Daggerheart, the new longform fantasy campaign-style tabletop RPG by Critical Role’s Darrington Press, is a surprising blend of vasty different playstyles that somehow blend together for a very fun experience. This weekend at Gen Con, ComicBook.com had the chance to run through basic character creation and a play session with Spenser Starke, the lead designer of Daggerheart, with Critical Role cast member (and company CEO) Travis Willingham at the table. When Daggerheart was first announced earlier this year, many players wondered whether it was intended to be a competitor to Dungeons & Dragons or could potentially replace D&D as the game used by Critical Role to tell their stories in their main show. From what we experienced over the four hour game session, Daggerheart may not be a direct competitor to D&D, but it has a lot of potential to be a major competitor when its released in the future.

Videos by ComicBook.com

Before diving in too deep into Daggerheart, we will note that it is an original game that incorporates concepts and mechanics from a number of different tabletop RPGs. The core system is built from the ground up, but Starke noted during our playthrough that the game drew inspiration from several sources and existing games. There were elements similar to mechanics found in at least a half-dozen different games, but it feels unfair to say that Daggerheart is a rift or a derivative of any of them. Unlike Candela Obscura (and assumably the Illuminated Worlds game system), Daggerheart isn’t a take on or “powered by” a specific game – it instead uses inspiration from a number of different sources as the foundation for a new experience.

The heart of Daggerheart is a new 2d12-driven check system. Players make rolls using two different colored d12s, with one called the “Hope” dice and the other being the “Fear” dice. When a player makes a check, they call out the result and note whether it’s made with Fear or with Hope, depending on which dice shows a higher number. So, a 9 on the Hope dice and a 7 on the Fear dice is a “16 With Hope,” while a 7 on the Hope dice and 9 on the Fear dice is a “16 With Fear.” Advantage and disadvantage were factored in with the use of a d6. A roll with advantage added the d6 to the result, while disadvantage subtracted the d6. Doubles on the d12s results in a critical success, which is a success with no negative consequence and usually a narrative bonus on the result.

Hope and fear drive some of the basic narrative flow of the game. A roll made with hope typically has a positive consequence, even when the check is a failure. In combat, an attack roll made with hope means that the players retain initiative and a player character gets to go next. Additionally, rolls with Hope generate a Hope resource, which can be used to either fuel various player abilities or aid another player’s roll (or their own roll.) A roll with Fear hands initiative back to the enemy characters and often comes with some sort of narrative consequence that the Game Master warns players about in advance. For instance, my Rogue character made an Agility check to run past one enemy to attack a more vulnerable foe. The roll was made with Fear, so the enemy I ran by was able to attack me as I sprinted. Outside of combat, Hope and Fear serve as a way to guide the narrative, similar to “Yes And” systems found in more indie-style TTRPGs.

When creating a character, players have four points to spend across 6 different stats, which include Strength, Agility, Precision, Presence, Intuition, and Knowledge. Different weapons and abilities are powered by different resources and players add their corresponding score to an attack roll or check. For instance, my Rogue had an innate Spellcasting ability that allowed me to summon a cloud of darkness if I made a successful Agility roll with a pre-set DC. When asking whether a character could do something or had knowledge about something, it was up to the GM to decide what ability a player rolled with and what the results could potentially be. I’ll note that player characters often had abilities that gave them advantage or allowed them to spend Hope or take a point of Stress to gain advantage on roleplaying and social rolls, which indicated that sessions aren’t necessarily driven by combat.

