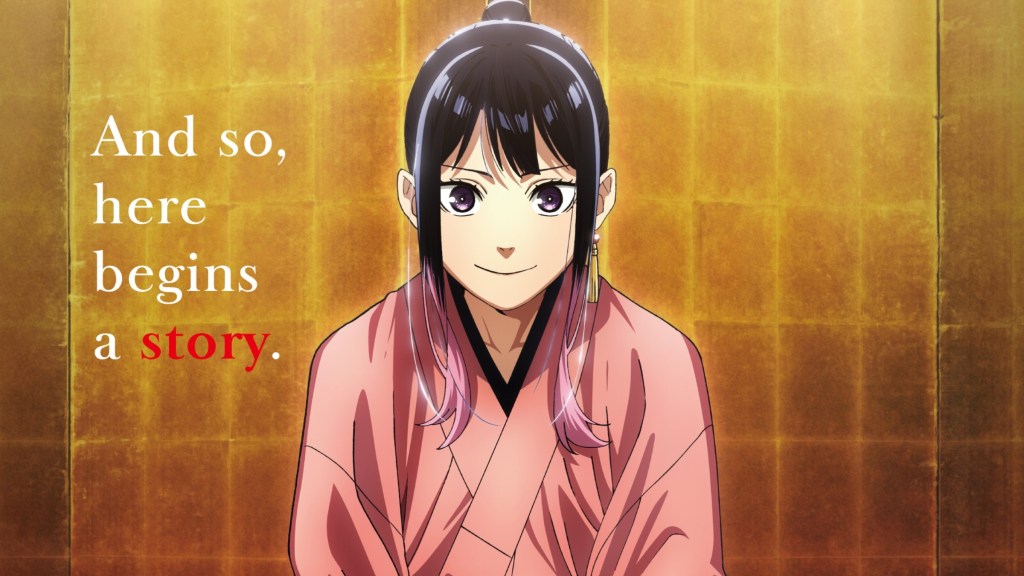

In the traditional form of comedic storytelling, Rakugo, the storyteller, called a rakugoka, sits on a stage to deliver a monologue with a paper fan and a small cloth as their only props. In portraying multiple characters within the story, the rakugoka must do so through changes in voice, facial expressions, onomatopoeia, and subtle body movements. It’s basically a traditional form of stand-up comedy (or sit-down comedy?). With the limitations that the form of entertainment already involves, it would seem as though it would be even more limiting, if not nigh impossible, to attempt to translate such into, say, a printed work like manga. Yet that’s exactly what Akane-banashi accomplishes, and successfully.

Videos by ComicBook.com

Written by Yuki Suenaga and illustrated by Takamasa Moue, the ongoing 17-volume manga series may seem limiting to the storytelling medium, but the manga medium of illustration actually gives a wider range of creative liberties than one would think, implementing the use of illustrated techniques such as varying layouts, stylization, angles, certain crescendos and highlights, backgrounds, and other subtle distinctions to bridge the gap. And with the manga series having received such high praise, it’s no wonder it’s also receiving an anime adaptation. As a series that’s sure to stoke curiosity about the profession worldwide, it’s reminiscent of another series that had done similarly with another traditional form of entertainment.

A Series on Traditional Storytelling

Rakugo is ultimately an art form that takes years for a rakugoka, its practitioner, to master and hopefully ascend from the zenza apprentice status, past the futatsume semi-pro status, to the top rank of shinuchi. Having been enamored since she was little with her father’s ingenious rakugo style, Akane Ousaki looks up to her father, Tohru’s performances. But when he’s faced with the last hurdle to reach the rank of shinuchi, though his exam performance in front of senior rakugo master Issho Arakawa is passionate, it not only gets Tohru expelled from the rakugo school, but it also pushes him to give up on rakugo entirely and settle for a regular job. Seeking vengeance for her father’s unjust disillusionment, Akane begs Tohru’s former rakugo master, Shiguma Arakawa, to mentor her. Apprehensive at the prospect, Shiguma feels he must test her resolve to follow in her father’s footsteps. The test? Performing in front of an audience.

While the dramedy series may initially seem like a forgettable, boring concept, with depictions of such high-stakes and competitiveness, in the words of TazerLad, it’s actually pretty “shonen as f-ck.” Heck, even Hideaki Anno, creator of Neon Genesis Evangelion, and Eiichiro Oda, creator of One Piece, have both praised and recommended the Akane-banashi manga series. Although the manga series had already successfully translated rakugo into an illustrated medium, audiences are sure to be excited at the prospect of the anime adding music, voice acting, sound effects, movement, and other supplemental effects to enrich the experience even further.

A Series on a Traditional Board Game

And with surreal renditions of each of the characters’ unique brands of storytelling sure to compel audiences’ curiosity to learn more about the traditional entertainment, there had been a certain other anime series in the past that had done similarly. Instead of rakugoka performing on the stage, this series helped stoke the world’s fascination with Go. Akane-banashi is not unlike one other Shonen Jump classic, from Yumi Hotta and the Death Note artist, Takeshi Obata: Hikaru no Go. As a 23-volume 1998 manga and 2001 anime adaptation, Hikaru no Go inspired a new generation of young Go players curious about the classic, incredibly complex board game, thanks to the story’s actually compelling premise.

When Hikaru Shindo stumbles upon an old go board in his grandfather’s attic, after touching it, he hears a mysterious voice as he passes out. He awakens to find that the voice belonged to Fujiwara no Sai, the spirit of an ancient Go instructor for the Japanese Emperor in the Heian Era. As Sai’s transcendental passion allowed his spirit to continue to experience the game, mastering a divine go technique never before achieved became his ultimate goal. And through Hikaru, Sai’s endeavor could possibly finally be realized. Although Hikaru has no interest in board games, he decides to play along under the guidance of Sai. But when Hikaru meets the young Go prodigy Akira Touya, his new rival inspires within him a newfound passion for the game.

Sometimes, such traditions have even evolved with the times, with younger generations putting their own innovative spins on classical practices, such as Rakugo, catering to a wider range of audiences via streaming rather than limiting such an experience to being in-person/in-theater only. As both series feature young protagonists becoming inspired by very old Japanese traditions (Rakugo and Go), like Hikaru no Go had done, Akane-banashi could potentially spark younger generations of today to become inspired once again to become interested in and revitalize such cultural traditions, perhaps even worldwide.

Are you hyped for the anime adaptation of Akane-banashi? Let us know in the comments if you’d also been a Hikaru no Go fan!