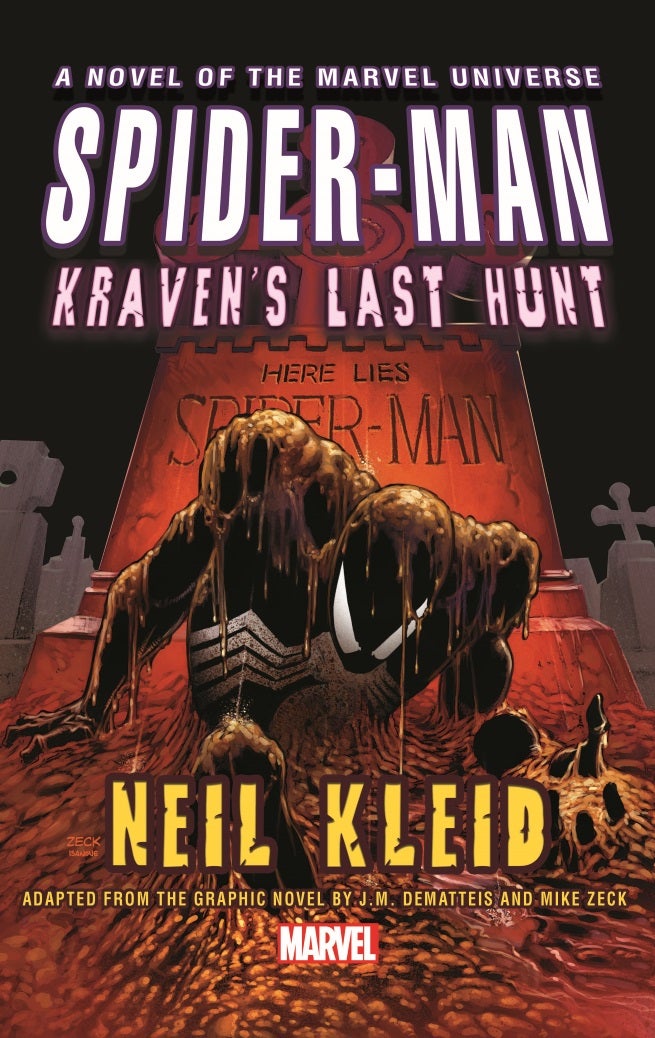

The iconic Spider-Man storyline, “Kraven’s Last Hunt” (by J.M. DeMatteis and Mike Zeck) is getting a brand new spin as writer/artist Neil Kleid has adapted the 1987 comic book arc into a novel as part of Marvel’s Prose line.

Videos by ComicBook.com

Kleid, author of the graphic novels Ninety Candles and Brownsville, has been a published writer/artist in the comic book/graphic novel medium for more than 10 years, having also worked with such publishers as Marvel, DC, IDW, Dark Horse and Image. He took some time to answer a few questions about his new Kraven’s Last Hunt novel, which will be available wherever books are sold on October 1.

As someone who has worked extensively in sequential art, what were some of the overall challenges in adapting a graphic story into prose?

Well, first and foremost, when writing prose one cannot depend on amazing art to distract from any poorly composed paragraphs or passages!

Honestly, it comes down to having to paint a picture with words rather than allowing a fantastic illustrator to set your scene. When you’re scripting a comic book a panel description might be as simple as “Panel 1. Spider-Man enters a warehouse through the window.” In prose, you have to describe the warehouse — how far up is the window? Did he push up the window or push it in? Was it already open? Every story decision needs vivid, choreographed detail. True, prose allows more room in which a writer can lay the scene — you’re talking about 22 pages, maybe 5-6 panels per page in comics, while prose can spread out to 65-75K words/approximately 300 pages. Thing is, though, you’re trading elbow room for the visual safety net of illustration. Want Spidey to muck about the sewers searching for Vermin? Be prepared to describe every inch of that sewer, evoke smells and atmosphere, and choreograph every step of the chase and inevitable battle beneath the city streets.

The nice thing about adapting a six-issue mini-series into prose — unlike approaching it from the other direction — is that you gain that room in which to play. The problem is that you have to fill that room, and when dealing with a specific storyline a writer might find the original source material falling short of having enough to comfortably fill the space. We had that issue with Kraven — a gripping story that often employed silent, repetitive, poetic visuals and allegories — and the editors and I found the need to rework a bit of the story, as well as borrow from moments before and after, in order to create a fully fleshed-out novel that didn’t feel brief or fall short of the mark.

What is it about “Kraven’s Last Hunt” that you think makes it a worthwhile comic book story to be adapted into this format?

