*This article contains some spoilers for the Netflix series Daredevil*

Videos by ComicBook.com

Daredevil premiered on Netflix last weekend to widespread acclaim from viewers and critics alike. The show currently boasts an impressive ratings of 97% on Rotten Tomatoes and 75 on MetaCritic; it’s movie predecessor in 2003 only scored 45% and 42. It’s not surprising, as there is a lot to enjoy in Daredevil. It boasts impressive performances, well-written characters and plot, purposeful and moody cinematography, and some of the best choreographed and shot action sequences of the past ten years. Honestly, there’s so much to like here (especially compared to Marvel Studio’s dismal previous pilot for Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.) that many people, myself included, may instinctively forgive any flaws. But that sort of mentality isn’t helpful for viewers or creators. Daredevil is certainly a great television show, that doesn’t even need the “superhero” qualifier. But it has its problems. One of these problems extends beyond Daredevil, but is put into an even clearer perspective because it’s a television show about a superhero. That problem is the use of torture.

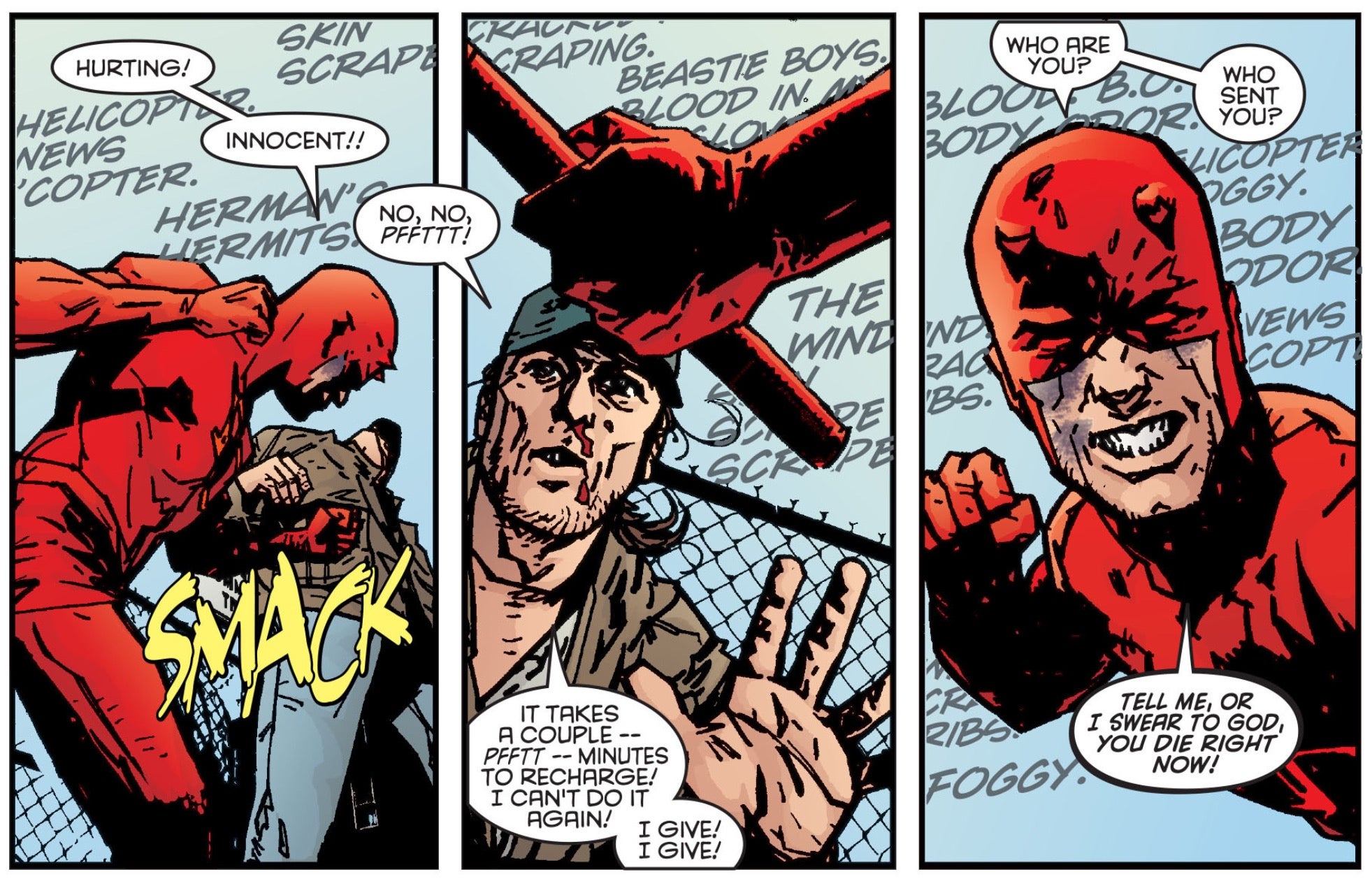

Daredevil uses physical force throughout the entire series in order to coerce information from criminals. He repeats the threat “If you lie, I hit you” multiple times, and he certainly follows through on it. Delivering punches in order to obtain answers certainly meets the definition of torture. Daredevil’s actions, especially within the first five episodes, goes significantly further. His beatings are extensively brutal, often crippling the hands and limbs of his victims.

The torture reaches its crescendo in episode two, “Cut Man”. Toward the end of the episode, Matt has a Russian hit man tied up on a rooftop. He beats him for information on the whereabouts of a missing child. After the man shows reluctance towards any answers, Daredevil’s accomplice Claire recommends that he stab the man in his trigeminal nerve. Daredevil takes her advice and inserts a knife above the man’s eyeball, placing him in excruciating pain. Stabbing the man in his trigeminal nerve risks blindness and permanent facial paralysis at best. But the action could have lobotomized or killed the man just as easily as it inflicted pain.

The man eventually provides the boy’s location when Daredevil hangs him off a rooftop, and is then thrown off when he taunts Daredevil. Although the man lands in a dumpster, he falls for at least several stories. A drop from such a great height also risks death, with or without a dumpster below to provide a cushion. The potentially permanent results from such a fall only worsen the act itself. Daredevil is torturing a captured man. That alone should be enough to send off alarm bells.

