Videos by ComicBook.com

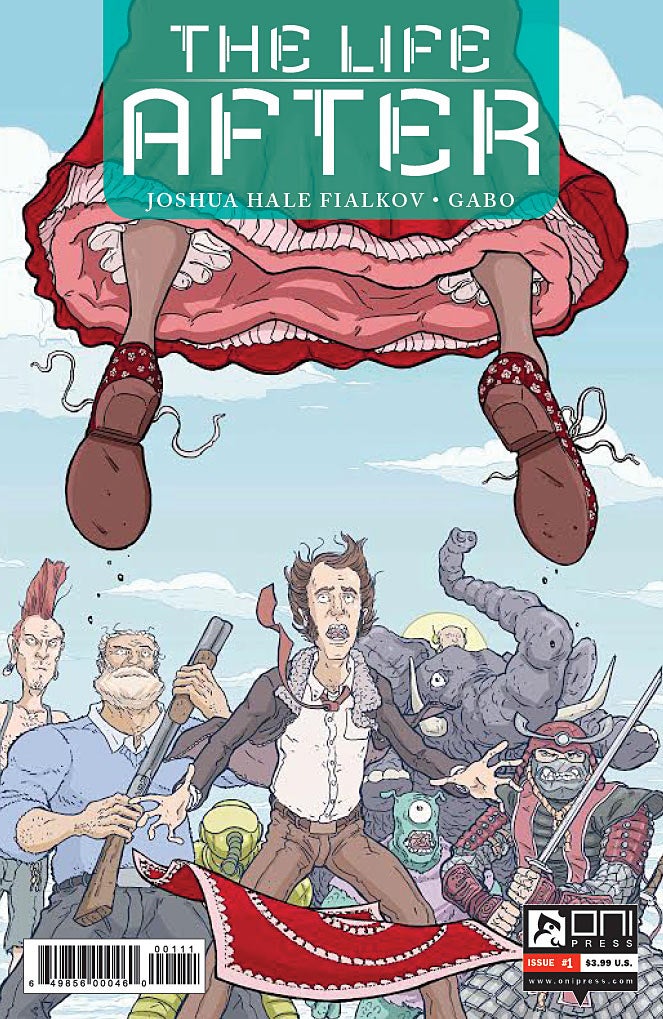

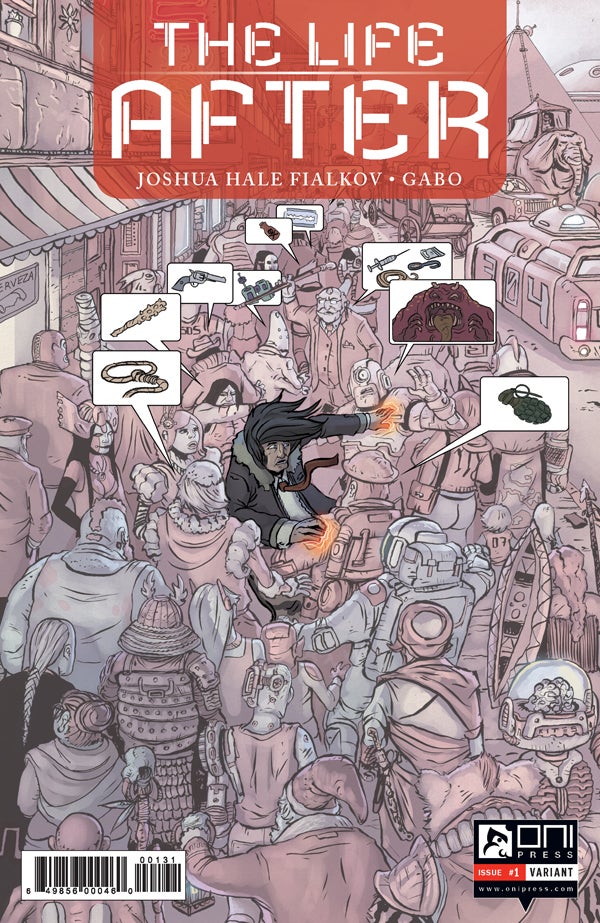

Here’s how the solicitaiton text describes it: “In an infinite city built on infinite sadness, there is one man capable of breaking free. He will go through Heaven and Hell to save us all. Literally. A fantastical coming of age journey through the afterlife and beyond from Joshua Hale Fialkov and breakout artist Gabo.”

Fialkov joined ComicBook.com to talk about the series. Here’s how he described it.

Note: The Life After #1’s final order cutoff is Monday, so let your retailer know this weekend if you want to pre-order a copy.

Joshua Hale Fialkov: A little bit, yeah. I see that.