Personally, I’m a huge fan of psychological exploration, getting into a character’s head and really understanding what he or she is thinking during the course of a literary journey. Kraven’s Last Hunt, to my eyes the first real story to do so for a well-established, mainstream super-villain, opened the door to Kraven’s mind and presented the perfect opportunity for a prose novel to dig further. Even better, this is a story that offers four unique and emotionally divergent points of view — Kraven, Peter, Vermin and Mary Jane — and while the six issues touch on each one, they did not allow the space to move about inside each character’s head and juxtapose, say, Edward Whelan’s internal struggle with Vermin against Mary Jane’s internal struggle with herself. It begged for a deeper dive. It yearned for someone to come along and really turn Kraven’s journey over in his or her hands, stare at it from all sides, and reveal how the Hunter was more than just a man in a lion’s mane suit — he was a son, an orphan, a frustrated champion, a beast, a man, and so much more.

Look, I’ve been a fan of Last Hunt since I first read it in the Eighties. This was a few years before the Killing Joke, before Alan Moore tore apart the Joker’s veneer and dissected a super-villain. And, for heaven’s sake, it’s Kraven the Hunter we’re taking about. At best (before Last Hunt, of course) a third-rate, lesser-known member of the Sinister Six, the guy who threw trained lions at Spidey and tried to trap him in a cage. I mean, it’s not The Green Goblin’s Last Hunt, or that of Doctor Octopus. He’s a dude in a loincloth. No one was expecting much.

But then DeMatteis came along and gave this blank slate character a story. He invested within Kraven a sense of purpose, history and most importantly, both obsessions and flaws. DeMatteis (and Zeck, of course, through use of dark, eerie, often disturbing visuals) made readers look twice at Kraven the Hunter and see beyond the ridiculous get-up and wild animals to peer within at a drive and yearning need to prove himself and redeem his name. And the lengths he might go to do both.

That, to me, is fascinating. That, to Marvel, is a story worth exploring.

And, of course, Spider-Man. Power. Responsibility. Wheatcakes. You know.

But, Kraven!

A lot of Spider-Man/comic book fans believe “Kraven’s Last Hunt” is one of the greatest Spider-Man stories of all time. Does the story’s iconography provide any added pressure to you for a project like this?

No, no pressure at all.

Dude, of course there’s pressure. Heck, I’m one of those fans and speaking as such, if this Kleid guy screws up my favorite Spider-Man story there’s going to be hell to pay.

Here’s the thing: I’m a graphic designer by day, and often as a designer you spend a great deal of time locked in your head, throwing text boxes and vector graphics about a page or design, convinced that the web site you are working on is without a doubt the Sistine Chapel of web sites. Your family agrees, as do your colleagues. Your bosses shower praise on the finalized web site design and sing hosannas from the rooftops, proclaiming you King of All Web Site Designers.

And then it goes out on the internet. And on the internet there are people who don’t know that you’re a genius or that your friends, family, bosses and clients have crowned you King of All Web Site Designers. Because, let’s get this out of the way here: Design is Subjective.

And, according to the internet, so is everything else.

So, sure, even if the book is one hundred percent faithful to the original source material (it’s not) and gets a gold Merry Marvel Marching Society stamp from Spider-Man himself (Spidey’s real, kids! He’s real in our hearts!) you can bet someone out there — creator, critic, casual reader, or fan — will make sure I know about a specific detail I changed, forgot, ruined or defaced.

And that’s fine.

My goal was to take everything I loved about Kraven’s Last Hunt, translate it into the best possible prose adaptation that I could muster, add a few of my own personal touches and ensure that the story was presented in the best possible manner for both new and devoted fans. My hope is that the folks at Marvel and I made that happen, and that fans of the original issues find both nostalgia and something new, while new readers are exposed to a wonderful, ground-breaking story they’ve never read before.

But nervous? Not me. I’m too busy biting these fingernails to the bone to be nervous.

While developing this prose project, did you discover anything about the comics (themes, plot elements, characterization, etc.) that you had never noticed before? If so, how did you hit upon and then develop those ideas?

Before the book’s editor, Stuart Moore, and I first met to discuss the book, I jotted down a handful of recurring themes that I noticed on my initial re-read of Last Hunt. What I loved about this book is that each of the book’s main characters — Pete, MJ, Kraven, and Vermin — connects to those themes in ways that truly enhance their journey throughout the story. Chief among those themes is that of “coffins.”

All four of our POV characters consider themselves a victim of some kind— even Kraven, the villain (every villain is the hero in his/her own story, so…). But more important than their victimization is their isolation of one form or another. Each exists in a coffin of his or own making: Peter’s coffin is, of course, literal…but long before Kraven sticks him in the ground, Pete has been boxed by guilt and responsibility (as well as eventually, a coffin of madness when he questions if he’s still in the grave). Kraven’s is a coffin of honor, and of failed purpose; the hunt helps him escape it to find peace and happiness in another. MJ’s coffin is one of secrets and fear, hers and Pete’s, one she can escape anytime she chooses but has to find reasons to climb back inside. And finally, Vermin lives in a coffin of pain, defeat and darkness, afraid to come out for fear of getting hurt. When writing the novel, I really wanted to play on this sense of living in your coffin, what that means for each character.

