In keeping with the theme of ’90s nostalgia, though, the column immediately fell wildly and hilariously behind.

Videos by ComicBook.com

That said, we’re back, and starting Wednesday, we’ll be biweekly.

Our previous installment gave a list of ten things I loved about the ’90s and, because this topic is one near and dear to my heart, I’m starting with what I called at that time “momentum.”

There are two halves of the same whole that gave a sense that comics in the ’90s had a sense of momentum: It always felt like something was happening…and it always seemed to be building and building.

Some will argue that such an emphasis on plot happened at the price of sacrificing character, that spectacle overwhelmed quality and that the feeling of something always happening is what gave us the event-driven culture that frustrates many fans and critics today. There are kernels of truth in that, but ultimately, the feel of the average comic in the 1990s is wildly different than today’s — and in many cases, far more entertaining.

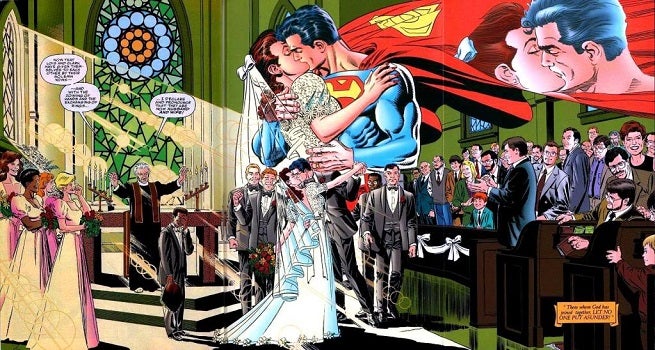

The fact that there was so much forward momentum also propelled stories forward. Characters aged, died, married, had kids, were replaced. These things not only don’t happen anymore, but in many cases the ones that already happened have since been actively retconned out or magicked away to restore a pre-1985 status quo.

It wasn’t until the late ’90s or so that the phrase “writing for the trade” began to be popularized. That’s in part because the trade paperback market was next to nil at the time; Watchmen, Maus and The Dark Knight Returns all sold solid numbers, but in terms of collecting the month-to-month stories in your regular series? That basically never happened. The Death of Superman was an early exception to that rule, but not the first. Stories like A Lonely Place of Dying, The Judas Contract, The Deaths of the Stacys and more had been in collected editions that sold pretty well before then.

Still, those stories were likely not written with trade paperback concerns playing in the backs of the heads of writers and artists. And certainly it hadn’t started to decompress the storytelling yet. If anything, many ’90s comics aimed to do too much in an issue and ended up cluttered and potentially confusing.

Back when the serialized magazine format was the primary way for most people to read — or even just for the desired audience to read — those singles were far more packed with story. There’s lots of talk now about how binge-watching has changed TV forever, but comics beat them there by a bit. Comic book fans started “binge watching” in the late ’90s as the market for collected editions emerged in earnest and for many, this writer included, that’s been the primary choice for reading ever since.

That’s yielded a lot of consequences, not all of which are intentional. While writing for the trade allowed writers to take a bigger picture approach to comics scripting, ultimately resulting in a lot of stories being deeper and more complex, comics also lost their sense of urgency. During that time, you could see a steady increase in phrases like “This six-issue story could have been finished in two” on the part of critics who examined comic books.

The end result of this is that for people who want high-octane adventure that’s easy to get a casual fan of the movies, or a non-fan altogether, into, your best bet might be to go back to 1997 or earlier.

There are plenty of people who didn’t like this kind of evolution; when Superman got married, there were detractors (heck, there were plenty of detractors just of the Man of Steel reboot itself) and there were organized groups dedicated to opposing replacement/legacy heroes like Kyle Rayner and Connor Hawke. And a lot of the ongoing stories weren’t that good. Still, there’s something attractive about the notion of ongoing, serialized stories being…well, ongoing. Especially when the universe pretends to be. The New 52 is, in many ways, less disruptive and more honest than something like Green Lantern: Rebirth, which tried to reset the clock back to 1990 without admitting that was its goal.

Marvel has become the worst offender in that regard; since Marvel NOW!, they’ve been soft-relaunching every 18 months or so, telling one massive story across the whole publishing line, and then soft-relaunching again. There’s value to that kind of storytelling and obvious advantages to it…but I miss a point of view where the stories told before mattered, and retcons had to be somehow justified.

Probably the beginning of the Green Lantern: Rebirth style of “Because we said so” retcon was Garth Ennis’ The Punisher, where the title character famously dismisses the “undead avenger” era of the book with three sentences. That era was short, widely panned and didn’t seem to fit with the character, while his dismissive, cutting dark humor does fit, so most people never really said anything.

In any event, I’m not saying that this is the better way to tell stories, but it’s a legitimate way to tell them, one that many fans enjoyed, and one that’s basically entirely gone in the era of everything being driven by vast, interconnected events that have to feed into the next movie.

Comics have always featured the dead returning to life, old status quos being re-established and a general sense of what Stan Lee called “the appearance of change.” But for a short period of time, that was relegated to being the exception rather than the rule, and operating with new rules in the old, beloved universes was fun and inspired a ton of creativity.

Where the constant sense that something big was underway now tends to subvert the stories being told and stunt character growth by taking page count away from the main story and giving it over to “the universe,” 20 years ago we had a culture where the writers were expected to juggle both.