Yesterday, Dungeons & Dragons announced plans to “update” its Open Gaming License as it prepares to move to a new edition. For months, third-party Dungeons & Dragons content creators have speculated about how Wizards of the Coast and Hasbro would approach the use of the Open Gaming License (OGL) for creating third-party content based on the upcoming new edition of Dungeons & Dragons. There was speculation that One D&D would not utilize the OGL for One D&D in favor of all third-party compatible content being published via the DM’s Guild or another similar service under control by Wizards of the Coast, thus giving Wizards a cut on all third party content made for One D&D. However, Wizards released a statement announcing an “update” to the existing OGL, which would require an opt-in from third-party publishers and would require creators who use this OGL to report revenue if they made more than $50,000 and to pay royalties if they made more than $750,000.

Videos by ComicBook.com

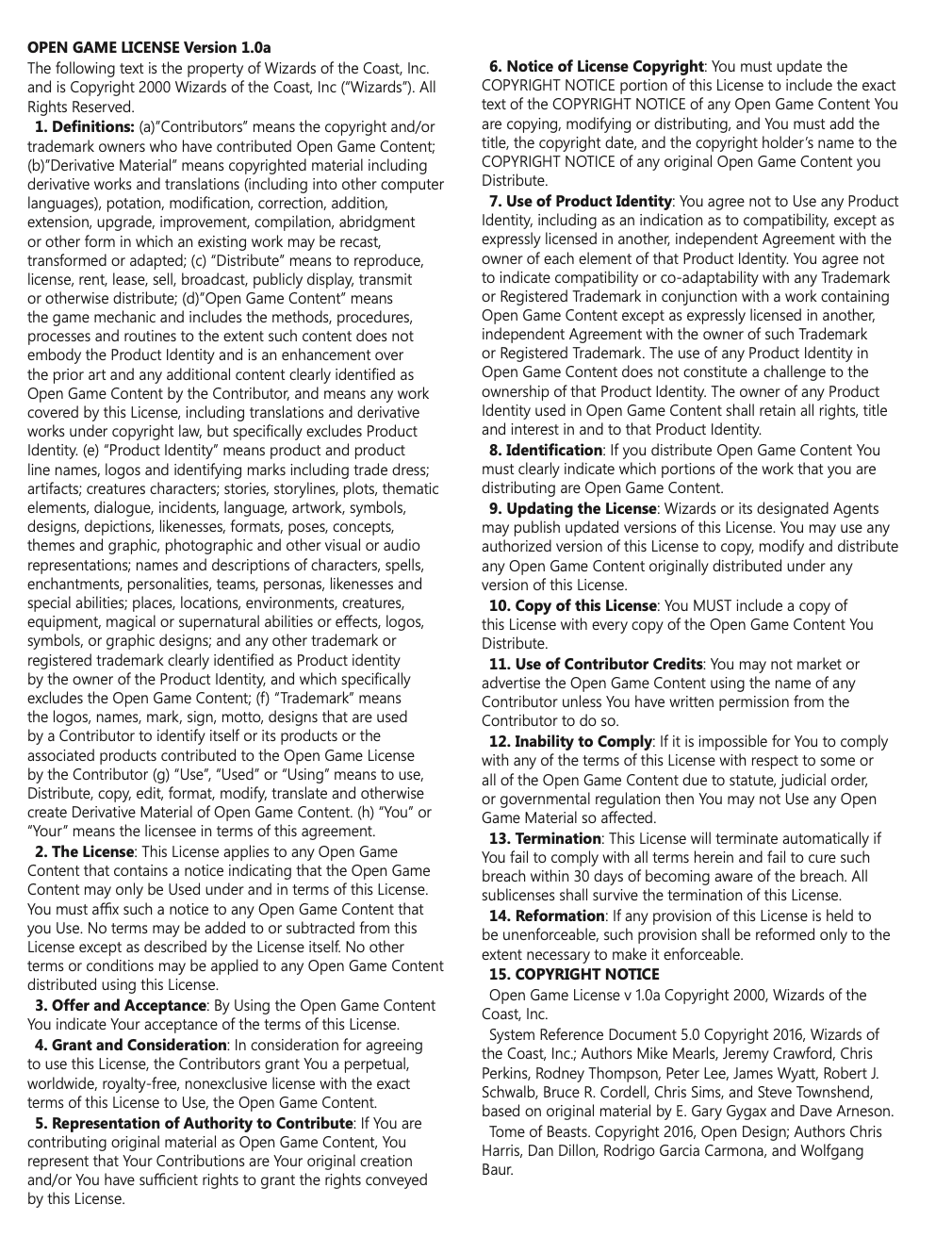

Understanding the nuances of the OGL is complicated, but the impact that the current OGL has on the overall D&D ecosystem is actually very easy to see. If you’ve ever backed a Kickstarter for a 5E adventure or a 5E-compatible rulebook, that book likely has a copy of the OGL 1.0a printed on the last page. For instance, here’s a copy of the OGL 1.0a found in Kobold Press’s Tome of Beasts.

While the OGL or the accompanying System Reference Document (SRD) isn’t something the average D&D player is likely to be aware of, changes to how Wizards of the Coast uses the OGL in conjunction with the new edition will likely impact players who enjoy purchasing non-Wizards of the Coast published D&D material.

Is the Current OGL Going Away or Being Edited?