There are a number of other themes throughout the prose, but only two more are worth mentioning here: “ghosts” and “truth.”

“Ghosts” is a loose one, and I’m not sure “ghosts” nails it, but it’s essentially about making decisions and being haunted by those decisions. For Pete it’s the people he’s let die or get hurt by his life as Spider-Man; for MJ it’s the ghost of Gwen Stacy, and as the narrative continues, the ghosts of the life she will lead if she stays or walks away from a life with Peter Parker. Kraven’s ghosts are those of his family, his mother in particular, and all his failures since arriving in America. Finally, Vermin is haunted by the man he used to be, as well as by the pain and persecution he’s received at the hands of cops, society and superheroes.

“Truth” really goes hand-in-hand with “honor,” specifically relating to Kraven’s mission and the change that happens from when he begins to undertake it to the end of the book, to the point of no return. A key, telling line “I’ll show him the Truth. And when we finally share it, we’ll both be free.”

I could dissect this story all day and night, but there’s only so much space on the internet to contain it, I’m sure. But the one thing I do want to mention is how much writing this book made me completely understand Mary Jane Watson in a way I never had before. We talk about strong women in comics and what that means, and I think what makes MJ one of comics’ strongest women is that quite honestly, she doesn’t have all the answers…and that’s all right. She doesn’t have Lois Lane’s no-nonsense, take-no-prisoners attitude. She has no powers on which to rely like Sue Storm Richards, Wonder Woman, Carol Danvers and so many others. Like Peter Parker, Mary Jane has doubts and fears and often makes (and has made) terrible decisions, and it is the process by which she comes to those decisions which makes her a fully formed character with real hopes and needs and flaws and that both fascinates me and makes her all the more intriguing. MJ has been tested. She has walked away. She has returned. She has walked away again. And each time she appears on our page we learn something new about her, something that makes her all too real and relatable. This story allowed the editors and I to really delve into MJ’s struggle and learn what being Spider-Man’s significant other actually means. How does it affect her? How does it affect the world around her? When her boyfriend — a man she just learned goes out night after night with a giant spider on his chest to fight, oh, say, Galactus — disappears for two weeks, what does that do to her mental and emotional state?

By the way, I find it interesting that the first mention of Mary Jane in a Spider-Man comic (“I’ve arranged a date for you with a lovely girl!”) happens to be Amazing Spider-Man #15, Kraven’s first appearance. Face it; I hit the jackpot with this story.

Personally, what’s your favorite part of the comic story? There are so many memorable moments in “Kraven’s Last Hunt,” is there one that you find more enduring than the others?

“Hey—how come you’re looking at me like that? Don’t you remember me? Ned Leeds?”

Peter’s journey back from the grave was easily one of the more compelling sections of the story to my eyes. But that first contact with Ned — especially after the previous year of Spider-Man comics, after the gang war and having been embroiled in the mystery of the Hobgoblin, seeing Ned upright and well dressed simply blew me away. One of my greatest joys writing this book was being able to rope Ned into the larger narrative, to connect the impact and effect the Hobgoblin had on Spider-Man to the impact and effect Kraven’s hunt would have on him, as well.

But, yeah. Ned Leeds crumbling to dust a la Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade? One of many, many excellent moments.

What do you ultimately hope to accomplish with a project like this? Are there other comic book stories that you think would make for worthwhile prose adaptations?

As I said earlier, I’m mainly hoping that fans of the original issues enjoy a much-loved and seminal storyline in a whole new way, while new readers are able to experience DeMatteis and Zeck’s gripping tale of truth, doubt, love and redemption through my meager words. Of course, I’m also hoping that the original creators feel I did them justice, and the folks at Marvel enjoy it enough to bring me back for more. Can you imagine a prose adaptation ofThe Infinity Gauntlet? That one might be a bit daunting to tackle. My holy grail would probably be a prose adaptation of “Avengers: Under Siege”, the storyline in which the Masters of Evil storm and take over Avengers Mansion. You could get some interesting and diverse POV characters from that one, including Jarvis and Baron Zemo.

Failing that, I’d be overjoyed to swing above Manhattan one more time and either pit him against the Sinister Six … or the Sin-Eater … or heck, I wouldn’t mind putting Pete back in the ground once more time and letting a … superior Spider-Man take the web-shooters for a while.

You know what they say: write what you know.