Marvel Comics have always been political. The premiere issue of Marvel Comics, published in 1939 and featuring the Sub-Mariner, illuminates how weapons testing by humans drove the Atlanteans into conflict with the surface world. An ecological disaster precipitated by apathy and Cold War-era atomic experimentation drives one race of beings to declare war on another race. The Skrulls introduced in Fantastic Four #1 (1961) are archetypal shapeshifters and acted as a surrogate for the Red Scare, the fear of Communism and foreign infiltration that gripped America after the USSR’s Sputnik satellite sailed over US skies. And the character of Marvel’s iconic Captain America, empowered by a Super Soldier Serum to fight the Nazi menace, was prompted by the German war machine’s bid to create a race of supermen to fight tirelessly for the Third Reich.

Videos by ComicBook.com

In advancing heroes and heroines that reflect under-represented groups in the pages of Luke Cage, Ms. Marvel, and Uncanny X-Men, or tackling societal issues such as political corruption, gender discrimination, and classism, Marvel Comics has produced some enlightening critiques of our political theater and the human condition. Let’s take a quick look at 7 occasions when Marvel Comics took it to the streets.

Peter Parker the Spectacular Spider-Man #9, “The Flames of Protest”

In 1977, Bill Mantlo, Sal Buscema, and Mike Eposito harnessed the power of protest and perennial issue of systematic racism to introduce Marvel Comics’ White Tiger to the Peter Parker the Spectacular Spider-Man storyline. Back on college campus at Empire State University, Peter encounters a group of protesters voicing opposition to the university’s plan to close down Night School classes, attend primarily by working-class students from minority populations. Citing greed and racism as the closure affects people of color, Black and Hispanic students bear protest signs reading “Without an education, We’re second class citizens” and “Abre las puertas! Open the doors!” Surrounded by campus security, one protester wryly remarks, “How come you can afford cops but you can’t afford us?”

Mass protests, racial overtones, political activism resonate strangely in this decades-old comic as Columbia University in NYC is, ironically, the model for Stan Lee’s fictional Empire State where student protests catalyzed. The past year has seen political unrest and harsh reprisals consume Columbia University in a manner similar to scenario depicted in PPTSS 48 years ago. Events repeat and the world needs heroes. As White Tiger mused in the 1970s, “Everything we won in the ’60s is being taken away—its the same old fight all over. We need a symbol, something to rally around. One of our own…to give us pride.”

Wolverine #41 (2006), “The Package”

Wolverine comics are often darker and more graphic than other Marvel books, due in part to the moral ambiguity of the antihero and his willingness to fight against overwhelming odds, regardless the cost. Wolverine #41 from 2006 embodies those grim tendencies and rarely has such a provocative tale been accompanied by such equally astonishing artwork. Writer Stuart Moore and artist C.P. Smith have achieved the unlikely in this harrowing masterpiece entitled “The Package.”

As the story sets out, Black Panther has enlisted the Wolverine for a job in the Free Republic of Zwartheid in Africa, a clandestine mission behind enemy lines to secure a package. Described as the “worst country on Earth,” Zwartheid was torn asunder by decades of civil wars fostered by Western corruption, mass slaying, and forced amputations, while thousands of its youth were forcefully conscripted as child soldiers. As Wolverine stalks the compound, the narrative relates even more horrific acts such as rape as a weapon of war, the deliberate infection of victims with HIV, and genocidal bloodshed. It is a bleak and daunting tale that challenges readers to confront the reality of conflict and societal collapse.

Ultimately, a reluctant Logan is waylaid by a gang of hostile child soldiers armed with automatic weapons. Claws unsheathed, he shields the mysterious package—revealed to be the infant child of the Zwartheid’s fallen leader and the desperate nation’s last hope for the future.

A Moment of Silence – 9/11 Tribute (2002)

A Moment of Silence – Saluting the Heroes of September 11th, with an introduction by Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani, was published by Marvel Comics after the fall of the World trade Center in 2001. The charity project featured four creative teams with talents including Kevin Smith, Brian Michael Bendis, John Romita Jr., and Joe Quesada. In its somber pages, A Moment of Silence portrays the courageous actions of real heroes—ordinary people, firefighters, family members, and concerned citizens acting selflessly in the face of utter horror and destruction.

One piece by Bill Jemas, Mark Bagley, and Scott Hanna highlights the sacrifice of Anthony Savas, a longtime building inspector for the Port Authority, who ran into the firestorm to save the lives of people he had never met. These tragic stories are told absent of dialogue with images of human compassion and the terror that leveled the tallest buildings in the world speaking untold volumes.