The short answer – no. The original OGL was created in 2000 and grants anyone who uses it a “perpetual” license to the Open Game License as defined by a System Reference Document (SRD). Creators can use 5E rules and mechanics under the OGL 1.0a, which comes with an accompanying SRD for 5E. The OGL 1.0a cannot be revoked or changed, which means that creators can continue to make 5E compatible work without having to opt into a new OGL, report their revenue, or pay royalties. Additionally, publishers like Paizo can also use the OGL 1.0a to publish their own game systems that utilize some D&D mechanics but not others.

We will add that those who use the OGL 1.0a (or the new OGL 1.1) aren’t technically publishing Dungeons & Dragons material – Dungeons & Dragons is protected under copyright and the actual name “Dungeons & Dragons” can’t be printed by third party publishers without permission. All work published under the OGL 1.0a (or any OGL) is simply compatible with the SRD used in the OGL. That’s why third-party published material can’t use certain monsters like beholders or mind flayers, reference the Forgotten Realms, or even state that their book is compatible with “Dungeons & Dragons.” Most publishers get around that by referring to Dungeons & Dragons as “the first role-playing game” or “the greatest roleplaying game” in their work.

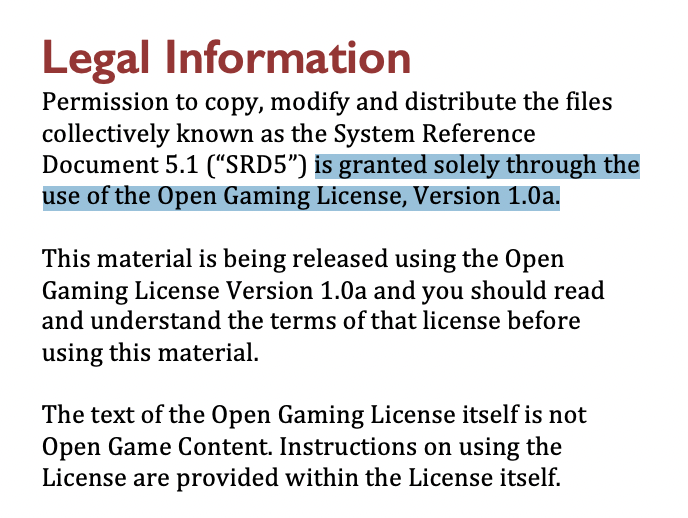

While Wizards states that they are “updating” the OGL to 1.1, they are technically releasing a new OGL with updated language and a new accompanying SRD. Publishers can choose to continue to use the OGL 1.0a, but their material won’t be able to use any One D&D game mechanics that aren’t present in the SRD 5E document. So, if Wizards makes a change to how Critical Hits work, a publisher couldn’t reference that in a work published under the OGL 1.0a unless Wizards updates the SRD5 document or specifically designates a new SRD document as able to be used with the OGL 1.0a. You can see below that the SRD5 is explicitly only allowed to be used by publications that utilize the OGL 1.0a (highlight mine).

