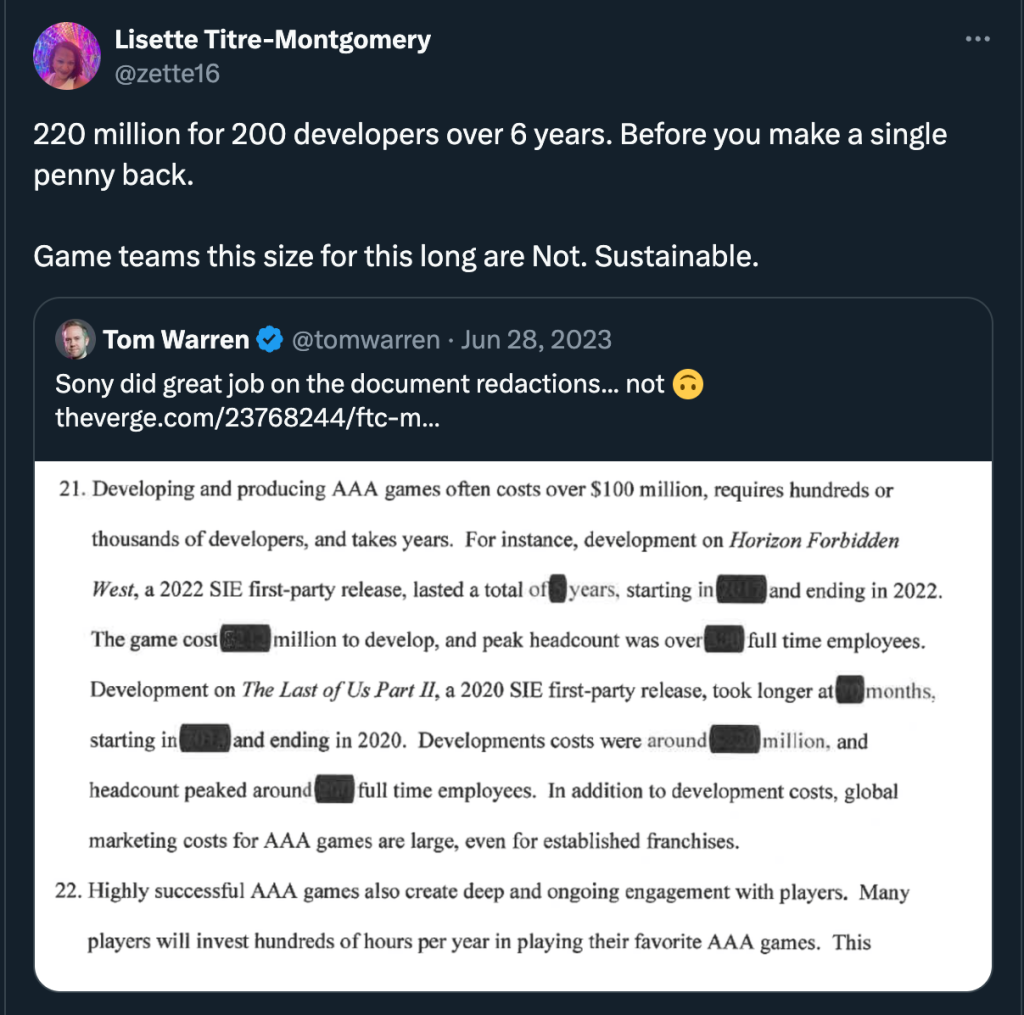

Video games — particularly AAA video games — have become too expensive to make. The intel from every fly on the wall in every investor’s room is there is an increasing level of caution about spending hundreds of millions just to release a single video game. And you can’t blame them. Many AAA game budgets mean that you can print hundreds of millions in revenue, and not even turn a profit. If you are an investor, quite frankly, there are many easier ways to make a buck. AAA games have always been expensive to make though, but when did we go from expensive, to too expensive? A decade ago, AAA games were still expensive to make, but fears of “sustainability” didn’t keep every CEO up at night. Consumer expectations and demands no doubt play a role in this, but more and more games are also revealing obvious signs of resource mismanagement, evident by development teams and budgets spiraling out of control with sometimes nothing substantial to show for it.

Videos by ComicBook.com

Making the matter worse, it is individual developers who pay the ultimate cost for all this. There has been an unprecedented number of layoffs in the industry between this year and last year, and those who pay the price with their job have nothing to do with the horror stories of mismanagement, the rapid over hiring during the pandemic business boon, and c-suite executives aggressively and recklessly chasing growth at every opportunity.

