Have the Judges been doing more harm than good to Mega-City One? Do they care? Those are questions posed in “A Better World,” the new Judge Dredd storyline from writers Rob Williams, Arthur Wyatt, and artist Henry Flint kicking off in this week’s 2000 AD Prog 2364. Picking up on threads that Williams and Wyatt have weaved throughout their recent Judge Dredd stories, “A Better World” sees the Judges confronted with data that seemingly proves their relentless war on crime has only served to perpetuate an endless cycle of conflict between Mega-City One’s citizenry and its authority figures, the Judges.

Videos by ComicBook.com

This might seem obvious. Judge Dredd’s stories have always had a darkly satirical undercurrent to them, after all, and the Judges are unabashed fascists who have stomped out pro-democracy movements in the past. But what happens when it isn’t agitators from outside the system challenging the Judges but one of their own?

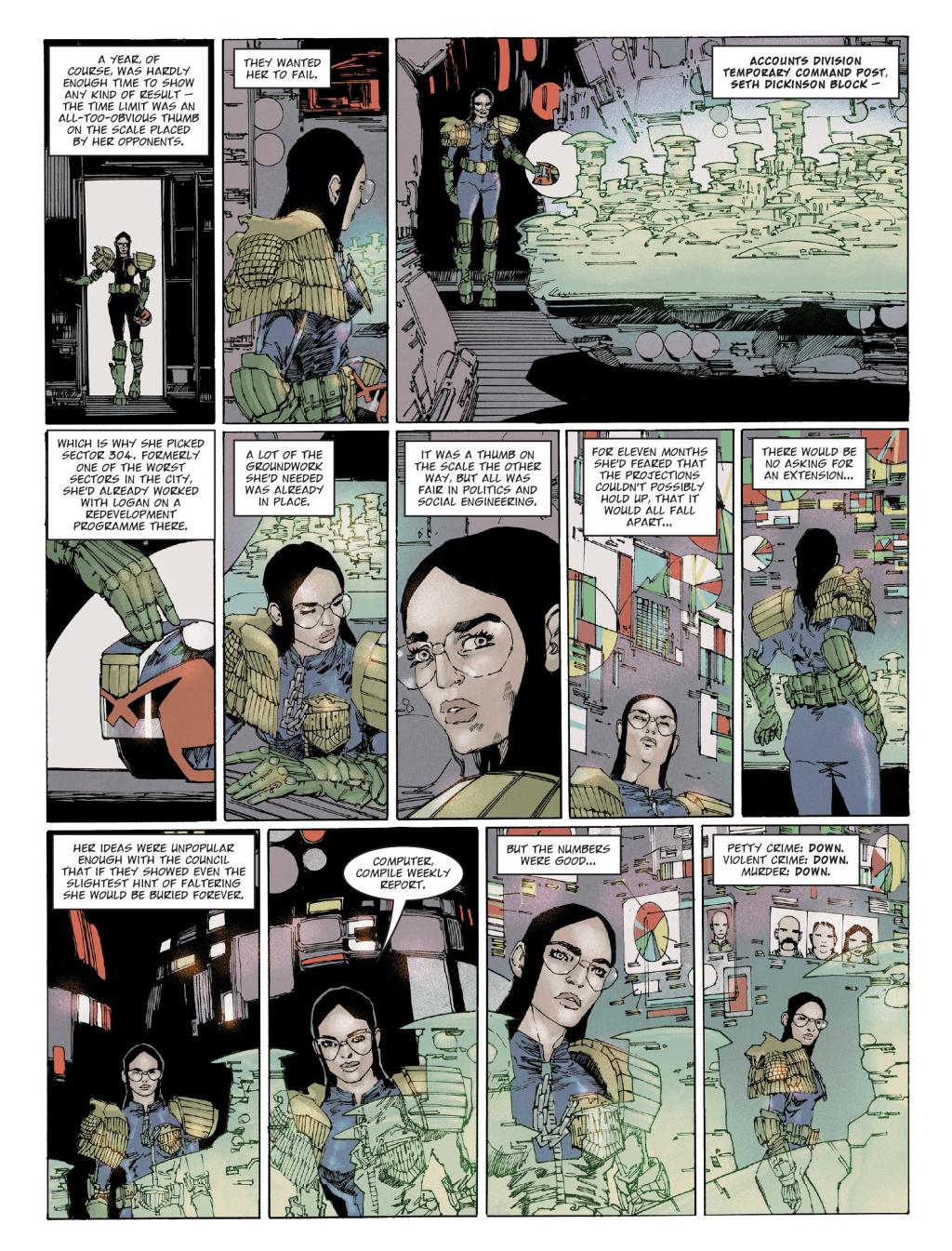

Judge Maitland, a forensic accounts Judge, studied one sector of Mega-City One, where she was allowed to take money from the Judge’s budget and reallocate it to education. Crime dropped. Now what?

ComicBook.com had the opportunity to ask Williams and Wyatt a few questions about the story. Here’s what they had to say, along with a few preview pages from the first chapter of “A Better World.”

What’s the genesis of this story? Was there a lightbulb where you made that connection between “defund the police” and Judge Dredd?

Arthur Wyatt: IIRC, that was straight out of Rob’s head when I suggested collaborating on a Maitland story, around the time End of Days was coming together. We’d both used the character in different ways – I had her as the hotshot forensic accountant bringing down global criminals by tracing financial trails, Rob brought her into the political intrigue of the small house. Rob’s suggestion that we run the story after the upheaval of his story seemed a good one – with everything up in the air she could take a hard look at what worked and what didn’t and come to new conclusions, and because she’s a big picture person working with overarching systems we could have her hit some big themes – in this case that the brokenness of the city, something core to Dredd’s world, was fixable and not inherent.

And the nature of the character is that, once she figures that out, she’s going to dig away at it whatever the consequences, so there’s going to be drama…

