Collecting Comic art is becoming more than a hobby for casual enthusiasts, growing into a large, and lucrative, business. A little note about myself, I’ve collected comic art since 2007. And while I’m not nearly as experienced as some of my peers, I’ve come to learn a lot about the business and the etiquette that goes along with it. I’ll discuss said business, and more, in “The Folio,” a new column for ComicBoook.com. For the debut installment, I wanted to address a topic that’s receiving more and more conversation: traditional vs digital art.

Videos by ComicBook.com

There’s a change coming to the comic art world. Once, it was all traditionally crafted with pencils, pens, brushes, nibs, ink, and the usual tools of the trade you might have found in How To Draw Comics the Marvel Way. But now, there’s a generation that has transitioned into digital art. Drawing on Wacoms and Cintiqs is becoming more and more instinctive for this generation. Even veterans like Kevin Maguire have made the jump to digital for published works, and you have artists like Robbi Rodriguez who, due to an ongoing medical condition, has gone full digital and can no longer do physical, traditional commissions.

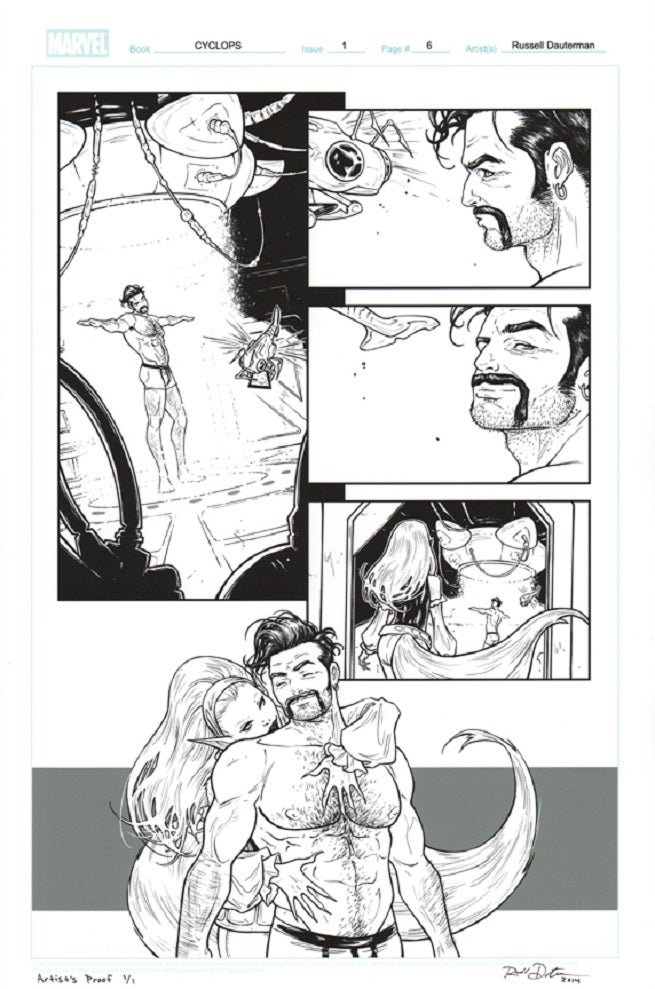

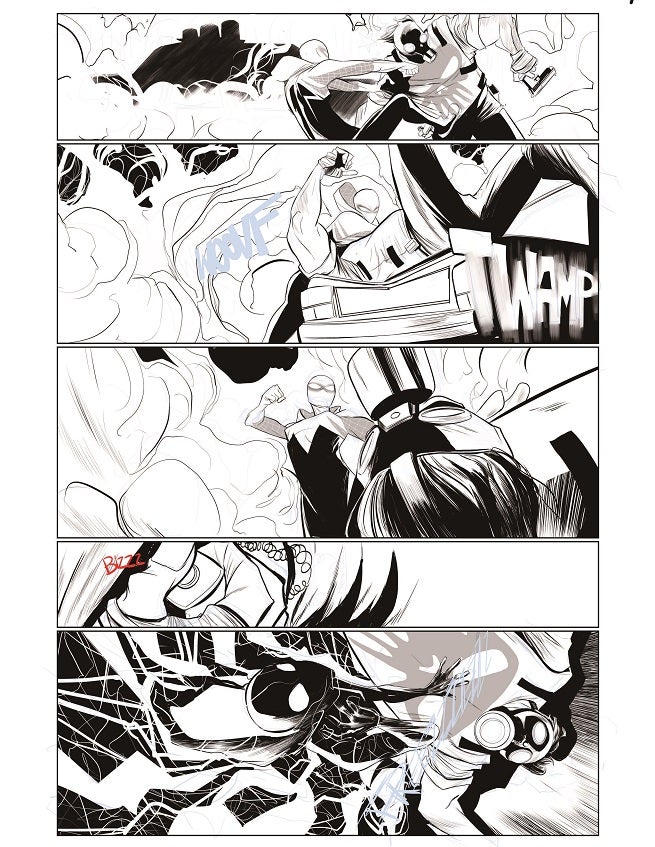

So what happen when an artist can’t sell those pages or rely on commissions as additional income? Does the money stop on the digital pad? Not necessarily. There are things called “proofs” that some artists sell. Take Thor and Cyclops artist Russell Dauterman for example. He opened up a store with artist’s proofs for his comic pages. What exactly is a proof? Well, Dauterman actually has a solid definition on his site: “artist’s proofs are the closest he gets to original art in the traditional sense these days. Once he finishes drawing a comic book page, he makes a high-quality, inkjet print (the proof) of the page. Each proof is 11×17 on Strathmore Bristol 500 series board and is signed by Russell. Only one proof is sold per page.” Pretty cut and dry, right? For page rates, you get a print of the page and some sort of certification that guarantees it’s 1/1.

Now this isn’t a new practice or anything. Photographers have been selling prints of their work and colorist Dave McCaig had a similar method a few years ago.”When I had Color Master Prints running, it worked great. I was selling Marvel-approved prints for relatively high page prices,” McCaig says.

While he did already have an embossing stamp with the company logo for the pieces, he further explained that he had planned to unroll a system that allowed patrons to verify that the “page they purchased was indeed the only copy in existence–just like a penciled page. “My system was double-blind. You could track pages on a website with unique tracking number, so if you bought previously-owned pages, you could make sure it wasn’t just a copy or something,” McCaig said. “I thought of figuring out a way to contact previous buyers via blind-email as well, like some e-retailers of used goods let you do.”

