It’s 2024, and as of the last fully vetted numbers available to us, about half of all new physical media sales come from DVD. The format, which has been in wide commercial circulation for more than 25 years, is close to eclipsing VHS as the longest-running home media format in commercial use even as big-box retailers like Best Buy have stopped carrying physical media altogether (and Target is pulling back). Still, with not only Blu-ray (now about 18 years old) but also 4K UHD (eight years) available in stores and online, why is it that so many consumers are still buying DVD? The answer is both simple, and mutlifaceted.

Videos by ComicBook.com

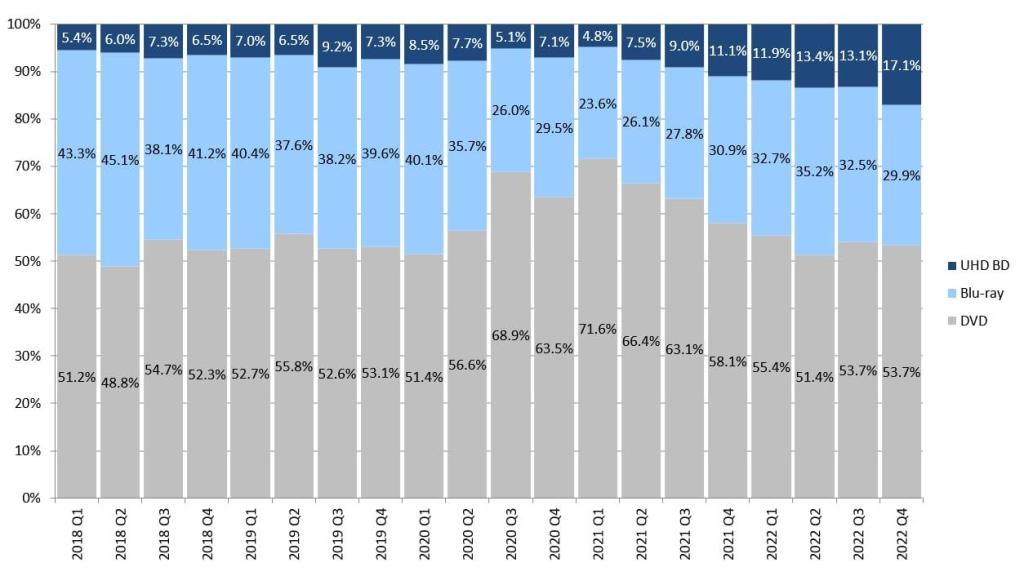

According to industry numbers, even in the Blu-ray era, there has hardly ever been a fiscal quarter where DVD wasn’t the biggest seller on the disc market. The format routinely accounts for 50% or more of disc sales, with Blu-ray and 4K splitting the rest. Those numbers, compiled by Yoeri Geutskens for his Ultra HD Blu-ray account on Twitter, are particularly interesting because they seem to illustrate that Blu-ray is losing as much (sometimes more) market share to 4K as is DVD. The numbers also end at the end of 2022, and if 2022’s trends held through 2023, it suggests that DVD is likely below 50% of the market now, and 4K could represent as much as 20%.

You can see Geutskens’s chart below.

So, let’s dig down into this a little bit.

Historically, Hollywood’s relationship with physical media has always been a bit fraught. Studios filed a historic lawsuit that sought to keep VHS and Betamax recorders off the market in the U.S. when the technology was first developed in the 1970s. They lost that case, and the ability to record TV programming changed the way audiences engaged with entertainment and pop culture forever.

In the 1970s and 1980s, first video clubs (which required a paid membership and often involved shipping tapes around the country) and then video rental stores popularized the idea of sharing, since pre-recorded tapes were wildly expensive. By the time Top Gun came to home video in 1987, demand was so high that Paramount decided to make the blockbuster available for $20 — a huge discount relative to what commercial VHS tapes had previously cost. The sale were enormous, and a home video sales market emerged shortly thereafter.

By the ’90s and 2000s, sales of VHS and later DVD had become such an enormous part of the Hollywood ecosphere. This coincided with the dawn of the ’90s indie film movement, and allowed strange, niche movies that were made on the cheap to become cultural touchstones. Reservoir Dogs, Clerks, and Dazed and Confused are among the many movies that became instant classics despite comparably modest box office performance.