Rob Williams: My memory’s terrible, but it just seemed a natural way to go. I’d written Judge Maitland in a bunch of my Dredd stories, and Arthur asked if I minded if he used her in a storyline of his, and I think we got talking about collaborating on just one story. That had permutations at its close, and then we somehow decided to tell this long-running Judge Maitland story in very occasional chapters. My work on Judge Dredd tends to happen in this quite organic way – you write one story, and a plot thread in it suggests the next story, and so on. Which makes it sound like there’s this amazingly detailed plan running over years when often it’s not the case. It’s usually ‘oh, there’s that plot thread, we’ll come back to that at some point,” and it might take a year or two to do so.

I think I was somewhat wary of writing a ‘Defund the Police’ story in Dredd’s world when the riots were taking place in America. It just seemed a little too on-the-nose. But there’s been some distance since, which makes it easier. Makes it more about the ideas at play here.

Judge Maitland being a very good, brave accounts Judge, and running numbers and seeing the obvious – that the Judges on the streets of Mega-City One are fighting a war on the citizens every day, and that isn’t sustainable – that’s just something that seemed ingrained in her character. And how Maitland’s been built by writers like me and Al Ewing and Arthur – she’s going to push against the status quo and tell the powers that be her findings, and that’s going to cause problems. Because she’s effectively showing the Judges that their entire societal system doesn’t work and needs to change. So that was a story that had huge dramatic potential. This could change Dredd’s world.

Judge Maitland is at the center of this. She’s in a very precarious position as the story begins. Can you talk a bit about how you view her as a character and what her arc will look like, as much as you can say?

RW: You’ll have to read the story for her arc, but when “A Better World” begins, she’s been running one City Sector under her policy of spending more on education and social programs and less on Judge funding: and the numbers are in and they are working. Crime is substantially down. So now the City Council have to decide what to do next… and they give her ten Sectors to trial this next. Some people are extremely unhappy about this change. Certain Judges think it’s putting their lives on the line, taking resources from them. Some powerful people in the City see this as an agenda they can use to promote their own push for power.