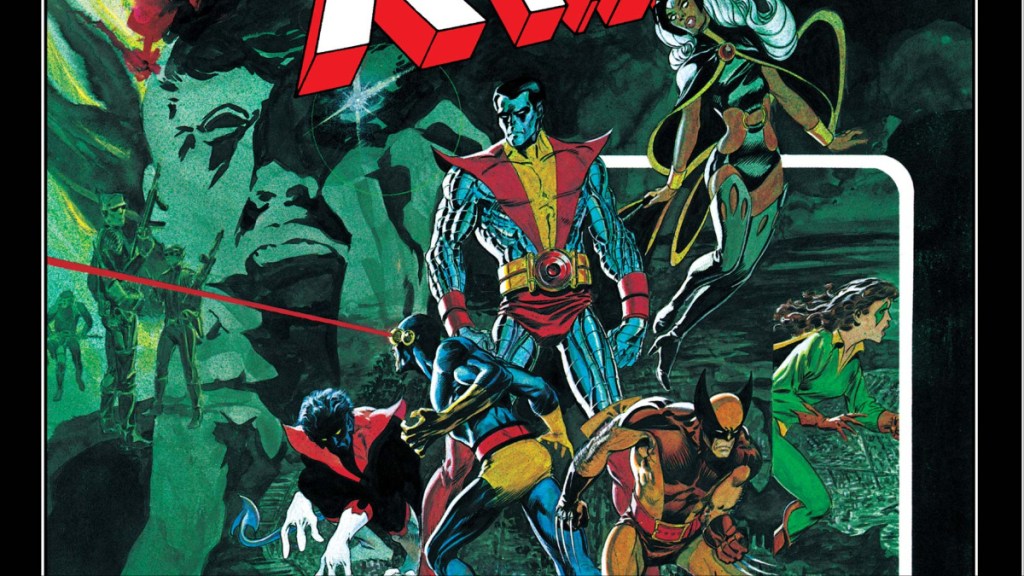

God Loves Man Kills (1982)

English writer Samuel Johnson remarked that “religion is the last refuge of a scoundrel” and the X-Men graphic novel, God Loves, Man Kills from the early 1980s explores that notion through the lens of bigotry and intolerance pervading American society in the late 20th century. Mutants in the Marvel Age are no strangers to oppression and the X-Men are the ultimate analogue for the persecuted, whether that be discrimination against race, gender, sexuality, religion, or class. God Loves, Man Kills, written by Chris Claremont and illustrated by Brent Eric Anderson, exemplifies the mantra that the X-Men “protect a world that hates and fears them.” When religious zealotry as wielded against the most vulnerable in society and conventional means prove insufficient , the X-Men must once again take the vanguard in the fight against fanaticism.

Brandishing harsh vitriol in the guise of Biblical verse, a calculating and manipulative evangelist, Reverend William Stryker espouses violence against the mutant community, preaching that “any mutation comes not from Heaven but from Hell.” With the eerie Nightcrawler as his hobgoblin and the mutants his scapegoat, Stryker’s poisons the minds of his followers through piety and indoctrination, using conspiratorial rhetoric on the naive and the gullible. Religious inquisitions and spurious witch-hunts are the tools and tactics of demagogues and villains, and God Loves, Man Kills illustrates why they are to be resisted—by any means necessary.

Civil War (2006)

Civil War is a celebrated story-arc that explores righteousness and civil disobedience, as well as the perils of conformity and appeasement. As schismatic as the Mutant Registration Act was, turning mutant against mutant, so too was the Super-human Registration Act (SRA). Divisive and politically motivated, the draconian SRA was meant to monitor augmented humans and mandated heroes unmask or face incarceration for illegally wielding weapons of mass destruction. Consider the effect of this Act on an innocent in the line of fire such as Aunt May. One can only imagine the results if the maniacal Green Goblin learned that Peter Parker was his arch foe, Spider-Man and he has family back home.

In Civil War (2006), Captain America’s intriguing lean into the Bill of Rights and freedoms inherent in the United States Constitution—choosing resistance over blind allegiance to country—puts him on a collision course with Tony Stark and the formidable strength of the State Apparatus. With the government hounding his heels and Stark-tech spying from the skies and streets, the Star-spangled Avenger and his cadre of rebels fight for the ideals that unite all Americans—at least in the comics.

Alpha Flight #106 (1992)

The Canadian superhero group, Alpha Flight is a diverse cast of characters including a spellcasting shaman, an actual Sasquatch, and the brash and highflying Northstar, one of the group’s mutant twins. Spinning out of Chris Claremont and John Byrne’s X-Men, the team tackles reprobates and even-doers in the Great White North, sometimes hitting stateside to coerce or kidnap their erstwhile ally, Wolverine. As uncanny as their American counterparts in Westchester, the characters in Alpha Flight allow writers and artist to explore uncharted territory and test boundaries such as mysticism, identity, and for the first time in comic history, homosexuality in art and society.

