I work in construction as my day job. Back in 2013 I was located at a remote campsite in British Columbia for approximately half of the year. Getting from home in the Midwest to the site involved three flights, multiple car rides, and a two and a half hour boat ride that separated the camp from the nearest town. Once you were at work, you were away from home for the next 15 days before receiving a 6 day reprieve. Rinse and repeat. The sights you would see working heavy construction in such a remote region of the world, both natural and manmade, were breathtaking. Mechanical achievements were accompanied by some of the most serene and untouched wildlife you could imagine, like watching bear cubs play less than 200 meters from where you ate each day. It was also an intensely isolating (and often depressing) experience. This sort of work generates a unique culture of people who thrive outside of society spending long stints away from family, friends, and even the internet. There’s really no way to understand what it’s like to work on a camp job without having worked on a camp job.

Videos by ComicBook.com

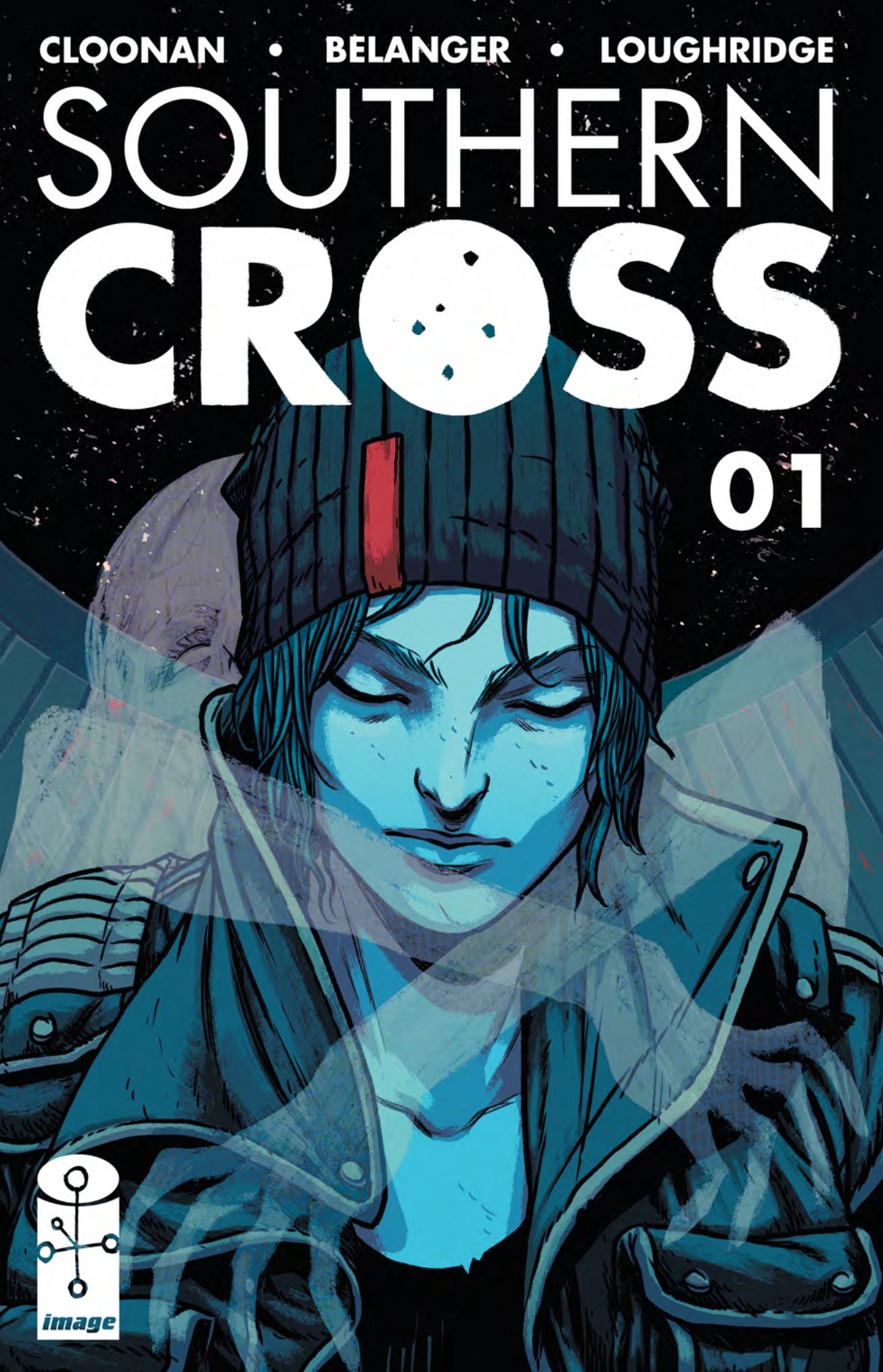

That’s what I find so impressive about Southern Cross #1; it captures so many unique elements of that experience so well. It’s something I’ve lived, and Becky Cloonan, Andy Belanger, and Lee Loughridge have translated it to the comics page seamlessly. If I had to explain to someone what it was like for me to leave for work back in 2013, I’d consider handing them this comic.