But in terms of Maitland’s character – she’s driven, meticulous. That’s why Dredd trusts her in a way that he doesn’t trust many. She’s run the data and the models over and over. She KNOWS her system is a better one, both for the citizens and the Judges, so she’s going to push it, whatever trouble that brings her. She’s no do-gooding savior. She’s doing her job.

AW: She’s very, very good at what she does, but what she does isn’t making people happy. And while she’s not unaware of the politics of power, she can see herself as a little above them as she has the models and facts on her side. She can push a lot through by sheer force of will but isn’t always one to go around an immovable object instead of trying to smash through it.

One significant bit of nuance here is that the data suggests that Judge Maitland is correct and that the Judges may be doing more harm than good. How does that steer the story you are telling? Why was that an important point to make? Does the story then become more about how the udges react when presented with this information?

AW: A twist with Maitland, as opposed to other reform storylines like the Democracy ones, is that she’s not coming to this from a position of idealism, she’s actually coming to this from a position of hardcore pragmatism. The one area where she’s idealistic and her pragmatism fails is her assessment of her fellow judges. If she’s obviously right, and she’s got the numbers to back her up, she thinks they should be on her side. But judges are human, and humans don’t always act like that. They especially don’t act like that when their own position is being challenged.

RW: One of the wonderful things about Judge Dredd and why it has prospered over nearly 50 years is that the strip can sustain any kind of story from week to week – one story comedy, one story horror, action thriller, political satire. Dredd the hero one week, the villain the next.

When you’ve written Dredd for a few years as I and Arthur have, you start thinking that you have to pay your dues and occasionally remind the readers that the Judges are a totalitarian regime and that Mega-City One is a cautionary tale. That, in this post-apocalyptic world, the citizens get no vote. The Judges rule by fear and terror. As my story, “The Small House,” had one Judge openly say to Dredd: “we’re fascists.” This is one of those Judge Dredd stories.

We know what the story is about. How is the story told? Are we looking at something action-packed as things get out of hand? Or something more personal, or investigative and laden with intrigue?

