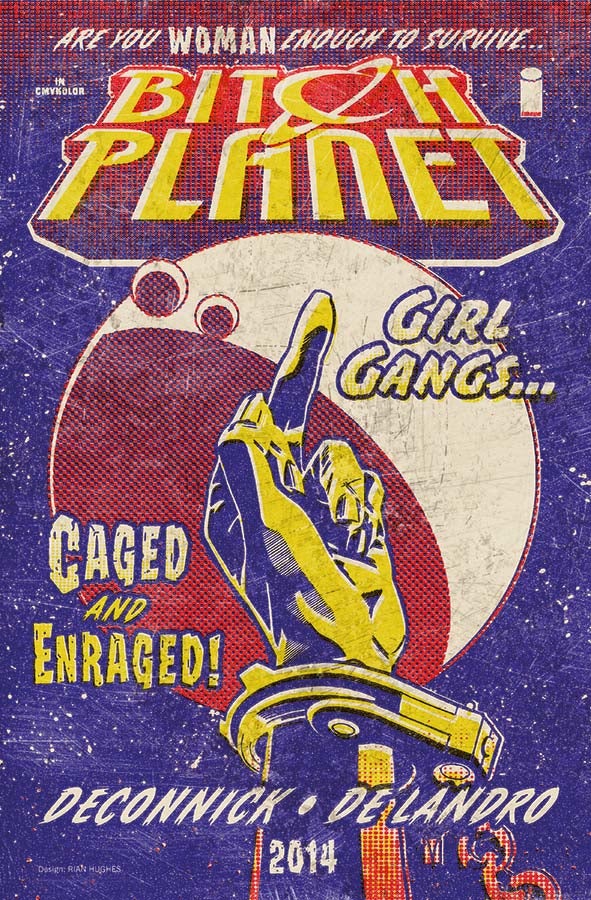

Kelly Sue DeConnick and Valentine De Landro’s new series Bitch Planet yearns to take a more feminist approach to the “women in prison” genre films of the 1970s. The premise is certainly a solid opportunity to do so: the story is set in a dystopian future dominated by an authoritative government capable of banishing unsubmissive women to a prison planet. The first issue focuses on a new batch of arrivals composed of killers, “radicals”, and one volunteer.

Videos by ComicBook.com

New releases from Image Comics have begun to generate their own wave of hype. The publisher consistently cultivates great talent and comics; they have released many of the best new ongoing series of 2014. DeConnick brings her own fanbase to the table as well. She’s beloved for her work on both Captain Marvel and Pretty Deadly. De Landro’s art speaks for itself and, if nothing else, Bitch Planet will help bring attention to his excellent craft. There’s no doubt that this series, first announced at Image Expo in January 2014, will continue to receive a good deal of attention and excitement. But is it deserved?

Based on this issue, no.

Now, this is only the initial taste of an ongoing series, so there’s obviously a lot of room for DeConnick and De Landro to grow and evolve, but this debut is often troublesome. It’s clear that the creative team knows what they want to achieve. The ideas and sentiments are present, but their effectiveness is debatable.

Bitch Planet wants to subvert its genre in order to make a statement about feminism and gender roles. That focus comes through in the premise and plot points of the first issue. It’s obvious that the comic sympathizes with women and their place in this monstrous future. There is plenty of overt conflict development that conveys this, but it’s present in the details as well. In the dense first page, De Landro populates futuristic city streets with advertisements bearing messages focused on weight loss and “fixing” women. All of the ads are directed at women in a way that treats them like objects and demands their subservience. This exaggeration (but still realistic) turn on modern advertising displays how this world views and treats its women.

The political specifics of this future are uncertain, but also unnecessary. De Landro and DeConnick provide enough flavor in the opening pages to show how the system works. Whatever the future of government is, it clearly elevates the needs of men over women. It’s a world where feminism appears to be forgotten or outlawed and the law of the day is patriarchy.