This book is different for me because I like contained stories. If you look at my creator-owned work, even though The Bunker is a sprawling story tht has global consequences, it is very much insular. It is very much these people and how they react to the world outside of them.

What I wanted to do with Life After was I wanted to do a book that still had that character at its heart, that small cast at its heart, but is about bigger things and bigger concepts and I think looking at the work of a Grant Morrison or Garth Ennis or Brian K. Vaughan, those guys who sort of do that, is where a lot of these ideas started.

And it’s a kind of book. It’s this sort of sardonic epic adventure is sort of the genre, you know? [laughs] But the idea of telling that kind of story is so appealing to me becuase I hadn’t done it before and it’s fun. It’s just fun to tell that kind of story. I think I did it a little in I, Vampire; I think we started to get there in I, Vampire before the rug was pulled out but with this it’s nice becuase it’s built from the top to be a place for me to talk about what I want and what I think. The legend goes that if you look at those original Vertigo books, the big Vertigo books, each of them were a playground. Transmetropolitan is clearly a playground for Warren Ellis. It has a story and it has a through-line, but it’s clearly a “what am I interested in this month?”

Preacher is the same way for Garth Ennis and Sandman is obviously that for Neil Gaiman. Yes, there’s all the stuff, the big, broad story stuff, but it’s really just a place to get to explore your thought and get to explore your feelings and it’s just such a fun way to tell a story. I would guess that’s what you’re picking up.

Fialkov: Nice [laughs]. They just did that — it did not do well at the box office. That was not a banner weekend for [Edge of Tomorrow]. I want to see it, too.

