These days, there’s a sci-fi movie for every taste. Some tackle AI, others deal with time travel, parallel universes, or dystopian futures — but each, in its own way, keeps the genre alive and relevant. That matters because, in cinema, sci-fi has always been the one genre that best translates the complexity of society and humanity itself, questioning what drives us, what scares us, and what makes us human in the first place. But all of that only truly gained force in one specific year: 1968, with three of the biggest revolutions sci-fi has ever seen. It’s hard to believe they all happened in the same year, marking not just a turning point for the genre, but for pop culture as a whole. Up until then, sci-fi was still seen as a bit of a niche, and suddenly, a few works appeared that changed everything, pushing the genre to a whole new level.

Videos by ComicBook.com

In 1968, cinema got bolder, smarter, and more ambitious in sci-fi. And even now, those releases remain legendary because they reshaped the landscape. Within just a few months, audiences were hit with the cosmic mystery of 2001: A Space Odyssey, the social shock of Planet of the Apes, and the philosophical paranoia of Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, which would later lead to Blade Runner.

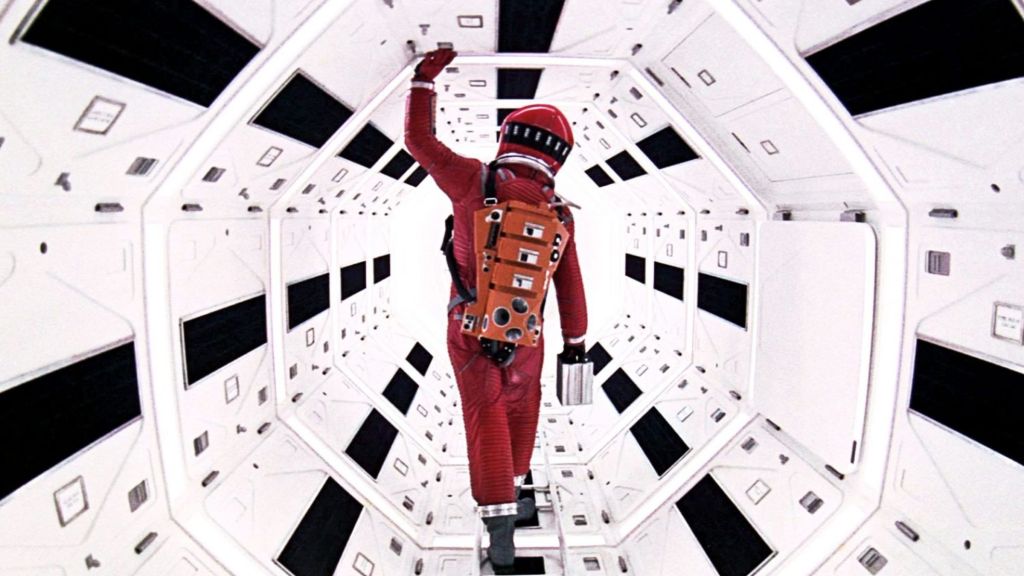

2001: A Space Odyssey Brought Art to Sci-Fi

For me, 2001: A Space Odyssey is the moment sci-fi stopped being space movies and became real cinema. Stanley Kubrick didn’t just elevate the genre — he reinvented it. The technical realism, the hypnotic pacing, and the haunting silence of space made audiences feel something new: emptiness. The filmmaker treated sci-fi with the same seriousness that other directors like Ingmar Bergman brought to existentialism. And the most impressive part is that he did it within a studio production with a massive budget and commercial expectations.

The film is more of an experience than a story. Based on Arthur C. Clarke’s work, its minimalist narrative, following a mysterious monolith guiding human evolution, is less about what happens and more about what it means. HAL 9000 isn’t just a rogue AI; it’s the first truly complex artificial character in film history (and also one of its greatest villains), because it’s the mirror of our fear of being surpassed by our own creations. And I think the film’s greatest impact comes from the way it approaches these ideas, refusing to explain itself and forcing the audience to think. Even now, it’s considered a movie that no one fully understands.