None of this is to say that the very idea of Daredevil torturing a criminal is beyond consideration. It has roots in some of the best source material available from writers and artists like Frank Miller and Brian Michael Bendis. The significant question to consider is context; to ask how Daredevil presents torture.

Raising that question creates a very troubling picture at the start of the series. In Daredevil, Torture is regularly applied with little consideration for the information’s significance. Daredevil’s beatings are used to not only help him rescue victims, but to obtain names and other information that are not time-sensitive and could be discovered through less violent means.

Neither Matt Murdock nor the show itself ever questions the morality of torture in these scenes. Daredevil never emotes signs of regret or questions the necessity of his own actions. The closest he comes is attending confession in scenes that never actually disclose what sins he is repentant for and how regretful he truly is. In the rooftop scene from “Cut Man”, Claire is troubled by his methods not because he uses torture (she actively assists his efforts), but because he claims to enjoy the act. In that same scene director Phil Abraham plays torture for a laugh (one of very few to be found in the episode) when Daredevil hits the man even after he gives the right information. The tortured man is far from deserving of sympathy, but the use of levity reveals a subtle approval of Daredevil’s actions.

In that same scene, context makes the situation simultaneously better and worse. The information that Daredevil seeks is both time-sensitive and life-saving. It is the classic “ticking time bomb” scenario presented in courtrooms in order to justify the use of torture, when no other options could potentially protect human lives in a timely manner. Whether or not you personally agree with the argument, it is one with some merit. However, when you consider the incredibly risky action of stabbing a man in his eye socket and throwing him from a potentially lethal height, Daredevil’s justification does not seem to align with the need to preserve life. He not only inflicts pain, but continually risks the life of his victim even after he has the information he needs. The hit man is later found in a coma at the hospital with no certainty of ever reawakening. A slight twist of fate and Daredevil would go from being a torturer to a murderer.