Southern Cross #1 opens on Alex Braith boarding the tanker Southern Cross in order to take the six day journey to a moon colony drilling for oil. Unlike all of her fellow passengers, she is not leaving earth for work, but to retrieve the remains of her sister who passed away under mysterious circumstances. The Southern Cross is filled with miners, crew men, and other wayfarers, but the culture aboard the ship and the ship itself are alien to Alex leaving her stranded and looking for answers.

The setting of Southern Cross helps to highlight the emotional chill and isolation of Alex’s situation. It is a beautiful piece of symmetry where a character’s internal and external circumstances inform one another providing insight without a need for obvious exposition. That’s important because Alex is not a forthcoming character. She is shown to be solitary and distrustful, so any overt revelations of her past or suspicions would be out of character. Cloonan recognizes this and exploits opportunities to show us who Alex is, rather than tell us. Her internal narration is kept to a minimum and only drops hints at the larger picture, hiding facts from the supposedly omniscient perspective we are presented with inside of her head.

It’s in Belanger’s art that Alex and this world is truly revealed though. His line work is tight and densely clustered. Alex and her fellow passengers are given understated expressions, clear enough to read, but never too open or revealing. Even when Alex is interacting with others, this results in relationships that are closed and impersonal like something pulled from a poker game. The tone and experience of being trapped on a journey far from home and anything familiar is summoned in all of its stark beauty here.

The manner in which Belanger composes his pages pulls readers down through the guts of the ship and across the page. Tightly woven 8 and 9 panel grids are structured like steel clusters crunching moments together in an almost claustrophobic construction. In one page, he weaves through the ship as a diagram with each connecting room or hallway forming a new panel. It is this tightly plotted layout that reveals the tension and energy present in most pages, forcing the eye forward and denying readers any chance to catch their breath.

Belanger is at his best in tight quarters and when focused on interpersonal dynamics, but he falters when the scope widens. The tight compositions that make traveling through the oil tanker so effective are exactly what undermine panels depicting the enormous ship or objects in space. These long panels appear too flattened to be part of something as enormous as space. The scale may be correct, but there is no distant horizon to pull the eye and stun the reader. There is no awe contained in Belanger’s enormous splash panels, only the sort of scope that would make awe seem to be a natural response. The most inventive panels that Belanger makes work are those that occur in the engine room, infusing the industrial setting with an odd, twisted beauty.

Lee Loughridge’s colors capture the essential feeling and intent of each of Belanger’s panels, whether they are within the ship or set in the vastness of space. He favors a cold palette with plenty of blues that reflect both the tone of the story and reality of the setting. Even Loughridge’s reds are washed out to a pale rose tint making it clear that no warmth has made it on board of the Southern Cross. It’s the sort of coloring that will send shivers down your spine after reading only a few pages and it does a tremendous job of enhancing both Cloonan and Belanger’s work.

The combined effect is the creation of a mood that is absolute. You are brought into Alex’s experience and the strange voyage she has chosen to embark upon by force. There are no escape hatches or parachutes here. It’s a long flight out to a distant world dominated by industry far from anything that resembles home. The act of reading Southern Cross #1 brings about feelings of isolation and uncomfortable, alien experiences. There is beauty to be found on these pages, but it comes at a cost.

There are elements of Southern Cross #1 that didn’t strike me so positively. The plot of the first issue is so eerily similar to that of Roche Limit as to feel redundant and Belanger’s splash panels never seem to fulfill their promise, but those flaws cannot detract from the debut’s greatest strength. Southern Cross #1 composes the mood and experience of isolation through narration, composition, and colors. It summons an experience with which I am deeply familiar with an honesty that I find to be stunning. Somehow, Cloonan, Belanger, and Loughridge have brought that experience to life on the comics page, and for that they should be applauded.

Grade: B

Southern Cross #1 was published by Image Comics on March 11, 2015.