What are the colors of belief? What is the hue of orthodoxy? Lorenzo de Felici’s Kroma #1 wades into these questions by contrasting life within the Pale City, humanity’s last enclave, against the iridescent wilds that surround it. In the afterward of the issue, de Felici explains that he originally conceived of the idea for Kroma years ago, while working as a colorist on Italian comics. His skills as a colorist are essential to Kroma’s success, as it not only utilizes color as storytelling tool, but is about color itself and how colors map onto our experiences throughout life.

Videos by ComicBook.com

In that same afterward, de Felici explains that he wanted to avoid simply using color as a metaphor the way films often do and make color a presence within the story, instead. While he does that, there’s no escaping the familiar metaphorical value of color contrast. By opening the issue with pages featuring the colorful wilds of Kroma‘s world that practically shimmer, he creates a sense of loss when the story instead takes root within the colorless walls of the Pale City, a yearning for the brightness of those earlier pages.

And it’s an important distinction, and a credit to de Felici’s skill, that the city does feel “colorless.” Not black-and-white, or grey, but without color, which turns out to be central to the belief structure that has allowed this final bastion of mankind to survive. But at what cost?

The Pale City’s denizens don’t simply go without color, but hate, fear, and loathe it. It’s there in the face of a young boy when a colorful bird falls dead in front of him. But despite the façade of colorlessness, there is still red blood running through their veins. As the Makavi, the society’s priestly class, explain, this is a reminder of the greed that ended the world as their ancestors knew it, the greed that still exists within them and that threatens to escape when they gaze too intently on the blue of the sky or the green of the trees outside the city’s walls. It is a loathing for themselves, drenched in the unearned guilt that colors many of our experiences with religion.

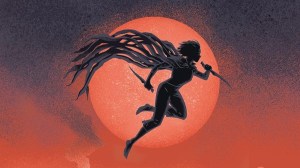

It’s what makes Kroma, the young girl kept in the city’s high tower, the perfect sin-eater for this society. For generations, those who lived within the Pale City snuffed out the lives of infants who had anything but black hair and dark eyes, until no such variety remained in their society. But through random mutation, or perhaps a lack of diversity in the remaining genetic pool, Kroma has heterochromia iridum, making one of her eyes the blue of the tempting sky, and the other the green of those dangerous trees.

But her existence is a secret. She’s only allowed out for ritual beatings, cast as a new threat sent by the King of Colors to infiltrate the Pale City. Dressed as a monster with eyes that can drive you insane, no one but the priests know her true nature until Zet, a Makavi initiate, sees her eyes for himself and, for the first time, begins to openly question what he’s been taught to believe.

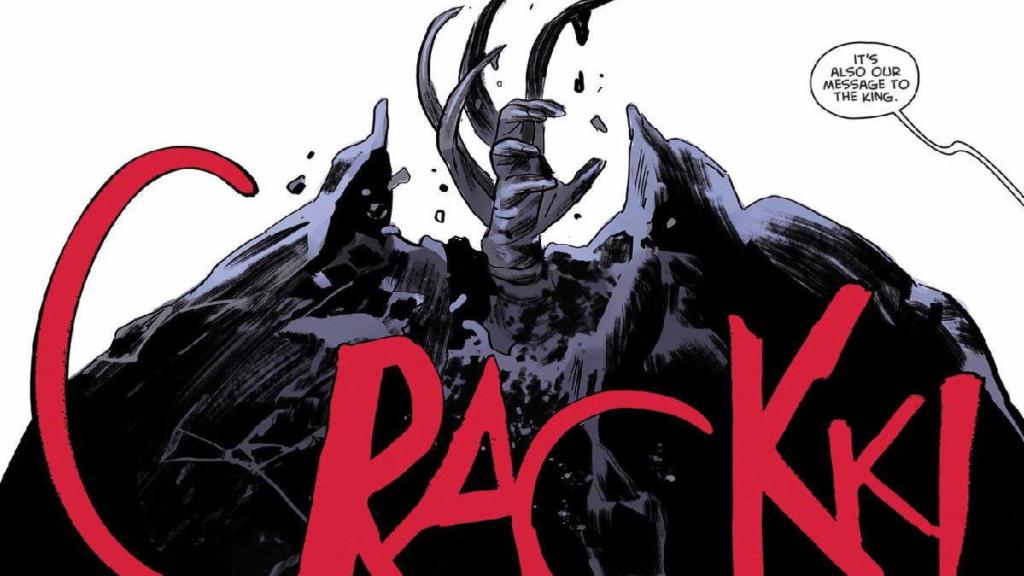

The scaffolding holding all of this world-building up is a nuanced consideration of religious orthodoxy. At every turn, the Makavi cast the new as the enemy. Humanity’s great betrayal was the attempt by a scientist to create a new color. Kroma’s eyes are something new, or at least unseen in generations. There are examples of the faithful using logic based on flawed assumptions to justify horrors, and one of the Makavi speaks without shame on how their job is to use the fear of the faithful to keep to the old ways. “It is right” is a repeated mantra, as in “it is right that we should be forced to live in this meager place” or “it is right that others should do me harm,” showing how guilt is mingled into their core beliefs, making the populace all the more pliable. And yet, the giant lizard beasts that supposedly fed on human blood do exist outside of the Pale City, and they do seem blind to black and white, suggesting that these traditions, though possibly warped now, hold roots in the necessities of survival.

De Felici, in his afterward, discusses some anthropological theories about color and life, how we begin in the blackness of the womb, progress and gain new colors from red to blue to green, and eventually die heading toward a white light. If this is taken as true, it’s easy to see the emptiness of the Pale City’s existence. There is the black and the white of living and dying, of surviving, but the colors of the other experiences are absent. Though she’s lived in a tower for presumably her entire life, the irises of Kroma’s eyes make her seem more fully realized on the page than the often simplified dotted eyes of the others living in the Pale City. And yet Kroma has never seen herself or her eyes. She knows only the colors outside her cell window and knows herself only as what others have told her she is: a monster.

Zet sees something new in those eyes, something that makes the sky and the trees less threatening, something that makes him feel assured enough to challenge the High Makavi rhetorically. The Makavi manage fear, so it should be no surprise that those without fear should become unmanageable.

It’s unclear where de Felici will take Kroma in future issues as the story’s inciting incident only occurs on this issue’s final page. While readers will have to wait for another issue to see the main thrust of the plot revealed (one would assume), Kroma #1 stands tall as a solidly constructed feat of worldbuilding, and a considered musing on the colors of life, primarily those we fear and those of which we deprive ourselves and others.

Published by Image Comics

On November 16, 2022

Written by Lorenzo de Felici

Art by Lorenzo de Felici

Colors by Lorenzo de Felici

Letters by Rus Wooton

Cover by Lorenzo de Felici