Chris Suellentrop, a freelance contributor to The New York Times, wrote an opinion piece printed on Sunday (October 26, 2014) regarding the future of video games and the recent Gamergate debacle. The column is generally thoughtful and well written with one major exception. Suellentrop makes a comparison between video games and comics, and uses it to diminish the value of comics as art.

Videos by ComicBook.com

If this continues, the medium I love could go backward into its roots as a pastime for children. Instead of being a mainstream form of entertainment, it could end up being something like comic books, a medium that has never outgrown its reputation for power fantasies and is only very occasionally marked by transcendent work (‘Maus’, or the books of Chris Ware) that demands that the rest of the culture pay attention to it.

There’s no way around it. This statement is deeply, incredibly, blatantly ignorant of the subject matter it mentions and quickly dismisses. It treats the comic book medium like an inherently less valuable artform, represents an evolving reputation in the most diminutive form possible, and speaks as if only a few comics are worthy of any critical attention. The various problems found in this paragraph deserve to be unpacked.

Suellentrop stages the argument by acting as if the most valuable commodity in art is to be thought of as mainstream. If the column was based purely around the status of video games as a popular form of entertainment, this might be a fair consideration. But it is not. The focus of the piece is on the medium’s ability to be taken seriously as a form of art, one deserving of criticism and consideration. The only reason to connect those two ideas is to create a shortcut to artistic viability for the medium of video games, a relatively new art form that is massively popular. The concern that not being part of the mainstream invalidates the value or quality of art is patently silly. Looking back at the last century, for example, it’s possible to see blues transform from an outsider in popular music into a mainstream art form whose oldest artists are praised for their form and style. If Suellentrop is actually interested in video games’ advancement as an art form, then his focus in the above paragraph is clearly in the wrong place.

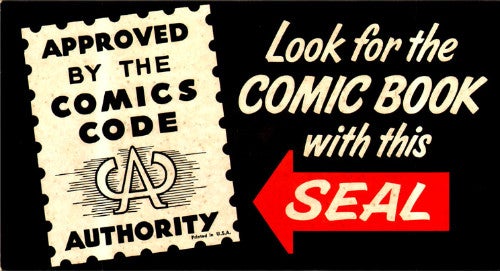

There’s certainly some truth to the assertion that comics are perceived as “power fantasies”, but it’s far from the whole picture. What may have been the status quo in 1954 when the Comics Code Authority was formed is no longer the widespread perception of comics. Comics are taught in classrooms across the United States. Comics creators are winning national and international literary awards. The medium is recognized for its limitless potential with the assistance of Hollywood. Although some people may still be unaware of the inherent value of comic books as an art form, that arguably no longer applies to most Americans. And this assertion also ignores the widespread popularity and acceptance of comics in countries outside of the United States, most notably Japan, France, and Belgium.

The single most troubling part is the conceit in Suellentrop’s opinion piece is that comics produce “only very occasionally… transcendent work”. Looking at my bookshelves alone, I am staggered by the problems in this statement. From immense conventions like San Diego Comic-Con to smaller affairs like the Small Press Expo (SPX), it’s easy to see in person the enormous diversity and quality of art being produced in the medium. And every week in comic book shops and bookstores across America it is possible to discover dozens of new comics for a wide variety of readers, expressing incredibly personal experiences, challenging cultural ideologies and precepts, and often doing both at the same time.

There is no value to be found in attempting to determine the comparative value of different forms of media. Yet it’s undeniable that the breadth and scope of comics produced in the past ten years alone far outmatches that of video games. The quality and diversity of art being produced in comics is something that the video game medium should aspire to, not disparage.

Suellentrop’s brief examples of transcendent work are certainly excellent, but are also the two most obvious examples available. It reads as if he has no foreknowledge of the medium and instead googled the phrase “good comics”. This reveals a minimal lack of research or concern, focused only shallow misperceptions rather than any actual understanding.

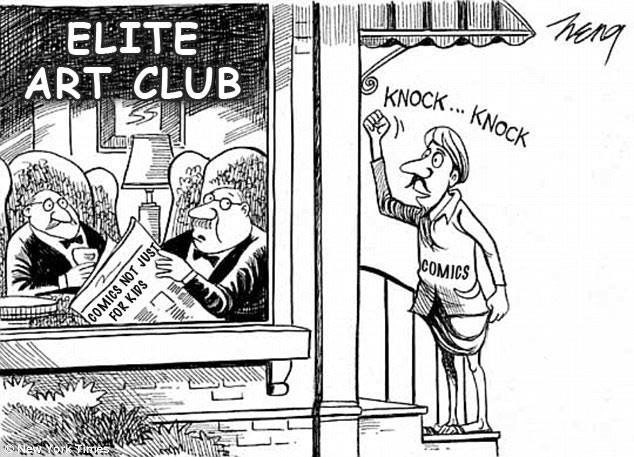

All of this relates to an idea that creators, critics, and readers of comics are all too used to hearing: comics are just for kids. It’s the most common objection made by those unfamiliar with the medium and, very often, the first objection expected by those who are. People on both sides of that divide have become used to comics being perceived as a children’s medium, no matter how silly that idea has become.

The statement “comics aren’t just for kids” hasn’t been relevant or necessary since the 1960’s.

The problem is not that comics need to overcome a reputation of being childish power fantasies. The problem is that this idea needs to stop being perpetuated by people who ought to know better. People like Suellentrop.

Ignorant statements like his are the basis for much misunderstanding in popular culture, and it’s an issue that can be resolved through discourse and research. The problem here is not what Suellentrop said, but that it was said by Suellentrop in The New York Times. A journalist for a well-respected newspaper made an unfounded comment that unfairly disparages an entire medium. If he had made these comments at a bar with friends, it wouldn’t be difficult for someone to point out the absurdity of his argument. Instead, it has been published by one of the best known periodicals in the world for all to read.

Comics have not been just for kids for a very long time, and this argument should have died more than forty years ago. There is no need to justify their value anymore. Academics, critics, and readers all understand that comics are capable of being and often are high art. From the best known and most renowned works like Art Spiegelman’s Maus to incredible independent comics like Lars Martinson’s Tonoharu or Erika Moen’s Oh Joy, Sex Toy, comics have established themselves as an art form with unlimited potential. Potential that is being recognized and harnessed everyday.

The continued existence of this misperception is not a reflection on the medium, but on the arbiters of cultural significance. Periodicals like The New York Times are willing to express the power and magnificence of comics in one column discussing Chris Ware’s Building Stories, then treat them like a lesser medium throughout the rest of the arts section. That sort of doublespeak only serves to continue an undeserved reputation. The problem isn’t comics, it’s the people writing about comics.

It’s time we all move past that notion. The medium has proven itself to be one of the greatest modern forms of artistic expression time and again. That is the reality of comics.

It’s time for that to be the conversation.