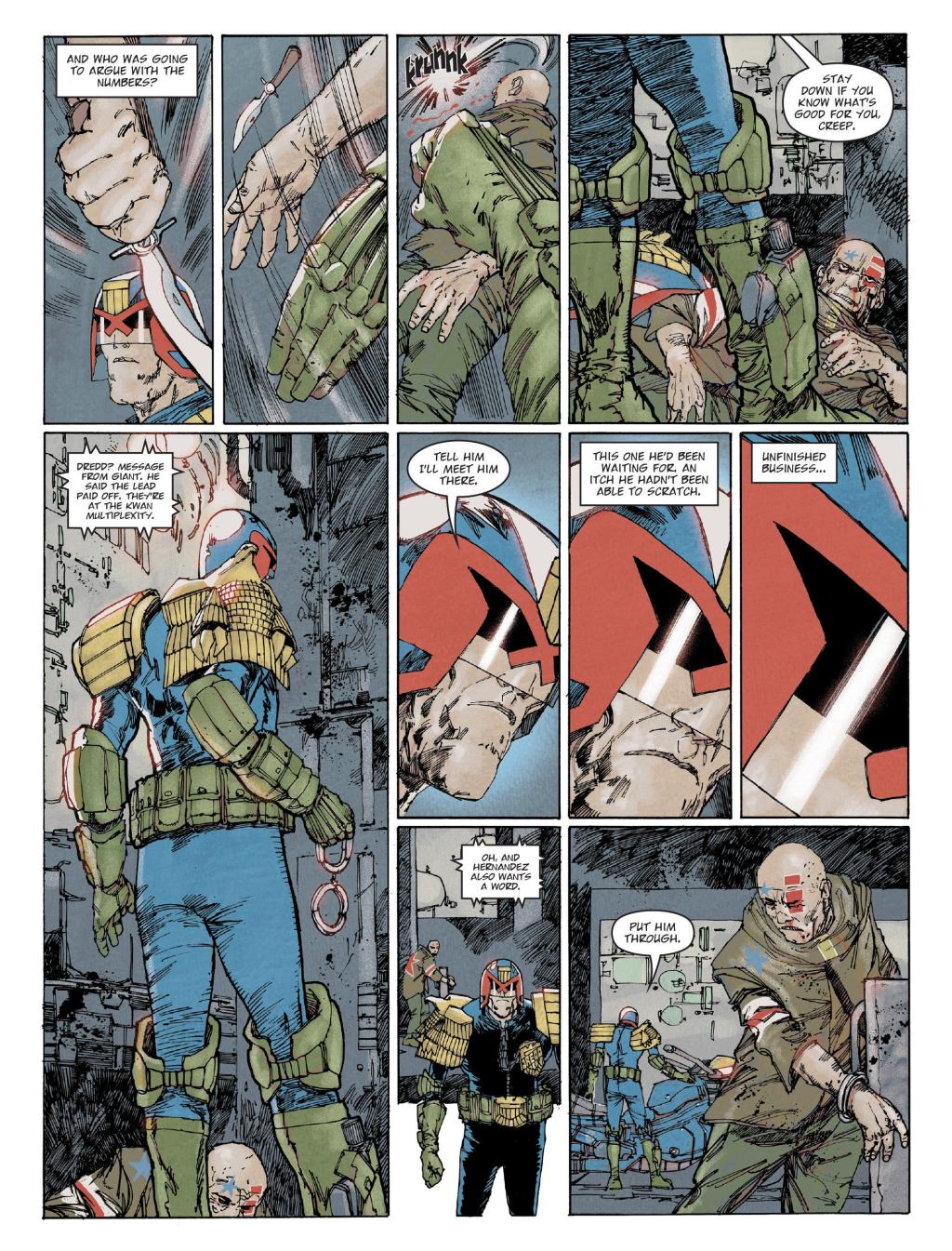

RW: There’s several plot threads interweaved in “A Better World.” There’s the political drama of whether Maitland’s experiment will work when it’s rolled out over more City Sectors. There’s certain Judges pushing back against it, so there’s a schism in the Judges there. There’s media mogul Robert Glenn who, in a Fox News/GB News style, sees an opportunity to weaponize this to promote his own business interests, consequences be damned. There’s how the City and the Citizens respond to this potential new world. Could this bring democracy, finally? And then there’s the action thread – Judge Dredd hunting down a mercenary called Major Domo who had previously been paid to assassinate Maitland. Dredd needs to be front and center and he very much is – it’s a Judge Dredd story after all.

AW: It should work well as a self-contained piece, but there’s a lot of threads running through it that follow on from the previous story’s me and Rob have worked on, which I think gives it a lot of texture and means we get to touch on all those things. I think the death of the story would be if it was just talking and theory, and it’s very much not that.

Police matters can be a real hot-button issue. Was there much talk about handling this story carefully, or have you treated it like any other Judge Dredd story you’ve worked on?

AW: Well, I lived through the years 2020 to 2021 in America with a crippling social media addiction and an inability to look away from bad shit happening… I sure have some OPINIONS on things. And thematically, Dredd is all about policing and social order and the structures of power, so it’s all grist for the mill that’s going to feed into that. If the stories didn’t say anything there wouldn’t be any point to them, and honestly, whenever real-world events have gotten uncomfortably close to what’s on the page in the past I’ve always felt bad for not going further. But it has to work as a story and fit in the setting – anything that can do that is absolutely on the table.

RW: I like to think we’ve tried to be sensitive here, but as always, your mileage may vary. It’s, hopefully, the type of story that will cause some debate. Arthur was living in a city in the US where there were major riots over this issue, so he felt it in a first-hand way. But, ultimately, this is a Judge Dredd story. Dredd has a long history of brilliantly prescient and pertinent social satire and dramatization.

