Videos by ComicBook.com

This comic breaks down into two parts, the Grant Morrison penned “The Priest & The Dragon: October Incident: 1966” and “The Miracleman Family: Seriously Miraculous” which is written by Peter Milligan with art from the inimitable Mike and Laura Allred. Both of these pieces are entertaining and engaging in their own rights, and I will be addressing each in turn. Intriguingly, the two are almost polar opposites in terms of tone with the subject matter, art style, and coloring setting each apart as being very different looks at the Miracleman mythos. This is an interesting choice and helps point to the variety of stories that can be told within the world of Miracleman.

SPOILERS“October Incident: 1966” is a story that was originally written by Grant Morrison in the early 1980s for publication in Warrior, the British magazine in which Alan “The Original Writer” Moore’s deconstructionist take on the Miracleman character first appeared. The story goes that Morrison wrote the piece but Moore told him in no uncertain terms to “back off” and thus the story was unceremoniously killed. Whether or not this is an accurate representation of what went occurred 20-plus years ago, this is the first time that the comic-reading public is being treated to this entry into the Miracleman saga. Reading it in the context of what was supposed to have been part of the early Miracleman stories and presented in the typically six-paged format of Warrior, this feels very much a part of Moore’s work with the character and his world.

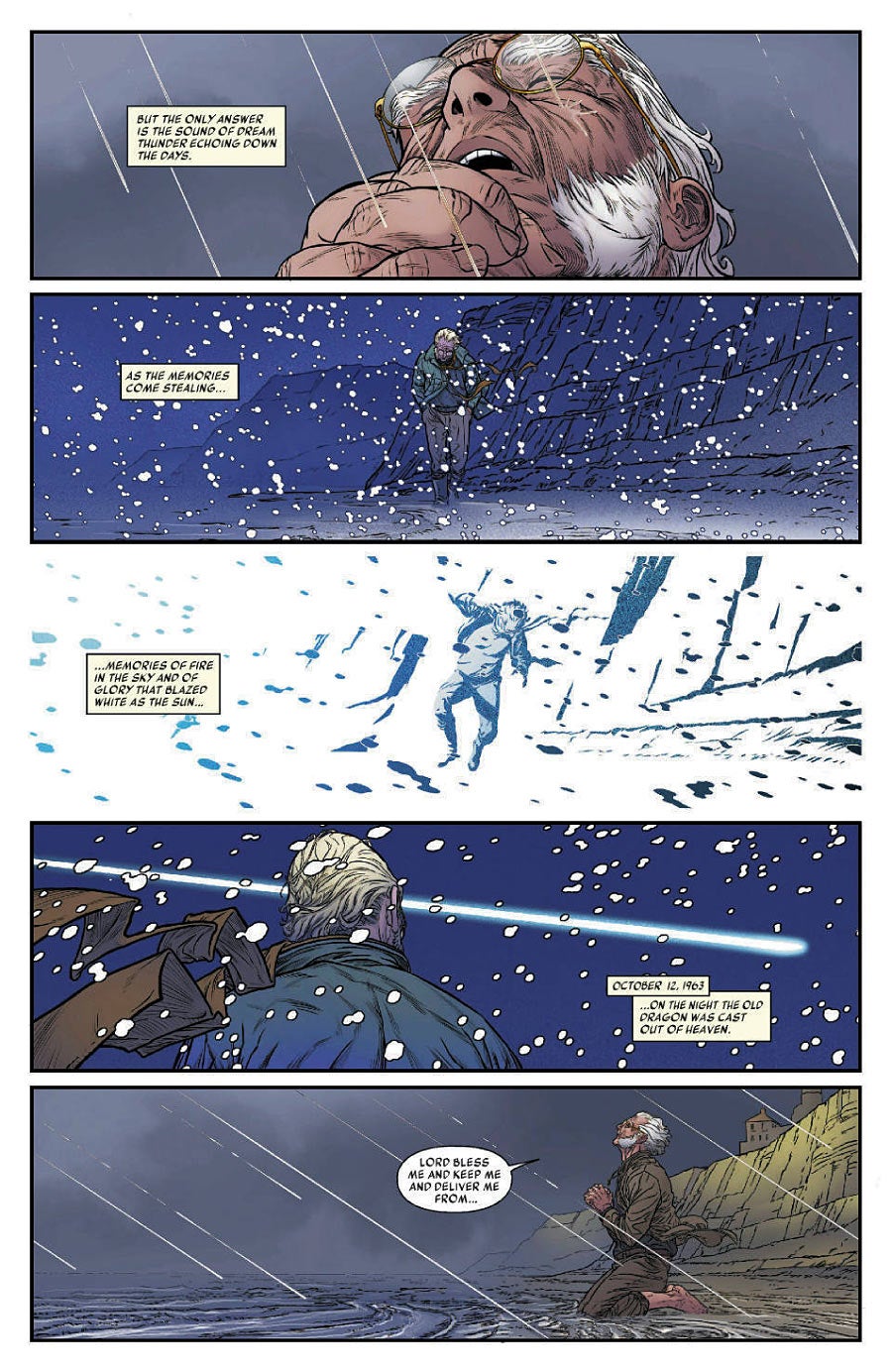

As presented in All-New Miracleman Annual this story has been allowed to stretch to eleven pages with art by Marvel’s Chief Creative Officer Joe Quesada. This elongation is to the piece’s benefit, allowing it to breathe and for Quesada’s pencils to revel in every moment of the tale. The story itself is a simple piece illustrating an early incident in Johnny “Kid Miracleman” Bates’ transformation from hero to villain. The story opens on a priest walking the beach somewhere in England. He remembers back to three years earlier when he saw something plummet out of the sky and land nearby. This something was, as it turns out, Bates who’d been blown out of the sky by the British military intelligence agency Spookshow in their attempt to destroy the Miracleman Family. Subsequently, Bates appears and engages the old curate in conversation before ultimately killing him in spectacular fashion.

