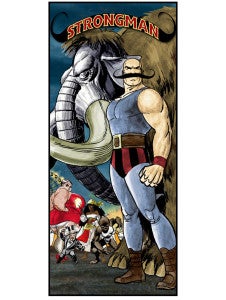

A generation of fans will remember Jon Bogdanove as the artist who launched Superman: The Man of Steel with Louise Simonson, and then stayed on the book for almost its entire run.Since then, he hasn’t had a mainstream comics gig with that kind of visibility, prompting some fans to react with surprise when he returned this week with a new Kickstarter project: Strongman, the tale of a 1920s circus strongman who assembles a group of sideshow performers into a kind of almost-superhero team.Bogdanove hasn’t been gone, though; he’s mostly been doing art for DC Comics’s licensed products, so it’s just harder to spot. He joined ComicBook.com on the eve of San Diego Comic Con International to talk about his experiences at the Big Two and working on his own with his son to develop Strongman, a property originally conceived as a video game.You can check out the trailer directly below, and the Kickstarter campaign here. Check back later in the weekend for more from Bogdanove about his time on the Superman titles.

Exclusive: Superman Veteran Jon Bogdanove Discusses His New Book, Strongman

A generation of fans will remember Jon Bogdanove as the artist who launched Superman: The Man of […]