Go read Mike Molcher’s I Am The Law for a detailed and very enjoyable exploration of the strip’ history in this regard and how it’s often, unfortunately, predicted what’s coming in the future. Just the way that in recent years, all across the world, democratic regimes seem to be falling to be replaced with autocratic ones, shows that Judge Dredd is as important a warning note now as it ever was.

There are often many forces pushing back against change in the real world, but there’s one such force unique to long-running stories: narrative expectations. When readers open a Judge Dredd story, they have certain assumptions about what Mega-City One will be like, and the overbearing presence of the Judges is chief among them. How have those expectations and how much you can realistically alter Dredd’s status quo affected your approach to this story?

RW: The trick with any long-running narrative world is to push against the supporting structures of what makes the story work and sustain but not to break it and why people love it. You’re constantly fighting with the fact that these stories need to have dramatic stakes and consequences, but also, you’re operating in a shared universe where other writers tell their stories. It’s a bit of a highwire act. But if you read Dredd through the story’s history, there are major changes to the world at times.

Chaos Day killed around 43 million of Mega-City One’s Citizens (if I recall correctly), and in many pivotal ways, the Judges have been struggling ever since. Things do change in Dredd’s world. Dredd changes – glacially – but when he does it’s a big deal. Dredd backed Maitland’s experiment with the Judge’s Council in “The Pitch.” That was huge. To hear him admit in his stoic way that maybe things have to change.

AW: The city becoming a utopia just like that may be a long shot – but the Dredd universe is a long-running and continuous one with a lot of threads running through it. Just like this story is the culmination of a lot of threads that started with Carry The Nine, I think there’s going to be a lot of threads that come out of it and lead to other things. And a status quo always seems immovable until it isn’t.

And then, of course, there’s Dredd. What can you say about his role in this moment for the Judges?

RW: Dredd’s no great thinker. He’s The Law, force of will, gut instinct, and the boot and the fist of this regime. But he’s not stupid, either. It’s war on the streets every single day. He’s lost countless colleagues over the years. And he’s aging, getting ground down by it all as anyone does in a life of longevity. I think he knows something needs to change, maybe, but he doesn’t know the consequences. That’s for others to work out.

AW: I can see it meaning different things for the Judges and for Dredd. By the time the story is up, I could see some trajectories getting changed…

Finally, there’s the visuals. I’ve read the first chapter, and it’s stunning, which is not a surprise. Did you approach the visuals for this story any differently than any past Dredd story? Did it involve a lot of collaborative discussions, or did Henry Flint work more independently once given the script?