Unfortunately, Bitch Planet #1 tends to focus on the monstrosity of those in control rather than the humanity of the women. Although the first issue presents the series’ conceit and introduces a handful of characters, it also includes a self-contained story, an immorality play. Moving between panels set on Earth and in space, DeConnick tells a story with two sides and a cruel twist ending. It’s a tightly plotted page that serves as a nice centerpiece to the issue. De Landro’s compositions are key to its effectiveness. He navigates between different points of view and moments in time connecting half-finished sentences from multiple speakers. It’s a clever idea, but one that relies on absolutely clarity in execution, which De Landro achieves even if there is some confusion in the dialogue.

This centerpiece serves to display the lopsided balance of power between men and women, but never actually humanizes the woman in trouble. She is a middle-aged, white woman convinced that she does not belong on Bitch Planet. The miscarriage of justice she faces is certainly worthy of sympathy, but her characteristics are scared and terrified. She is a woman defined not by her own personality, but by the injustice that has been done to her and her emotional response to her plight. Her role in the story serves to define the antagonist, rather than humanize the victim.

In the first issue, only three women are given focus to set them apart from the others. The first is the woman who has been sent to Bitch Planet by no fault of her own. The other two are black women characterized primarily by their appearance. One is morbidly obese and proud of this fact, bearing a tattoo that proclaims her to be “Born Big”, while the other is well-defined by her muscles and a scar as someone very capable in a fight. Although there is sympathy to be drawn from their situation, they are one dimensional as human beings just like the victim above. There’s no hook to be found in these characters besides the mystery of where they come from and why they are here.

De Landro does a great job of illustrating these women though. There is ample nudity, playing up the inspiration of exploitation film, in the first half of the comic. Lines of women are marched about wet and weary. De Landro walks a very careful line and never objectifies their forms. They are presented as human beings with realistically drawn bodies and body language that reflect their situation. There is nothing exaggerated in their proportions and no person is posed to emphasize their sex. Nothing about the nudity in Bitch Planet is sexual; it is a graphic, but normalized part of this terrible world.

This humanization is balanced by the hyper-sexualized artificial intelligence that runs Bitch Planet. A bright pink hologram that can take on multiple forms, she is all long legs and big lips. Her waist is sewn in by a corset pushing butt and breasts out in an uncomfortable display. Cris Peter’s colors define her as an unnatural construct, fitting naturally into the pulpy atmosphere of the comic as well. De Landro plays up the difference between this ideal of superhero comics and the real women that populate the rest of the page. The sexualized computer is a tool of the prison planet and one that aids in imprisoning and hurting the women, a none-too-subtle metaphor about body image.

Bitch Planet isn’t devoid of problems with body image, though. There’s a distinct lack of diversity in body type. In the opening pages when dozens of women can be seen naked, it becomes obvious that they would all be considered within the normal range or possibly underweight by the body mass index. Waists are either composed of straight lines or highlight an hourglass figure. The only woman who could be considered overweight is beyond morbidly obese. Her weight is her defining characteristic and she is drawn in such a way that her mass is intentionally repulsive. There’s an unintentional element of fat shaming in this comic, where women are depicted as either normal or grossly fat. No middle ground can be found between the extremes.

Racial tension is another disturbing element of the comic. Of the three women who are given some sort of personality in this first issue, two are black and one is white. The white woman is portrayed as an innocent victim. The two black women are aggressive and angry. They start fights and respond much more naturally to their new incarcerated surroundings. In the context of the first issue, it reads as if the black women fit into the prison population more naturally. Even if this is intentionally included as part of the exploitation genre, it’s worrying at the least.

It’s clear that Bitch Planet seeks to invert the exploitation genre in order to tell a story steeped in feminist ideals, but it falters in its first issue. Although it’s clear that women are being exploited by a patriarchal society, the women in this issue are never given an opportunity to define themselves outside of their victimhood. Furthermore, issues of race and body image have to be carefully considered as well. Intentional or not, this issue perpetuates stereotypes of race and weight through its imagery of the prison population. There is promise to be found in this premise, but the execution is lacking here. Bitch Planet #1 doesn’t achieve its goal of being something fresh and bold, but only serves to reinforce the problems currently facing women in comics and society as a whole.

Grade: B-