Set during the hysteria of misinformation and baseless social stigmatization surrounding victims of the AIDS epidemic, the cover to Alpha Flight #106, “The Walking Wounded,” circumspectly promises to deliver “Northstar as you’ve never known him before.” An abandoned child is discovered by the mercurial Northstar and, after being diagnosed by doctors as HIV positive, the hero adopts the sick foundling. Northstar, a.k.a. Jean-Paul Beaubier, is wealthy man of celebrity status as well as a national hero and the media seizes on the story. Ignoring the countless victims of HIV in the gay community, the media chooses to sensationalize the “innocence” of the child, fawningly announcing that “all Canada has embraced the plight of this AIDS-stricken infant.”

One viewer, a crestfallen father whose son had died a pariah from AIDS, takes issue with the media circus and with Northstar himself. The father’s indignity and frustration boils over and, in irrational rage, he assails the mutant. “My son, Michael was a victim of AIDS as well. But he was gay so people didn’t afford him the luxury of being’ innocent.’ There were no press conferences, no fund-raisers, no nightly news updates. He was just one of thousands who died of AIDS last year.” Michael had died unceremoniously, a causality in a war of misinformation and neglect.

In an unprecedented moment in Marvel history, Northstar proclaims, “Do not presume to lecture me on the hardships homosexuals must bear. No one knows them better than I. For while I am not inclined to discuss my sexuality with people for whom it is none of their business—I am gay!” This admission frees Northstar to be public with his sexuality and, in valuing and accepting himself, allows him to use his renown in defense of a closeted and unprotected minority. With this revelation, Northstar can defiantly declare that “AIDS is not a disease restricted to homosexuals” and “it is past time that people started talking about AIDS, about its victims, those who die and those of us left behind.”

Legacy Virus

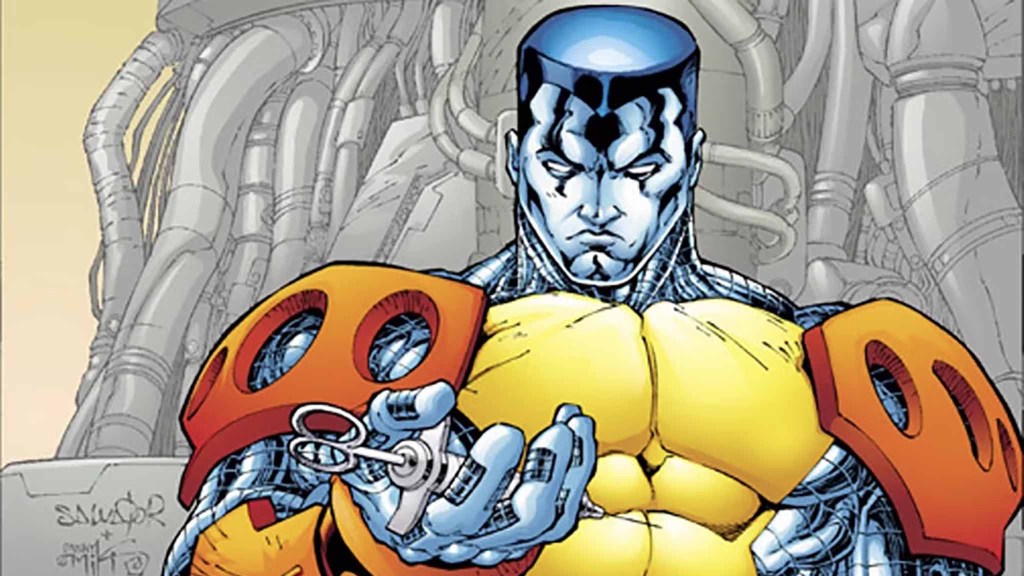

The Legacy Virus story arc spans several years in Marvel history, beginning in X-Force in 1993 and coursing through the mutant population until the early 2000s. A deadly pandemic that initially affected only those carrying the X-gene, the Legacy Virus later mutated into a virus capable of infecting humans, as well. Hundreds of mutants fell to victim to the Legacy Virus until Colossus of the X-Men sacrificed his life in Uncanny X-Men #390 to save the world for humanity and mutantkind. In human history, this fictional virus simulates the frightening reality of the HIV outbreak and the AIDS epidemic beginning in the 1980s that would claim the lives of more than 42.3 million worldwide.

As is the case with real-world pandemics and the transmission of illness, the Legacy Virus begins as a mysterious sickness, striking seemingly at random individuals. As infection rates climb and mass causalities mount, an anxious and ignorant society seeks out scapegoats and finds succor in conspiracies. With a torrent of misinformation whirling about, some begin to consider that the Legacy Virus may have been created to eradicate mutantkind—even as the virus mutates and spread to the human population. And in this struggle for survival, two communities that might have aided one another embrace division and devastation for want of compassion and understanding.

What other Marvel comics did you think were political? Let us know in the comments!