Starfield and Bethesda Game Studios

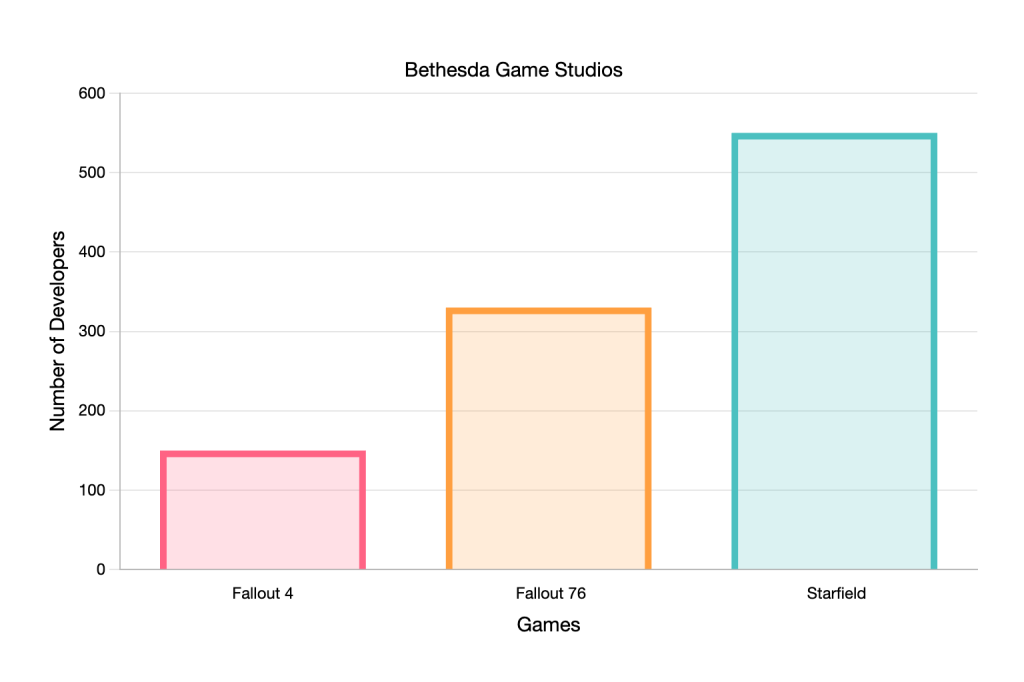

The latest illustration of this are some headcount numbers revealed by a former Bethesda Game Studios Design Director. According to these newly-provided numbers, 2015’s Fallout 4 was made by a team of 150 developers. Meanwhile, 2018’s Fallout 76 was apparently made by a team of 330 developers. This doubling in three years is alarming enough, but then there was another big jump. According to the same source, Starfield was made by a team of 550 developers. The obvious trend here is Bethesda Game Studios has been steadily, and somewhat precariously, growing in size with each game it ships.

To put the enlargement into perspective that is a 266% increase in size from Fallout 4 to Starfield. Suffice to say, Starfield is 4x the size as Fallout 4, right? Or at least 4x the ambition? If neither of these things then surely it was made substantially quicker….. right? Nope, none of these are true. In fact, none even come close to ringing true. Fallout 4 was made quicker, it boasts higher Metacritic scores, and according to How Long to Beat it takes longer to beat and/or 100% complete. So, where the heck did that 4x in resources go? It’s not clear. The final product is a great spacefaring RPG, but it nowhere near accounts for the exaggerate expansion of resources.

Let’s do some quick math to illustrate how much this headcount bloat can cost. According to Glassdoor the median salary at Bethesda Game Studios is $87,000. How precisely accurate this figure is, we can’t know for sure, but it lines up with Glassdoor’s more comprehensive average for the entire industry in the United States, which is $85,000 per year. On Starfield, there were 400 more employees to pay compared to Fallout 4. That means, at one point Bethesda was dropping an extra $34,800,000 a year. As you will know though, video games take years to make, at minimum. In the case of Starfield, it is unclear when exactly full production started, but we know by 2018 it was in production for some time and in a playable state. Starfield didn’t release until 2023, so you can see where that $34 million starts to rapidly grow out of control and devour your profit margins.

Marvel’s Spider-Man 2 Budget

None of this is to pick on Starfield or Bethesda Game Studios — a good game from a great, storied studio — as this problem is not unique to either. Let’s look at Marvel’s Spider-Man 2. The PS5 game from Insomniac Games shipped five years after its predecessor, yet somehow it cost 3x as much to make. Normally, or at least historically, sequels are cheaper to make because the foundation has been laid and the gestation period in pre-production is often much shorter. Meanwhile, both games are roughly 17 hours long to mainline, and the first game is actually packed with more content based on the fact it takes seven hours longer to 100%. So, the games have roughly the same amount of content, had similar development times, and the final products look fairly similar despite being an entire generation of consoles apart. So, how did the sequel end up costing 3x as much? Well, Insomniac Games itself was also curious about this.