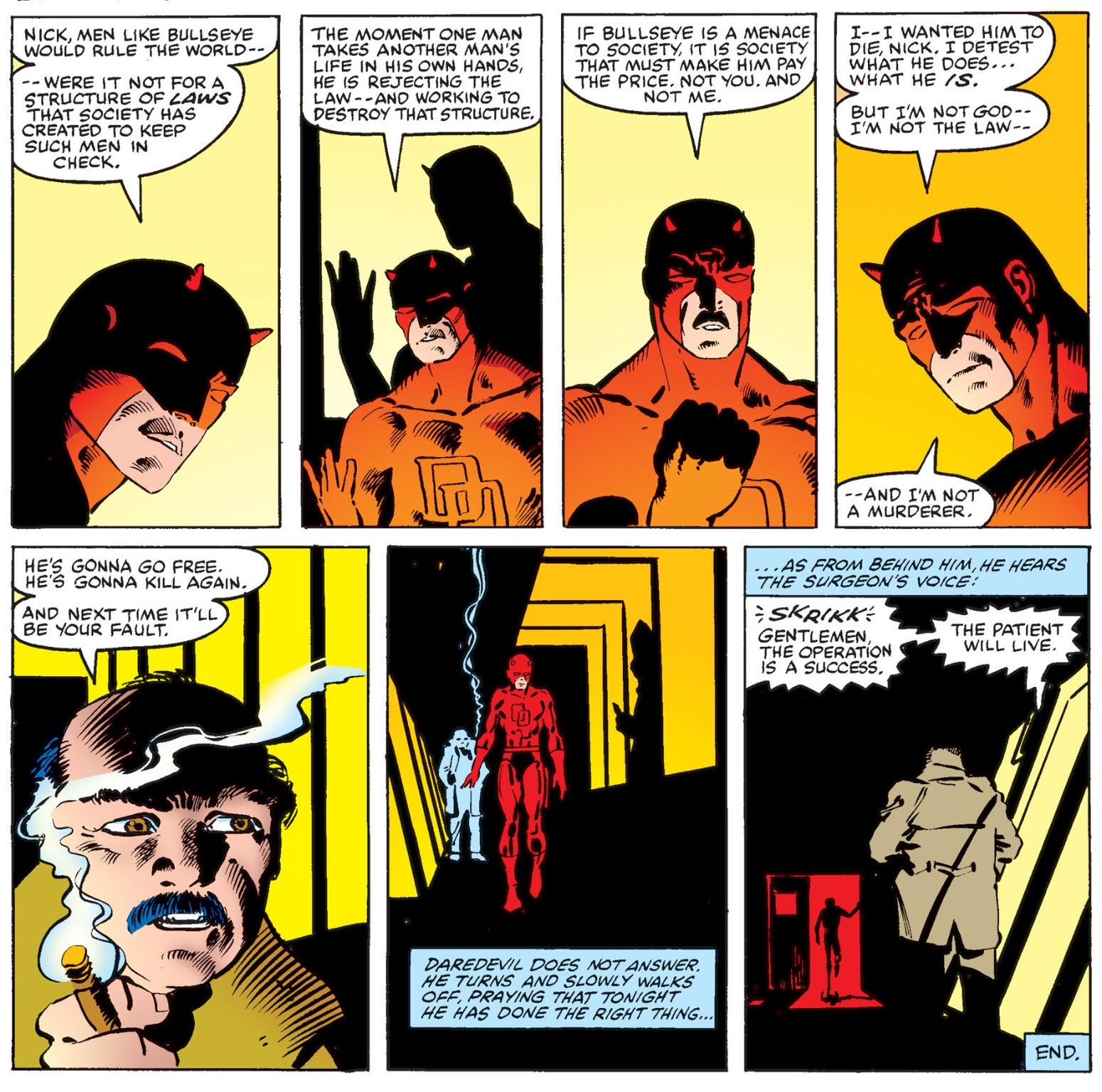

These scenes also risk undercutting one of the series’ most significant and best-crafted sub-plots. As a confrontation between Daredevil and Wilson Fisk builds, Daredevil is forced to question whether he is capable of murdering Wilson Fisk and– even if he can–whether he should. It’s a line that he refuses to cross, one that is outlined and praised in the episode “Stick.” However, that line looks arbitrary and inconsistent when placed alongside scenes from earlier episodes. Daredevil is presented as a man concerned with the sanctity of human life and the morality of his actions. Yet he also risks the lives of his opponents and only views their survival as a bonus. These are not the subtle contradictions of a complex character; they are simple contradictions that only work if the audience accepts torture as a morally justifiable act.