Starting with Morrison’s writing, I am thoroughly impressed with the deftness evinced by this early work of his. This story and the writing style meshes almost seamlessly with Moore’s work on this series at the time. In fact, Morrison’s relatively simply-stated narration is in my opinion head and shoulders above some of Moore’s byzantine narrative captions of the same period. Morrison also does a great job of working within Moore’s established imagery, playing on the idea of Bates as a metaphorical dragon and thing of evil. Though a simple story, the image of a young man and self-proclaimed reader of Nietzsche destroying an old priest while referring to him as a witch doctor is rife with meaning and symbolism. Helpfully, the back matter lays out some of this symbolism in no uncertain terms, pointing out Bates as an embodiment of nihilism rejecting the moral values imposed by religion to be eventually overcome by the potential Nietzschean Ubermensch of Miracleman. Giving Bates a Beatles-inspired look and setting this story in 1966 also (as again pointed out in the back matter) echoes the well-remembered John Lennon quote wherein he describes the Beatles as being “more popular than Jesus.” This confluence of meaning, symbolism, and cultural reference is a hallmark of Morrison’s work and it’s exciting to see it in play this early in his writing.

Turning to the artwork, Joe Quesada (pencils/inks) and Richard Isanove (color) have perfectly complemented Morrison’s writing. This may be the first time that I’ve actually read a comic book with art from Quesada and I have to say that I love his style. Everything is nicely detailed, characters’ expressions are subtle but well-conveyed, the mood and tone come across nicely, and the variation in panel size from the equivalent of a twelve-panel grid to full page splashes are well-utilized. I also have to applaud his Eisner-esque incorporation of the story’s title into the rock formations on the side of a cliff, though the smaller names of the creative team become nearly indecipherable. Really, I can think of no complaint with regard to Quesada’s visual interpretation of Morrison’s script and the colors from Richard Isanove are beautifully dark and muted with the obvious exceptions of the lightning bursts.