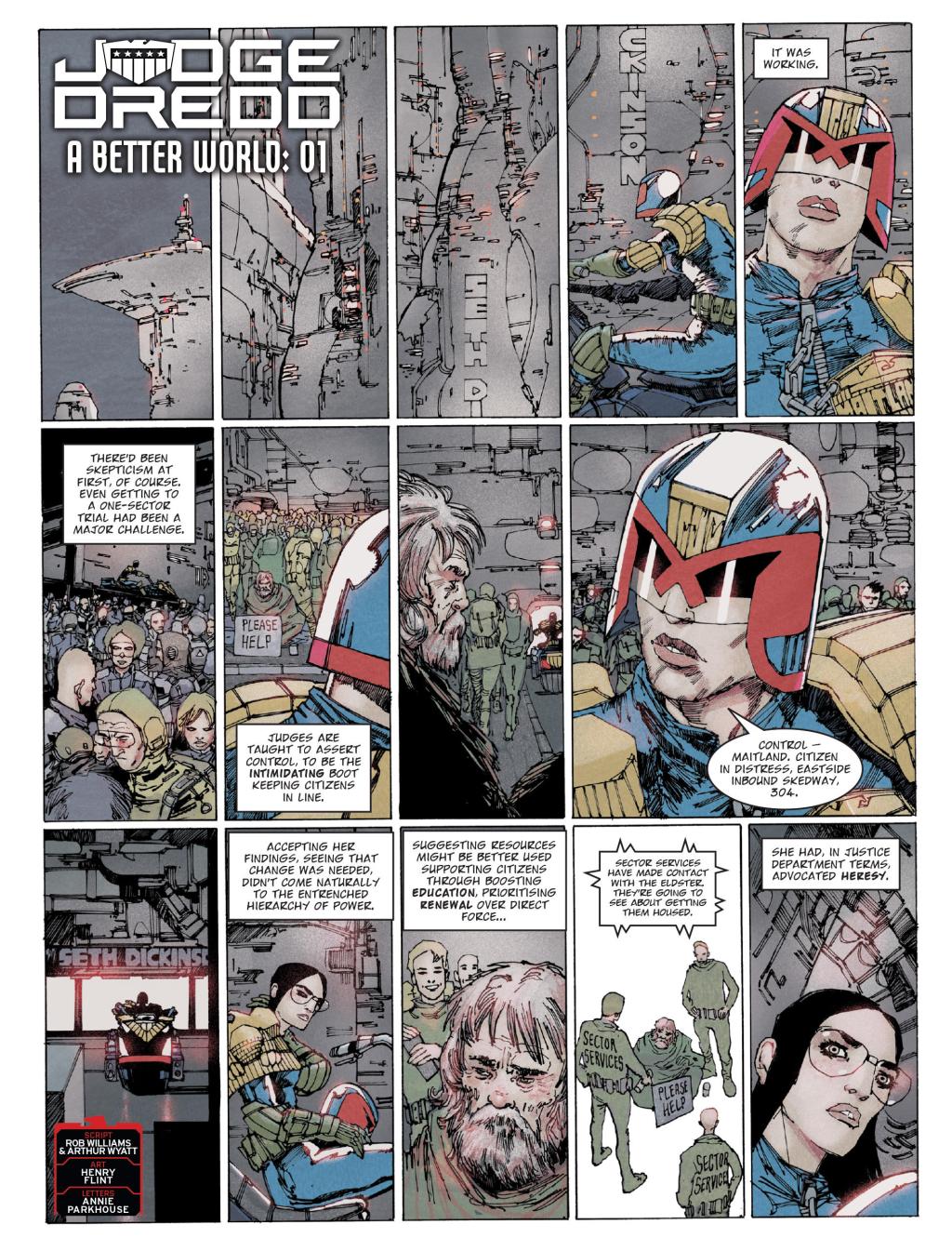

AW: Henry Flint did amazing things with the script. Entirely of his own volition, I should add. Nobody said to him, “Hey, you should make your job harder by putting everything on a 15-panel grid,” he just upped and did that of his own accord. So every page you see started as a script for a more conventional 5-7 panel page, then he split that up and reworked that, and provided a lettering guide for how the panels and speech would be split up amongst them. We really are the beneficiary of Henry putting in a lot of extra work there, and it works amazingly.

RW: Well, first off, I genuinely think Henry Flint is one of the best artists and storytellers we have in comics, and it’s sort of criminal that only 2000 AD readers seem to know that because his US market work has been relatively limited. I’ve collaborated with Henry on a bunch of stories over the years – most notably on Judge Dredd stories like Titan and The Small House (go buy them in GN). But on this one, Henry asked us if we minded if he “tried something different.”

His instincts are always so good we said “sure.” So he’s taken scripts that are often 5/6 panels and broken each page down into character and visual beats that are sometimes 12/13/14/15 panels. It’s pretty dizzying how he combines the chaos and immense detail of Mega-City One with these incremental small beats that are pure comics. And he’s colored himself. It’s a hugely ambitious undertaking and looks like something unique in the 47-year history of 2000 AD.

It’s an extraordinary-looking comic.

2000 AD Prog 2364, featuring the first chapter of “A Better World,’ goes on sale on January 10th. If you’re new to 2000 AD, try checking out the recent 2000 AD jumping-on issue, comprised entirely of the first chapters of new stories, or the Best of 2000 AD anthology series.