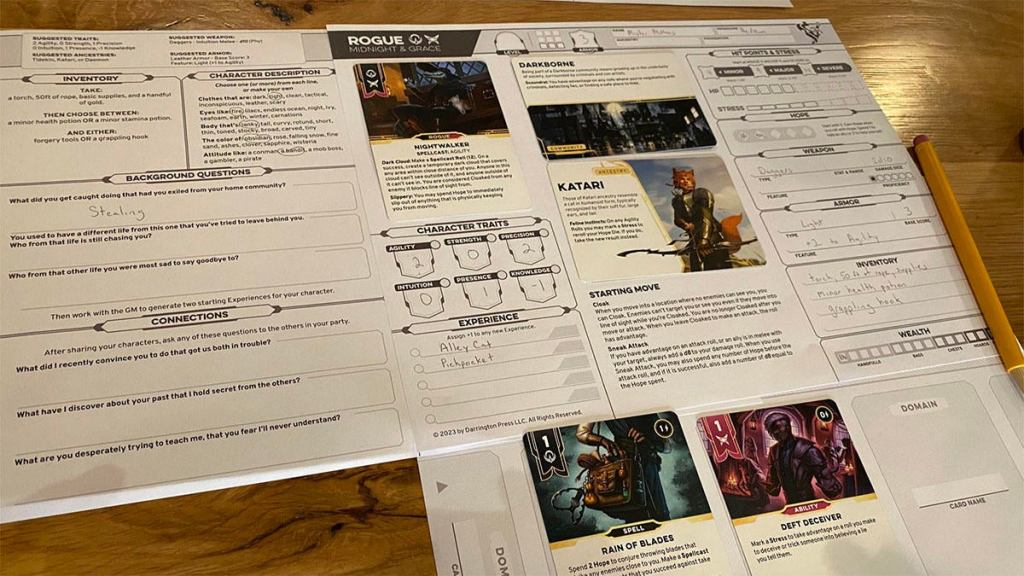

One of the more intriguing and unique bits of Daggerheart is the card-based system that players use to choose their character’s abilities. Each of the game’s classes (which contain a mix of traditional fantasy classes and new classes like Guardian or Seraph) have certain core abilities. However, each class has at least two options similar to subclasses that come with an additional unique ability. Also, each class has two “domains” with different powers represented via different cards. Players choose two abilities from their class’s two domains when they start the game and choose additional abilities when they level up. A player has no more than five domain abilities active at once, with other abilities going into a Vault and can be swapped out during either downtime or some kind of rest. Ancestries and communities are also represented by cards that are placed on top of a player’s character sheet. Each ancestry and community background also comes with some kind of ability or trait spelled out on the card, ranging from advantage on certain kinds of checks to a mechanical benefit like extra armor.

The result of character creation in Daggerheart is a three page character sheet with several cards placed in different slots and certain pages tucked halfway underneath the “main” character sheet. However, all of a character’s abilities and stats (including spells, weapon abilities, and more) are represented on the page and there’s no need to refer back to a rulebook for clarity on a specific ability, spell, or rule. Interestingly, Daggerheart seems be much more geared towards having a physical character sheet in front of players, at least judging from the use of the cards to inform character creation.

Another interesting system is how HP and armor are used in the game. Players start off with 6 hit points and 5 stress, along with a set of three damage threshold numbers. When a player or creature successfully makes an attack, they roll damage dice, ranging in size from a d6 to multiple d20s. If the result of the damage dice roll is below a player’s first damage threshold number, they take a point of stress. If the result is between the first and second damage threshold, they take minor damage resulting in losing 1 point of HP. Similarly, a result between the second and third damage threshold results in major damage for 2 points of HP, while exceeding the third damage threshold results in severe damage for 3 points of HP. Each player also has an armor score and three armor slots or resources – when they take damage, they can reduce the damage roll by the number of their armor score. So, if a creatures rolls a 15 on a damage roll, a player with an Armor score of 5 can reduce that damage roll to a 10, potentially turning a severe damage into a major damage, but at the cost of one of their Armor resources. (Armor can be repaired as a Short Rest activity.)

Finally, we should mention the Death mechanic of Daggerheart, which is a lot more meaningful than what we’ve seen in games like Dungeons & Dragons. When a player runs out of Hit Points, they have three options – they can choose to die in a blaze in glory with an automatic critical success on their final action, they can choose to become scarred and permanently remove one of their hope slots to recover, or they can risk it all by rolling their hope and fear dice and letting the dice determine their fate. If the hope dice is higher, their character recovers, but if the fear dice is higher they die. Starke mentioned that there’s only one resurrection spell in Daggerheart that is an one-off ability, so it seems death will have a higher impact and stakes than in other fantasy TTRPG games.

From a narrative standpoint, Daggerheart seems to be much more of a collaboration between player and GM than something like Dungeons & Dragons. For our game, Starke went around the table and asked the players questions about the city we started with, asking us to fill out the details of the town. We chose the name of the starting town, its defining features, and what tragedy recently befell it. We also defined the quest we were to go on and what kind of connections this quest had to each player. This didn’t just occur at the beginning of the play session either, Starke asked us to describe the monsters we were fighting as they arrived on the battlefield, the major NPCs we interacted with, and even the architecture of the towns. For our table at least, we were able to riff off of each other’s suggestions to organically form an emerging narrative and story, filled with carapace-armored Horde ruffians and a bearded wyvern with fire breathe and an earwig-esque pincer tail.

Making the GM and players equal partners in the storytelling seems to be a central ethos in Daggerheart. Starke mentioned the possibility of providing a blank map with a few general features to the players, with the players naming the towns and notable points of interest and letting them build the world that they are about to explore in. There’s certainly room for a traditional D&D-type experience where the GM does all the world building, but there’s also room for something akin to Dungeon World where the game is much more freeform and concerned with letting the world grow as the story moves. While I think this kind of collaborative worldbuilding can occasionally result in Mad Libs kinds of shenanigans, a good party of players who are aligned in what kind of stories they want to tell will find this narrative structure much more engaging from the get out. A world that the players help build from the onset is a world where there’s no needed buy in from players to make the game a success – Daggerheart understands that and seems to actively encourage that.

Obviously, Daggerheart is still in the active playtesting phase and it’s clear that the game is trying to balance and tune a lot of different features before it’s ready for sale. However, I thought it was interesting how the game encourages power gaming (a lot of player abilities have synergies that can ramp up to do a LOT of damage or provide other awesome moments) without being too focused on optimal builds and seems to be able to pivot between narrative freeform and more structured games with built-in rails. More importantly, Daggerheart seems to be a fully fleshed out game system instead of just a game built for a specific world, which I think was one of the major concerns of the game when it was announced.

Although Daggerheart is still a work in progress, I came away very impressed and intrigued by the new system. I genuinely think that Darrington Press has a hit on their hands. It would be premature to call Daggerheart a “D&D killer” but I do think it can present a fun alternative for folks wanting a traditional fantasy TTRPG experience, especially if they don’t want to read a 500-page rulebook to understand the game. There’s a really cool balance between crunch and narrative freedom that Daggerheart offers and the game seemed poised to make a big splash when it comes out in the next year or so.