I also have to applaud Quesada’s addition to Morrison’s script of the Hamlet-esque holding of the priest’s charred skull by Bates, echoing the graveyard scene with the skull of the jester Yorick. In Hamlet, Yorick is identified as the jester that entertained the Danish prince in his youth. Here a parallel can be drawn with religion being the system of meaning that “entertained” Bates as a child which he has now outgrown and rejected on his path to a kind of nihilistic godhood. This seamless addition only reinforces the ideas at play and personally I always enjoy a good nod to Shakespeare.

Warrior“Seriously Miraculous” is a bit of fluff. Still, it is a fun bit of fluff with art from Mike and Laura Allred so it’s more than welcome in this annual as far as I’m concerned. The story is relatively straightforward and takes place in the pre-Moore Captain Marvel/Shazam-knock-off days of Miracleman, though one could also say that it takes place in the Miracleman Family’s Gargunza-induced dreams. We find the Miracleman Family (Miracleman, Young Miracleman, and Kid Miracleman) fighting Gargunza and the Boromanians, then some crazed dolphins, and finally Young Nastyman and Young Gargunza in a series of vignettes. Throughout this series of dust-ups and donnybrooks, Miracleman is wondering why no matter how much destruction is wreaked and how hard he punches anyone, no one is ever seriously hurt. Young Miracleman then asks how serious he would want the world to be. Miracleman thinks for a second and rejects his earlier musings before declaring, “Let’s go get the bad guys.” The comic then close-ups on Miracleman’s face revealing the Ben-Day dots that give him color and thus the artificiality of his world.

I call this story by Peter Milligan a bit of fluff and I do so primarily because the main themes/ideas of this story have been done before in the main Miracleman narrative. The idea of Miracleman going through his idyllic Miracleman Family days and realizing that they don’t have an internal consistency was the entire point of (by Marvel’s issue numbering) Miracleman issue 6’s revelations. That issue showed the Miracleman family going through an adventure induced by Gargunza’s dream machines wherein the subconscious symbolism and inconsistencies were broadcasting to Miracleman that his world was not the reality it seemed. Gargunza, operating the dream-inducer in the real world was fearful that Miracleman and the rest of the family might actually shake themselves out of their dreams after realizing their unreality. Milligan’s story here seems to be more-or-less exploring the same situation albeit in a less serious manner. Perhaps I’m reading too much into this and Milligan is attempting less a rehash of the Miracleman Family’s questioning their reality and is simply having a laugh at how utterly serious and dark Moore’s take on the character could be. Still, it’s hard not to examine this piece in detail given the themes explored in Moore’s work and the analysis that it warrants.

Batman ’66 BatmanTurning to the art, what can I say about the Allreds that hasn’t already been said before? Their style is unmistakable and always welcome. If you’ve seen their work before, then you know exactly how you feel about it. Personally, I love it with its clean lines and bright colors. Mike and Laura Allred’s work is a perfect complement to this sort of story, and the only negative I can think to bring up is that Young Gargunza is pretty visually indistinct from regular Gargunza. This might be an artifact from the original source material but regardless it would have been nice to set him apart somehow even if only through a propeller beanie or some similarly goofy accoutrement.

Taken as a whole, this is a comic that is well worth your time and attention. The back matter is even an improvement over that of the main Miracleman series in that there is actual context provided for the work through some written commentary. This is exactly the sort of thing I’ve been asking for in my reviews of the main Miracleman series to add value to the pages upon pages of reproduced original art. As any comic book you might pick up off the stands, this is an interesting, enjoyable, and fun read. As an entry into the Miracleman mythos, this is indispensable. I suggest you pick up a copy and read it for yourself at your earliest convenience. Admittedly, the $4.99 price tag is a bit steep but in this particular instance I still recommend picking up this book.