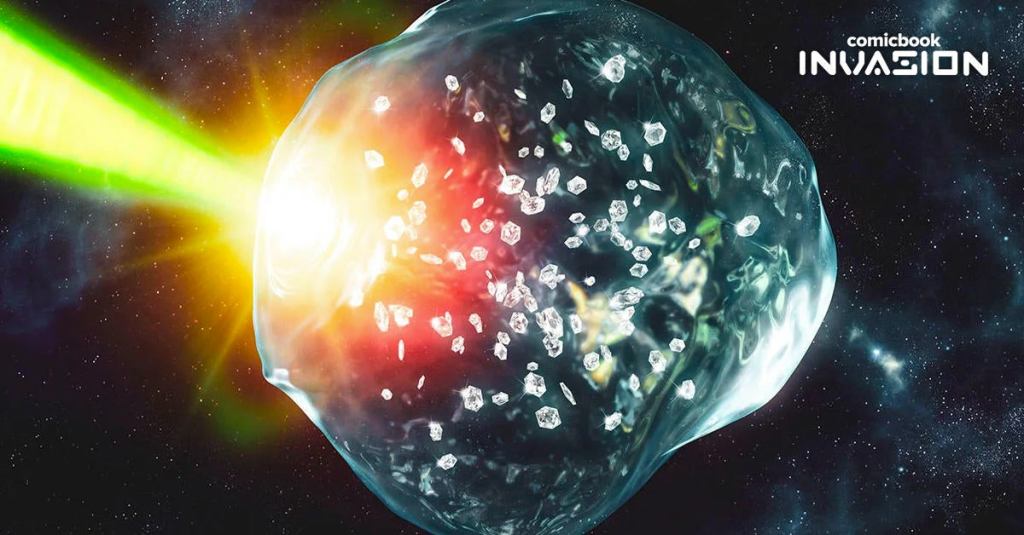

As it turns out, planets with atmospheres that produce raining diamonds might be much more common than previously thought. Previous studies suggest Neptune and Uranus have the capabilities of forming diamond rain due to the pressures in their respective atmospheres. Now, researchers from the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory have published a study suggesting the mere presence of oxygen makes the formation of diamonds much more likely.

Videos by ComicBook.com

In short, that means many more planets have the potential capability of producing raining diamonds.

“The earlier paper was the first time that we directly saw diamond formation from any mixtures,” Siegfried Glenzer, director of the High Energy Density Division at SLAC, said in a press release “Since then, there have been quite a lot of experiments with different pure materials. But inside planets, it’s much more complicated; there are a lot more chemicals in the mix. And so, what we wanted to figure out here was what sort of effect these additional chemicals have.”

Using a high-powered optical laser, researchers were able to create shock waves. They then analyzed that data to reach their conclusion.

“PET has a good balance between carbon, hydrogen and oxygen to simulate the activity in ice planets,” added Dominik Kraus, professor at the University of Rostock. “The effect of the oxygen was to accelerate the splitting of the carbon and hydrogen and thus encourage the formation of nanodiamonds. It meant the carbon atoms could combine more easily and form diamonds.”

While there’s no exact number of how many planets can form diamonds in their atmosphere, the researchers hope to conduct further experiments using ethanol, water, and ammonia.

“The fact that we can recreate these extreme conditions to see how these processes play out on very fast, very small scales is exciting,” said SLAC scientist and collaborator Nicholas Hartley. “Adding oxygen brings us closer than ever to seeing the full picture of these planetary processes, but there’s still more work to be done. It’s a step on the road towards getting the most realistic mixture and seeing how these materials truly behave on other planets.”

The group’s full study can be seen in Science Advances here.