“The DVD was a huge part of our business — of our revenue stream, and technology has just made that obsolete,” Matt Damon told Hot Ones in 2022. “And so the movies that we used to make, you could afford to not make all of your money when it played in the theater, because you knew you had the DVD coming behind the release, and six months later, you’d get a whole other chunk. It would be like re-opening the movie, almost. When that went away, that changed the kind of movies that we could make.”

Almost exactly a year ago, DVD & Blu-ray Release Report counted an estimated 294,000 movies officially released on the DVD format. That compares to roughly 39,000 on Blu-ray and 1,300 on 4K. Those numbers have likely shifted a bit — and that same site reportedly earlier this year that 2024 was actually the most prolific year ever for number of disc releases — but the proportions remain more or less the same. There are a few reasons for that.

First, let’s talk about availability.

Every generation of home media has had its own batch of totally unique titles. A not-insignificant percentage of commercially released VHS and Beta tapes never came to DVD, and (as you can see), a huge number of DVD releases never got HD physical releases. Obviously, there are plenty of movies on disc that never got wide digital release, and there are a number of streaming-only titles that haven’t got physical copies you can buy.

(Incidentally, there were even a few titles released to RCA’s short-lived CED format, which didn’t make their way to VHS after the format died in the mid ’80s. This isn’t new.)

Rights issues are frequent complicating factors on older TV shows and movies, especially. Whether it’s distribution rights, royalty deals, or music rights, older contracts often didn’t account for home video. This is particularly true of TV, since it was difficult to get more than two or three hours on high-quality VHS recordings. That means most TV shows, which often had 20+ episodes per season, never got VHS releases. When they did, it was often just compilations of two to four popular episodes.

Hugely popular shows like M*A*S*H, Star Trek, and Cheers would get multi-tape, expensive Time-Life or Columbia House releases. But those were small runs, offered through subscription clubs, and far from the norm. Except for Cheers, where it was the “NORM!”

In any case, it wasn’t until the advent of DVD in 1996 that full seasons of TV started to get mainstream home media releases. A lot of shows made prior to that didn’t take a rights and royalties structure for home video into consideration.

DVD became an ideal format once it was widely available. Not only did a DVD hold a lot more data, in better quality, than a VHS tape, but the discs were a lot more compact, especially if you wanted to carry more than one or two with you between locations. Digital has eliminated the need to carry anything at all — but discs are still selling. Part of that is probably the availability of titles on DVD that aren’t available elsewhere.

Another reason DVDs are still being produced and sold is, counterintuitively, the end of physical media rental culture. Now, many consumers have no choice but to buy a movie if they want to see it at all.

Until fairly recently, it was possible to ditch your discs for digital, and still be able to count on having a video store fairly nearby if you wanted to see a movie that wasn’t streaming. The end of chain video stores has made DVD rentals (and cheap sales of pre-viewed movies) more difficult and more rare. Even Redbox, the current largest rental chain in the U.S., has a pretty limited back catalog of physical disc titles, due to the nature of their locations (which are sophisticated vending machines rather than stand-alone stores).

The sales numbers for DVDs in 2023 are not yet available, but home entertainment sales went up in 2022, and it would not be surprising if they went up again last year. When Family Video finally shut down in 2020, they left at least one major player in the physical media rental market: Netflix’s own DVD.com. But that site finally closed last year, effectively ending access to convenient disc rentals for most Americans. While alternatives exist, nobody has the scale or built-in customer base that allowed Netflix to have both a broad library and low prices.

All of these factors suggest people who want hard-to-find movies are going to have to buy their own DVDs. And again, yes…DVDs. Because almost every title that’s available on disc, but not digital, is only on DVD. There are exceptions to that rule, but not many, since the advent of Blu-ray coincided with the start of the streaming era, and so most discs available in HD also nailed down some kind of digital distribution deal at the time.

Now, the cost.

Okay, so availability is a pretty good reason for consumers to buy discs — DVD, Blu-ray, and 4K — even in the streaming era. But why haven’t we moved on from DVD, specifically?

Two things: convenience and cost.

In terms of convenience: studies indicate that around 80% of U.S. households still have access to a DVD player. In addition to traditional DVD players, nearly all optical drives in computers and video game consoles also support DVD. Blu-ray compatible optical drives are less common, with around 67% having access to a Blu-ray drive. These are older numbers, from about five years ago. It seems likely, given what we know about media sales numbers, that even if overall ownership of players has declined, the proportions are pretty similar.