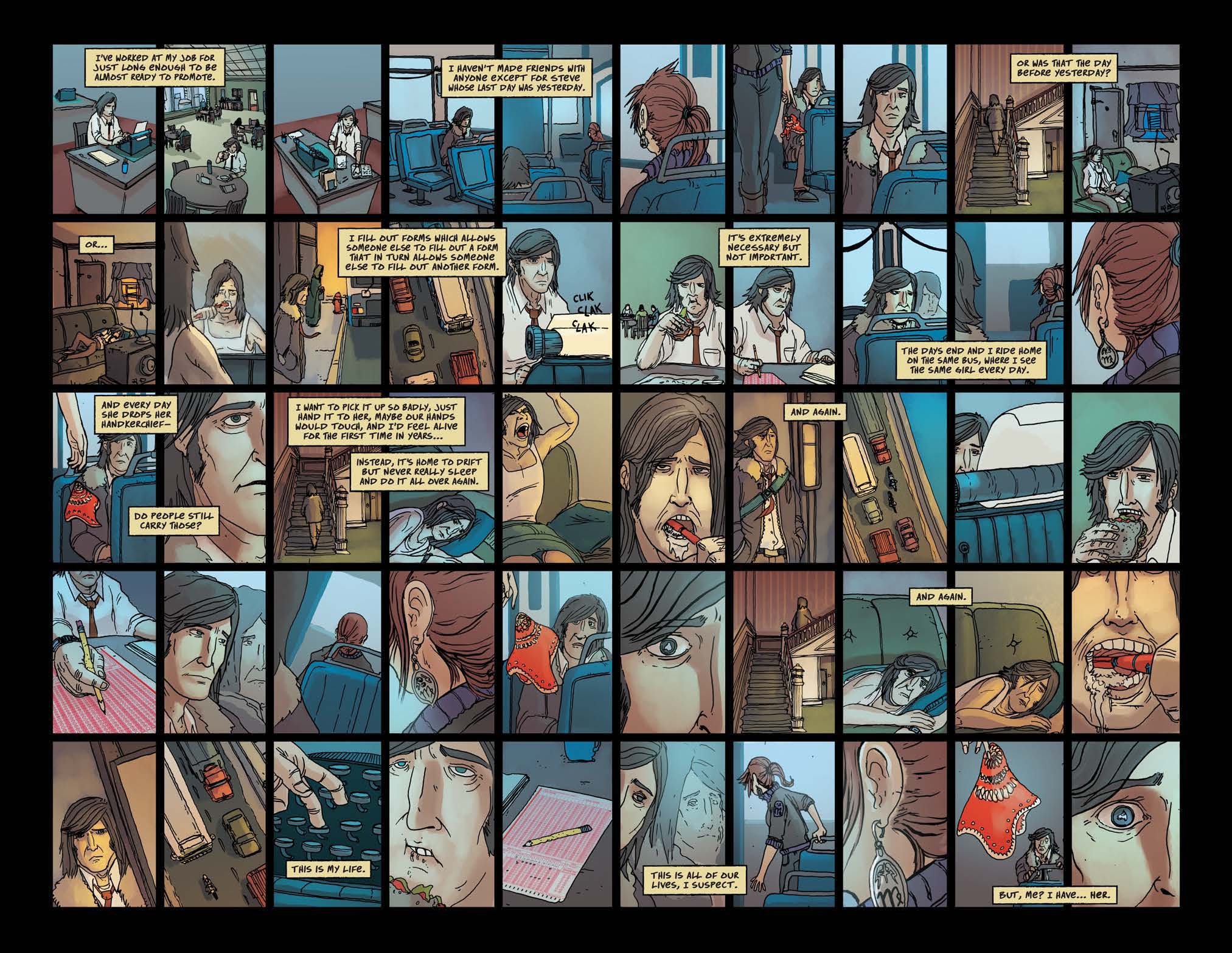

Yeah, but again if you look at the first five pages of pretty much anything I’ve written in the last five years, I have a crazy awareness of that — of writing for the previews. It’s not even writing for the trade — it’s the opposite. It’s writing knowing that there’s going to be five pages on the Internet, and those five pages are all you have to try and sell a book.

And that’s always going to be true but what I like about this book and the things we’re trying to do is that as the book grows and as the book moves, there’s going to be more. There’s going to be more that you see and there’s going to be more layers that get unwound. So every issue becomes layers of its own little self-contained piece, all building toward this bigger story.

So it really is about starting at one step. He’s going on this journey and this journey’s going to be epic and it’s going to be big and it’s going to take a long time, but to get on his way, he’s going to have to break out of this thing first.

Fialkov: Yeah, I like the idea of point-of-view. You as a reader are being taken into the place of the main character and I think it’s one of the things comics do really well — we become ciphers. It’s one of the reason Spider-Man works really well; because we see ourselves under the mask.

And I think you can do that — especially with Gabo’s art because it has this sort of distinctly indistinct feel to it where he looks like a person…you feel like you know Jude. But there’s also something really self-referential about it because he feels like a person, he doesn’t feel like a comic book character. He feels like a real guy, a guy you’d see on the street. And so you kind of get sucked into it.

And letting you as a reader discover what’s going on as Jude does is one of the pleasures of the book.

There’s all kinds of crazy, awesome, beings that don’t fit really into the world where your main character is watching a tube TV at the start. At what point did you think, “In purgatory, there’s gonna be some guy riding a bubble on top of an elephant?”

Fialkov: That’s all Gabo. He just goes crazy. Gabo and his imagination is amazing. But part of the thing that appealed to me about this is that I love anthologies and I love the ability to tell short, compelling morality tales over the course of a couple of pages. And by having the afterlife be a mash-up, I think it gives us the freedom to try to explore.

So we have conversations like, “What do you want to draw this month?” And he’ll say a caveman, so I find a way to do a caveman story — to fit in a two-page caveman flash. Or he’ll say he wants to draw aliens or a gorilla man. And so you have that freedom.

And the idea is that the afterlife has the same problem — that someone came in and sold them this big system and they put this system in place and this system is going to last us forever — and that system has just been running perpetually forever. And it’s starting to break down and it’s starting to not work right. And the idea of that is that we take a 2,000-year-old document in the New Testament or a 5,000-year-old document in the Old Testament or a 225-year-old document in the Constitution. We take all of these things that we’ve evolved past. We’ve evolved and we have new problems that none of these documents can solve. But we cling to them and we cling to the dogma of them, rather than say our world is far more complicated now.

There is no way that the founding fathers said, “Well, I’m sure it will be okay if people have guns that shoot 300 rounds a minute. How could that be a problem?” They didn’t know — they just knew we needed guns in case someone invades us — in case Canada gets randy, we need guns.

So there’s all these things that we’re so tied to old systems that we can’t move forward.

And that’s the fun stuff. That’s how we get to start finding out there are all these layers and how this elaborate set of rules is actually, people use it as a pillow when the fact is it’s actually a cage.

The fun part is that I get to look at the art and say, “Oh, now I have to explain that!” That’s one of my favorite parts of comics. There’s an issue of The Bunker that came entirely out of Joe saying to me, “Hey, Grady’s in the bunker this whole time before anybody else, right?” And I say yeah. “And he’s done all this stuff, right?” Yeah. “The bunker was buried.” Yeah. “So how the f–k did he get out?”

And there’s a second where I’m like “oh, s–t! Oh, God!” And he’s like, “Well, I just figured there’s a second door.” Then you do a whole issue about the second door. That’s the best part is that it’s collaborative and we’re building something together that grows and changes and that — if I switched artists on the books, if Joe was drawing The Life After and Gabo was drawing The Bunker, those books would be completely different becuase they would have to be.