This puts a whole new category on the art collecting market: digital proofs. Now think about this for a minute: What if digital artists like Fiona Staples starting selling proofs from Saga. Would you pony up the money for that? Since you’d technically have the only physical copy, it opens a debate on what a fair price would be. There’s still plenty of skill involved in creating art on the page, but the evolution of the medium might change some people’s ideas on buying them. Some customers buy simply fans, but others do use it as investing in stock in the artist as well. Should something like this affect the artists’ stock or prices if their pieces are only available in digital form? That has yet to be determined.

Not everybody thinks this is a good business plan. Spider-Gwen and Frankie Get Your Gun artist Robbi Rodriguez has mentioned he would sell some proofs, but for a fraction of that price of about “$50-100”. Some would say since he’s no longer doing originals, that might be more of a deal, but he has some thoughts on to selling proofs instead of your originals. “Honestly, I think it’s shady,” Rodriguez says. “Doing digital and not having originals is the down side to the tech, but this is also coming from someone who could care less about my own original art and toss most of them in the trash after they are scanned.”

He continues with that if it works for certain artists, that’s great, but he’s wary of the system. “If you can make a buck on it, great, I guess. Though most cartoonists are very much like carnies,” he says. “What’s stopping them from printing a hundred copies of the same page, then tell the buyer at a show that they have the only one? The same amount of work, if not more, is involved. But it’s not the same as having real art to sell. Convenience comes at a price.”

Artists creating digital commissions is also nothing new, but they usually keep it at the $10-25 range, if that. Is there a specific line drawn between digital commissions, and proofs of published pages that shouldn’t be crossed? Do you think it’s still worth it? Personally, I don’t have a lot of digital pieces in my collection. In any case, I don’t purchase prints either, unless I know it’s something that I could never afford the original version of. I prefer traditional art, but understand that change is in the wind, and the up-and-coming generation is learning a whole new set of skills that are being used to create an entirely new world of comics.

Obviously, traditional art isn’t going away anytime soon. And digital isn’t either. There is room for both schools of thought to work side-by-side in the industry, but are the veteran collectors accustomed to only buying traditional art going to dip their toes in digital offerings? That has yet to truly be seen.