This is far from the first time that torture has been presented on television in this manner, and even further from being the worst. The most obvious example would be the network series 24 in which hero Jack Bauer regularly uses a wide-variety of torture to save the day. This series had the benefit of debuting only a couple of months after 9/11 in a political atmosphere, the where the American consciousness was very open to any action that ensured national security. But even almost fifteen years later, it doesn’t look like that acceptance was waned. In Arrow, another superhero television series, the protagonist not only tortures, but murders his enemies on a regular basis (a tendency that has waned in more recent seasons). The torture found here is difficult to imagine as heroic in a similarly popular series in a pre-9/11 landscape.

None of this is to say that torture is something that cannot be seen on television or that cannot be performed by protagonists. It is all a matter of how and why it is being presented. The issue with Daredevil is not as simple as “Daredevil tortures people”, it is a much more complex examination of how torture is presented and what ideas and morals that presentation reflects. Daredevil does not present the act of torture as a reprehensible or questionable action. Instead, the hero uses torture on a regular basis and is eventually applauded by his friends and the public. The torture in Daredevil is not troubling simply because it exists, but because it is unchallenged as the actions of a hero.

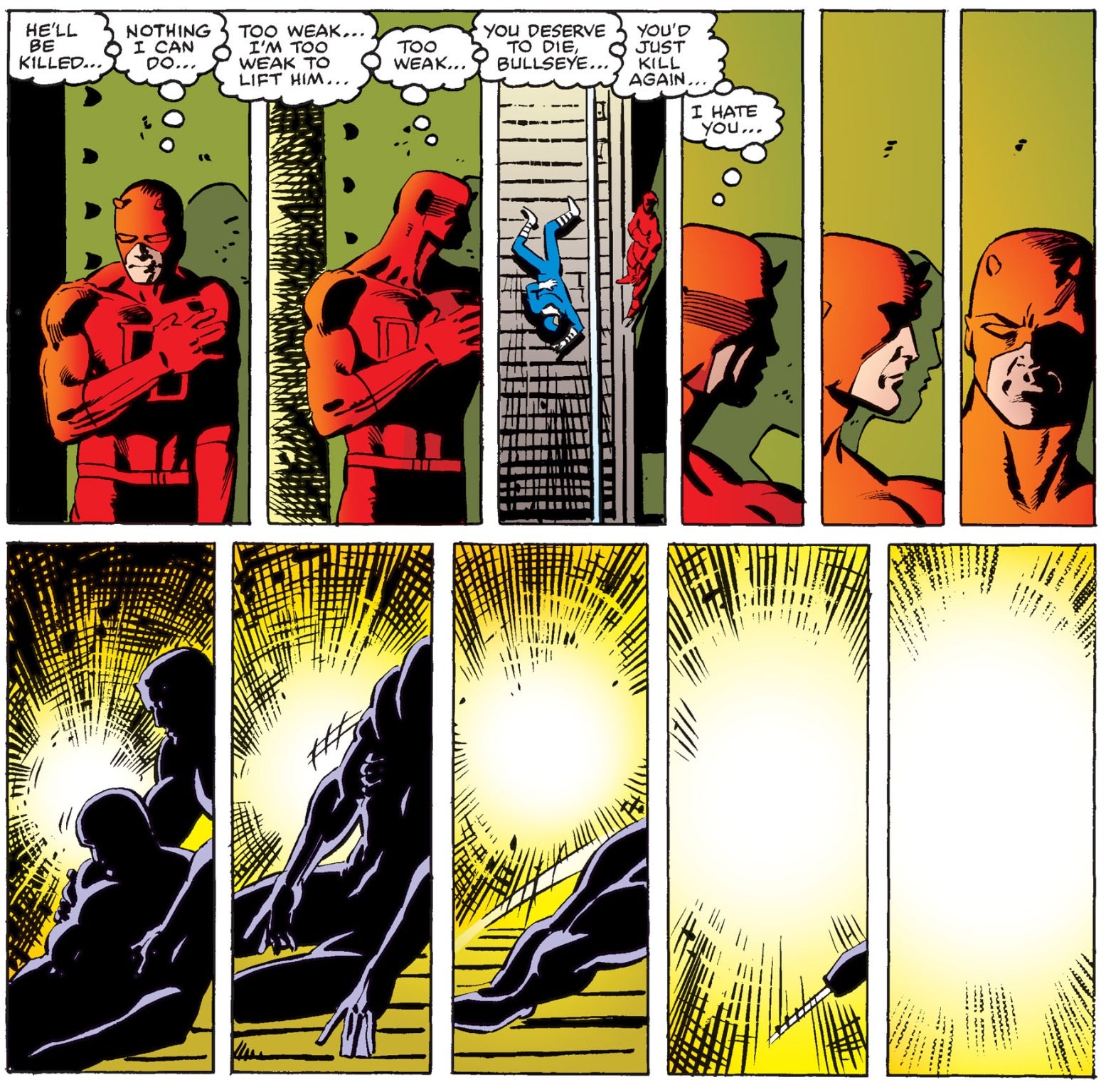

Torture and savagery have always existed as part of the character in comics, but it has never existed in such a morally simplistic zone. The moments when Daredevil has come the closest to darkness in the past, like his gut-wrenching scene in “Cut Man”, he has not been acting as a hero or been praised by the context of the scene. Perhaps the best analogs come from interactions with his nemesis Bullseye. In Daredevil #181, written and drawn by Frank Miller, Bullseye has killed Daredevil’s lover Elektra leading to a rooftop duel between the two men. At one point Bullseye falls and is caught by Daredevil. As Bullseye threatens to kill more people and swings a sai at Daredevil’s hand, Daredevil releases him and says, “You’ll kill no one — ever again!”