What Does OGL 1.1 Do?

We haven’t seen the text of OGL 1.1, so we can’t be 100% sure what it says or doesn’t say. However, Wizards of the Coast noted that the OGL 1.1 will only be applicable to books and “static electronic files” such as PDFs. Wizards notes that the OGL 1.1 will prevent a company from publishing a D&D NTF. It will also prevent a video game publisher from making a game using D&D rules without a separate license. We’ll note that Solasta: Crown of the Magister used 5E rules and was published under the SRD 5.1, but its maker specifically noted they had received a license to use the 5E SRD for their game.

Interestingly, the OGL 1.1 could prevent websites from publishing free share-alike context except as a PDF. It will also prevent third-party publishers from releasing apps made to improve the D&D play experience without a separate license from Wizards of the Coast.

Wizards notes that the new OGL won’t impact existing VTT services like Roll 20, who have separate agreements and licenses with Wizards of the Coast.

How Will Royalties in the OGL 1.1 Work?

One of the major changes the OGL 1.1 is adding a reporting and royalties element for commercial publishers. Creators who are planning to sell their work that will be published under the 1.1 will need to report to Wizards of the Coast what they plan to sell, report their revenue to Wizards of the Coast (if they make more than $50,000 in revenue on OGL 1.1 material), and pay royalties to Wizards of the Coast if they make more than $750,000 in revenue on OGL 1.1 material.

In their statement explaining the new OGL, Wizards says that less than 20 “creators” will have to pay royalties on OGL 1.1 work, although those “creators” likely include publishers like Kobold Press, MCDM, Critical Role, and Ghostfire Gaming. Each of those publishers employ multiple designers and artists, which helps expand the still very small TTRPG industry.

It’s unclear how the royalties system will work, although most publishers impacted by the additional cost are experienced enough to calculate these costs into their crowdfunding projects or product prices. It could mean that some third-party content could have a higher price, especially if those publishers choose to pass the royalty cost onto the consumer. These royalties won’t go into effect until 2024 and will only impact those who publish under the OGL 1.1.

The OGL and the Future of D&D

Until we see exactly what the OGL 1.1 states, it’s hard to speculate what impact it will have on the overall D&D ecosystem. Dungeons & Dragons grew immensely in popularity over the last decade in part because of the influx of 5E compatible third-party material available for free and for purchase. While Wizards is framing the OGL 1.1 as not impeding most creators, we could potentially see a split in the marketplace as some continue to publish under the OGL 1.0a (knowing that One D&D is supposedly “backwards compatible” with 5E material) while others support the new One D&D using material published under the OGL 1.1.

It’s unlikely that the OGL 1.1 is as disastrous as the Game System License used for 4E material, which directly was incompatible with the original OGL and led to significantly fewer third-party published 4E-compatible material. It seems that Wizards is trying to thread the needle between exerting a bit more control over the flourishing marketplace of D&D compatible third-party publications while still allowing designers to indirectly support D&D by publishing One D&D-compatible material.

Assuming that One D&D is truly “backwards compatible” with 5E, many publishers will be faced with a choice of either using the new OGL and complying with whatever additional steps are required for using it, or simply utilizing the older OGL 1.0a to avoid reporting their revenue or potentially paying royalties. A new OGL and its additional requirements won’t likely impact the large majority of designers who want to create D&D-compatible material for free or for purchase, but it will likely impact larger publishers and designers, including prominent creators who have chosen to make their living writing books compatible with various versions of the game. As stated at the beginning of the article, this likely won’t impact the average D&D fan, but it could change how those outside of Wizards of the Coast choose to support D&D players in the years to come.