A leaked internal presentation out of Insomniac Games literally stated, “…is 3x the investment in [Spider-Man 2] evident to anyone who plays the game?” If you increase investment 3x and have to ask if the investment is evident to anyone who played the game, that’s not a good sign, and it also obviously begs the question: to what end was the budget increased by 3x? It shouldn’t be understated how much of an increase this is either. A 3x budget increase is massive when you’re dealing with hundreds of millions. This isn’t to say the extra resources were flushed down the toilet, but the presentation asks a pertinent question: what end did any of it serve if it’s not particularly reflective in the final product? And if it’s not blatantly obvious in the final product then why is it necessary to the product?

If you intently watch the video below, you will see the technical upgrade of the second game. Do the games look drastically different? No. But upgrades to things like draw distance, NPC density, are all on display in the second game. And of course, the game also looks and runs better, thanks to the power of the PS5. There’s no denying any of this, but do you see the 3x increase in resources? You don’t, and this is where the changes are most obvious, because you are not going to notice it as much in the writing, narrative, music, or other parts of the game.

Raising Game Prices Is Not the Answer

Ballooning budgets and headcount is a problem that is weighing down the entire AAA industry. And unfortunately, it has recently led to significant industry-wide layoffs. As the industry wrestles with the problems and explores solutions, game prices keep coming up. To this end, game prices may look higher than ever, but the hobby actually used to be more expensive. Aka inflation is a heck of a deceiver. A $70 N64 game in 1998 is $134.13 in today’s money. This is just one of many examples because it’s true, game prices haven’t kept stride with inflation, partially because the market has expanded, and with expansion comes more casual consumption. And trying to convince a large, mainstream audience to fork over $134 for a game is never going to happen. Further, this is a band-aid fix for a modern problem. It’s treating a symptom, and perpetually passing the burden onto the consumer is not a foundation you can build sustainability on, it’s simply a fast track to shrink your market. Back in 2020, former PlayStation boss Shawn Layden suggested this very thing though.

“It’s been $59.99 since I started in this business, but the cost of games have gone up ten times,” said Layden at the time. “If you don’t have elasticity on the price-point, but you have huge volatility on the cost line, the model becomes more difficult. I think this generation is going to see those two imperatives collide.”

It didn’t take long for this last part from Layden to rear its ugly head. A year after Layden said this though, game prices did increase. Many AAA games, specifically, jumped from $59.99 to $69.99. They could increase again, like some want, and it is not going to dramatically change the situation. Fewer people will buy the game, and even more will wait for a sale, especially in a subscription service-influenced market where things like Xbox Game Pass and PS Plus are conditioning consumers to not buy games. It is also not going to change the situation because the problem is not on the returns.

Games are generating more revenue than they ever have before because of the expanding video game market. The problem is out-of-control development costs means the net income is a fraction of this revenue. Circle back to Marvel’s Spider-Man 2 as an example. Because Marvel’s Spider-Man 2 went from $100 million to make to $300 million to make, it needs to sell seven million copies — at full price — just to break even. This was never going to be a problem for the game, but you don’t spend hundreds of millions to only make a couple hundred million. That is a very risky investment with the upside not as appealing as the downside is terrifying. And again, these aren’t isolated examples. They are the rule, not the exception right now in the AAA space.

Raising game prices will help increase your margins on the back end, but it doesn’t address the actual problem, which is that you are spending too much to make your games. The last 10 years suggest it is also an exponential problem, not a flat increase that can be accounted for. In other words, not only is this problem not going anywhere, it is actually snowballing into a larger and larger issue over time.

Meanwhile, we’ve already seen experimentation on game prices. Some developers and publishers have essentially already increased prices through various special editions of the game that lure consumers into paying sometimes much more than full price with the bait of things like early access or exclusive content. And it has obviously not moved the needle, because it doesn’t address the problem that got you here in the first place. The problem is not the price of games, it is the cost of development. And there’s no denying ballooning teams in the weeds of technology and refinement that don’t measurably service the end product — like we see in Starfield, Marvel’s Spider-Man 2, and many other games — is a huge contributor to why development costs are out of control.