That means, in addition to a wider array of titles available on DVD, there is a larger number of consumers who have easy access to a DVD player. There’s also a 100% penetration of DVD access in households with a Blu-ray player, since Blu-ray and 4K players are all backwards-compatible to DVD, while DVD players aren’t able to play higher resolution discs.

Integration into computers and game consoles is something that separates DVD from VHS. 15 years after the last tapes rolled off the assembly line, it has become increasingly difficult to find a decent VCR for cheap. Optical drives, on the other hand, will likely be cheap and easy to find for the next 30 years. There are just so, so many of them out there. And unlike VCRs, they can be easily and inexpensively bought and sold on marketplaces like eBay that require shipping.

Consumers buying new players in the 2020s are unlikely to be buying DVD unless they have a specific reason, since Blu-ray players are not significantly more expensive. Still, the discs themselves aren’t as inexpensive as DVDs…and if you go up to 4K, there’s a supply and demand issue that impacts pricing.

We couldn’t find accurate numbers that indicate how many consumers have access to a 4K player, but given the fairly limited number of titles available on the format, it’s likely fewer people have felt pressured to upgrade from Blu-ray to 4K, than from DVD to Blu-ray. And while Blu-ray players cost just a hair more than DVD for entry-level units, the same isn’t true for 4K players, which routinely cost three to five times as much as a comparable DVD player.

It’s likely some of this is about the higher-end tech — 4K players are obviously more sophisticated in terms of their capability, and we have all heard about component shortages impacting virtually every segment of tech since 2020. Some of the price difference, though, is likely about supply and demand. The 4K market has never grown as big as Blu-ray, and the rise of streaming and decline of overall physical media sales — physical media accounts for only about 5% of all physical media sales in 2022 — has reduced overall demand for disc readers.

Lower overall demand means less mass production, which means any given unit is more expensive to produce. Therefore, it will be more expensive to buy. That has kept the price of 4K players from sinking to the bargain basement levels of DVD and Blu-ray players, and if you don’t have a player…well, most people aren’t pre-buying their 4K discs “just in case.” And while many Blu-rays come with a complementary DVD in the box, 4K comes with an extra Blu-ray instead. If you have a Blu-ray but not a 4K player, you can get a Blu-ray and an extra DVD for (usually) about $5 less than getting the 4K version and waiting it out.

There’s also the quality issue.

If you worked at a video store in the 2000s, you had a lot of conversations with customers about the quality difference between DVD and VHS, and later, the difference between Blu-ray and DVD.

In my experience, most casual movie fans could easily see the difference in quality between VHS and DVD. Far fewer could tell the difference between DVD and Blu-ray with their naked eye. Granted, 4K TVs weren’t yet common, and the average TV was smaller back then, but it seems likely that even fewer casual consumers still can tell the difference in quality between Blu-ray and 4K UHD.

Think of all those people who still use motion smoothing on their TVs, oblivious to the quality difference they’re missing out on. That’s the kind of person we’re talking about here, not the alpha consumer with an expensive rig. For those people, DVD is probably good enough.

That’s compounded by the fact that, for many, it’s uncommon to break out a disc at all. On top of all that, streaming services are often sending a signal by default that’s more comparable to DVD quality than Blu-ray or 4K. No matter how big or good your TV is, a lot of consumers simply don’t feel like they’re missing out by watching a DVD-quality version.

What’s next for DVD?

So — there are a lot more movies and TV shows to choose from on DVD than any other disc format. They’re less expensive, and the quality of the viewing experience is roughly comparable to what you get from streaming — the way most consumers are engaging with most content anyway. All of this adds up to DVD accounting for far more disc sales than its higher-quality, higher-cost competitors.

VHS still exists, in a very small way, as a niche, nostalgic thing, both with cult distributors like Lunchmeat Video and Witter Entertainment. DVD, on the other hand, maintains a significant presence in the physical market. It doesn’t hurt that Walmart — the biggest brick-and-mortar seller of home video — is still stocking more DVDs than they are Blu-rays and 4K discs. They have also expressed an interest in buying Studio Distribution Services, the largest distributor of physical media discs, which is jointly owned by Hollywood giants Warner Bros. Discovery and NBCUniversal.

With far more titles, and far more sales, is there really any question why DVD still exists?

VHS tapes were in mass production from 1976 until 2006. Will DVD make it to 30 years old, and steal the title of longest-running commercial home media format?

As of right now, it looks like it. While DVD sales have shrunk significantly since their peak in 2005 (when they raked in $16.3 billion), major studios aren’t currently in a position to leave $1 billion a year on the table.