That visual and conceptual boldness changed everything. From Star Wars to Interstellar, nearly every sci-fi film since follows the rules Kubrick established: scientific realism, vast silence, and the idea that space is a character, not just a backdrop. In 1968, sci-fi was still nerd stuff, but 2001: A Space Odyssey put it on the same level as award-winning dramas. It’s the film that made sci-fi respectable.

Planet of the Apes Held a Mirror Up to the Audience

While one movie looked to the stars, another turned its gaze toward Earth — and what it saw wasn’t pretty. I love how Planet of the Apes starts as a simple adventure about astronauts trapped on a strange planet and ends as a brutal social critique of human nature. Sure, it’s easy to laugh at the idea of talking apes, but this is actually one of the most politically intelligent films Hollywood ever made.

Written by Rod Serling, the genius behind The Twilight Zone, the script is razor-sharp and full of irony. The role reversal with apes ruling and humans as the subspecies is a direct critique of the racial, social, and moral inequalities. And that ending — George Taylor (Charlton Heston) kneeling before the ruined Statue of Liberty — is still one of cinema’s most powerful moments. The message is simple but devastating: humanity destroyed itself. I remember watching that scene for the first time and just sitting there in silence. It’s one of those plot twists that completely reframes the story, turning the blame back on the audience. It’s what Martin Scorsese would call “absolute cinema.”

What Planet of the Apes proved is that sci-fi could tackle serious subjects without losing its audience. It balanced entertainment and critique with a kind of boldness that few films have ever matched — and remember, this was 1968. Decades later, the franchise was revived not just out of nostalgia but because its themes still hit hard today. From ideological wars to environmental collapse, it all still applies. The film shows that the future is only terrifying because it reflects our present.

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Defined the Future

While cinema was already transforming, literature was starting to catch up — thanks to Philip K. Dick, whose novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? went mostly unnoticed when it came out. It didn’t have the visual power of those two massive films, but its ideas were so strong that they ended up influencing nearly everything that came after. When I first read it, I finally understood why sci-fi fans talk about it with such reverence. Dick wasn’t trying to write about the future; he wanted to understand what happens to the human soul inside it. And for 1968, that was revolutionary.

The story takes place in a post-apocalyptic world, following Rick Deckard, a bounty hunter tasked with “retiring” androids that look indistinguishable from humans. But the more he does it, the less sure he becomes about what being alive even means. That constant questioning of empathy, consciousness, and authenticity is what makes the book so brilliant. Dick basically predicted every modern debate about technology: What’s the difference between a real emotion and a programmed one? What happens when machines start to feel, and we forget how?

It took years for the book to get the recognition it deserved, and only when Ridley Scott adapted it into Blade Runner in 1982 did its genius fully click. The filmmaker turned Dick’s existential dread into neon and rain but kept the philosophical soul intact. And it’s wild to think it all started back in the ’60s, with a novel few people even noticed. To me, it’s the bridge between classic and modern sci-fi — the point where the genre stopped being about technology and started being about consciousness. Without it, there would be no cyberpunk, and probably no real discussion about AI as we know it.

Looking back at 1968, I don’t just see a turning point — I see the birth of modern sci-fi. That’s when the genre stopped asking for permission and started dominating our collective imagination. Without 2001, Planet of the Apes, and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, audiences might never have learned to take sci-fi seriously. Alien wouldn’t have its existential terror, Terminator wouldn’t question fate and technology the same way, and The Matrix wouldn’t dive so deeply into the line between reality and illusion. These works built the foundation every other sci-fi story stands on, and honestly, no one’s ever fully topped their impact. They proved the genre didn’t have to choose between entertainment and depth; it could do both, and still leave you questioning what it really means to be human.

Fifty-seven years ago, cinema changed forever — and this isn’t just nostalgia, but returning to the moment sci-fi grew up. It was when the genre stopped pretending to predict the future and started confronting the truth about the present. Because, at the end of the day, the best sci-fi isn’t the one that distracts you for two hours, but the one that sticks in your mind and never leaves.

What do you think about these movies? Do you think they really changed everything in the world of sci-fi? Let us know in the comments!