Game Length and the Pursuit of State-of-the-Art

The aforementioned Layden has not only suggested game prices need to increase, but game length and scope needs to be reduced as well. Obviously, the shorter the game is, the cheaper it is going to be to make, broadly speaking of course. And there is certainly some truth to what the former PlayStation executive is saying. Most Assassin’s Creed fans would agree Assassin’s Creed 2 is the best and most important installment in the series. It achieves this at 20 to 40 hours. A more recent entry, Assassin’s Creed Valhalla, is about 60 to 150 hours long. All of these figures are once again according to How Long to Beat. We don’t know the budgets of the two, but it is safe to assume AC Valhalla cost substantially more. And to what end? On the other side was a good product, but still an inferior product in context. So Layden is right, you can start tackling game development costs by reducing the content ambition of said games, which in turn means you should be able to keep teams leaner. There are examples that bolster Layden’s claim, but there are also examples that erode away at it.

Take the previously mentioned Starfield and Marvel’s Spider-Man 2. They are a similar length to their predecessors, but yet boast either substantially larger budgets and/or substantially larger development teams. And that’s because game length, like game prices, is not the problem for the skyrocket in development costs. Yes, some games and series, on average, are bigger and longer than they used to be, and in turn are costing more to make. Reeling in game length, in some cases, is no doubt part of the conversation, but it is also overstated. When comparing many others releases to their counterparts sometimes from a decade ago or more, the gap in game length narrows or doesn’t even exist in the first place. Ultimately, the relationship between game development costs speedrunning to unsustainable and game length is a tenuous one. And you don’t need to look any further than one of the biggest and most relevant releases of 2024 to illustrate this: Palworld.

Pocketpair made Palworld, a game that offers about 35 to 80 hours of content on a budget of $6.75 million. That’s right, it has a budget that is 2.25% of Marvel’s Spider-Man 2, yet manages to offer more content. Obviously, what Marvel’s Spider-Man 2 is doing per pixel is more impressive, but does the market care? In just two weeks Palworld sold two million more copies — just on PC — than Marvel’s Spider-Man 2 did in four months. This doesn’t even factor in its sales on Xbox. Of course, there are variables that work in the favor of Palworld, like its cheaper price point. There are also variables that work against it though, like the fact it is free with Xbox/PC Game Pass. The point is a circle back to that leaked Insomniac Games presentation; to what end were all those extra resources poured into Marvel’s Spider-Man 2 for and was the use of these resources a fundamental misunderstanding of market demand and expectation? There is certainly an argument to make that it was.

Developers may want to motion capture everything that walks, send their research team around the world, animate a character’s face until it resembles real life — in pursuit of making the best product — but the demands of the market simply doesn’t warrant it. Further, in an age of technological refinement rather than technological evolution in the gaming space, chasing state-of-the-art provides diminishing returns. So many extra resources were poured into Marvel’s Spider-Man 2 compared to the first game, yet the market didn’t seem to care, and possibly couldn’t even tell. There is no doubt demand for state-of-the-art games that push the envelope, and there always will be. Generally speaking though, there doesn’t seem to be enough cost-benefit analysis being run at some of these studios.

The Industry Is at a Crossroads

The problem has never been, and still isn’t, that AAA games are INHERENTLY too expensive to make or that game prices are not sustainable and need to be increased. We know the former is not true because this wasn’t always a problem, and we know the latter is not true because there are games printing more money than even spend-happy executives know what to do with, and some of them don’t even charge you anything to play them. There is plenty of money to make even at the current pricing model, and there historically — and currently — are many teams doing as much to various levels of success without breaking the bank every time they ship a game.

Right now, the math just doesn’t add up for many AAA studios. AAA game development is broken, like Layden suggested. It is not broken because consumer demands are running amuck nor is it the responsibility of the consumer to pay more to offer some level of momentary stability. Rather, there needs to be an examination of why so many development studios have grown so big and over-specialized to ship the type of games they used to do at a fraction of the size and cost not even a decade ago. Have many of these studios grown too big? Are teams getting lost in the weeds of expensive cutting-edge technology and refinement that is not evident to the player, and thus not going to be appreciated, and more importantly, rewarded? These are questions that need to be addressed before the burden is passed onto consumers to expect shorter, more expensive games.

Further, there needs to be an adjustment in order to create a more sustainable industry, for the sake of those who make games and the final products themselves. Whether it is Xbox/Bethesda, PlayStation, Take-Two Interactive, Epic Games, or just about any other player in the AAA space, all have felt the the costs of the current model. Even if you don’t care about the human element here, people losing their jobs and having their lives uprooted, and all you care about are the products they make, you should care about this vicious cycle. Creating a game in an environment tense with worries of layoffs is not the type of environment that will produce the best final product.

Right now, the industry is at a crossroads. It can continue down the current path where games are getting more and more expensive to make, more expensive for consumers to enjoy, and more difficult to make money on. There is another path though; where teams are agile and headcount is distributed across more projects; where the fetishization of technology and pushing the envelope for increasingly diminishing returns is reeled in; and where investors can chase the fat margins they are after without making the consumer pay substantially more while getting nothing different in return.