Although there are mitigating factors, it is clearly presented as Daredevil’s choice to let Bullseye fall to his potential death. The fall only paralyzes Bullseye, but the real consequences fall on Daredevil. In both this scene and the issue’s ending, nothing about this choice is portrayed as heroic or brave. Bullseye’s landing is cast in ugly hues and highlights the violence of the moment. Afterward, Daredevil is shown alone in the winter cold left to mourn Elektra while Bullseye sits in a hospital bed plotting an inevitable revenge. The context of the issue focuses on the pain and consequences of what has been done.

This issue is all the more powerful when taken in the full context of Miller’s run. In Daredevil #169 Daredevil saves Bullseye after he has been gone on a murdering spree due to a brain tumor. It is not an instant or easy decision though. He waits until the very last moment to pull Bullseye from the path of an oncoming train. The choice is a struggle, one that questions the basis of both Daredevil and the reader’s morality. Miller does not create a simple scenario in which right and wrong can be separated easily. Instead, he provides a complex struggle so that even when Daredevil risks the life of a psychopath and mass murderer 12 issues later, it is troubling. There is an epilogue in Daredevil #169 that allows Daredevil to present why he made his choice, but even that scene casts shadows of doubt.

That’s the sort of subtlety which best allow heroes, super and otherwise, to challenge us. It’s the kind of back-and-forth morality play that can be found later in Netflix’s Daredevil, but is also absent from the series’ beginning. Torture is not a fantasy or genre-element, it’s very real and something that has become a significant part of the American national discourse in the past 15 years. To accept it as a heroic act so easily is bothersome because of what that it says about its viewers. It proposes a worldview in which torture is acceptable under a wide variety of circumstances, and can even be seen as heroic or humorous.

If we are all ready to accept that proposal, then maybe this isn’t a flaw with Daredevil. Maybe it’s a flaw with us.