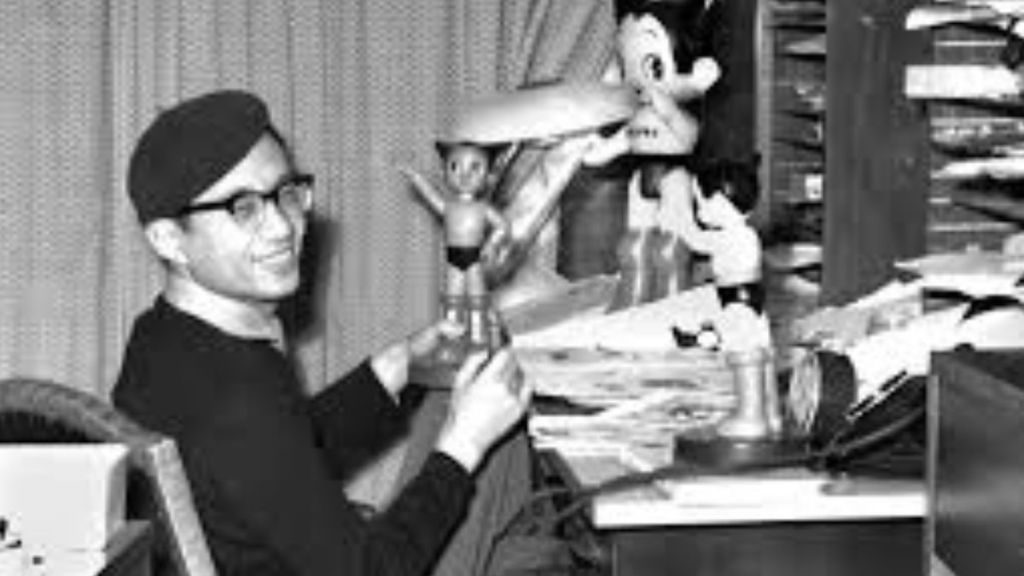

Thirty seven years ago today, the anime industry lost a figure whose influence still shapes what viewers see on screens around the world. On Feb 9, 1989, Osamu Tezuka died at 60. It is easy to treat him as a myth because the scale of his impact feels too large for one career. He is commonly called the God of Manga, but that nickname can flatten the real story.

Videos by ComicBook.com

He changed how manga was paced and framed, then helped create the industrial conditions for television anime to exist at scale. Modern anime is not simply inspired by Tezuka. It is built on choices he made, some brilliant and some controversial, that became standards.

The Man Behind The Legend

Tezuka was born in 1928 and came of age during and after wartime Japan, a period that shaped the moral questions that run through much of his work. He trained in medicine and earned a medical degree He could think scientifically and emotionally at the same time. That combination shows up in stories that blend wonder with anatomy, ethics, and mortality. Even when his worlds are whimsical, the stakes often come back to the value of life and the consequences of power.

Yet the deeper point is not volume. It is range and intent. Tezuka treated comics as cinema on paper. He borrowed from film language, especially the feeling of camera movement and montage. He pushed longer story arcs and more complex emotional beats at a time when much popular manga was still closer to short gags or simple adventure rhythms. If manga could be modern literature for the mass audience, Tezuka helped prove it.

How Tezuka rewired manga storytelling

Tezuka is often credited with popularizing a cinematic approach to paneling, including dynamic angles, rapid cuts, and decompressed moments that linger on emotion. These techniques now feel natural in manga and in anime storyboards. At the time, they were part of a broader argument that comics could deliver the same dramatic grammar as film.

Works like Jungle Taitei known in English as Kimba the White Lion and Ribon no Kishi known as Princess Knight helped establish genre templates. Princess Knight in particular is frequently cited as foundational for shoujo and for stories that play with gender roles and identity. Tezuka did not invent every element he used, but he had a rare ability to synthesize influences into a form that others could adopt.

Mushi Production and the birth of TV anime economics

Tezuka founded Mushi Production in 1961, and it became one of the first major anime studios. This is where admiration for Tezuka needs to be honest. His creative ambition was enormous, but he also helped establish a production model that anime has been struggling with ever since.

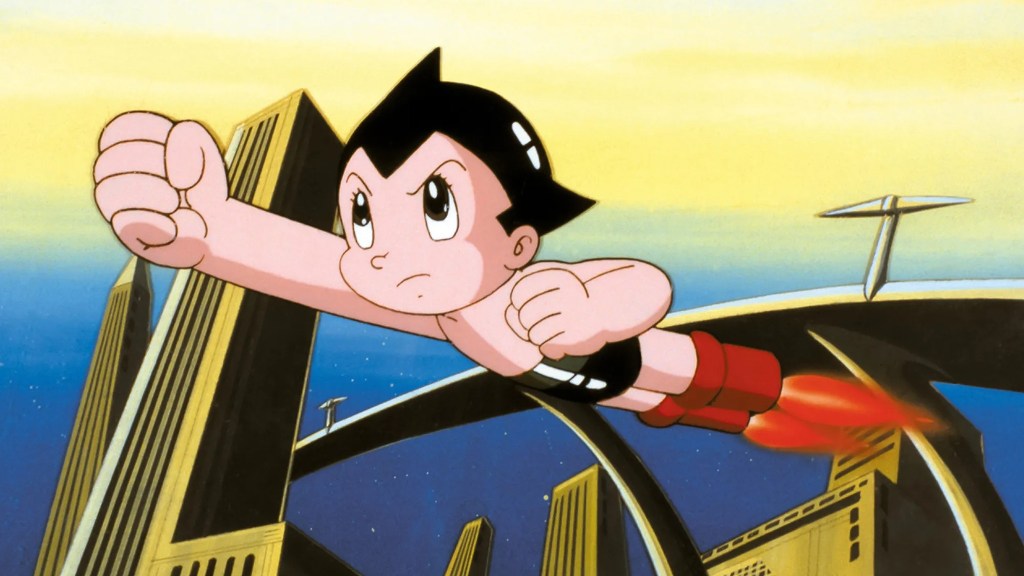

In 1963, Mushi produced Tetsuwan Atomu (Astro Boy), widely recognized as the first successful Japanese television anime series. It was not the first animated work made for TV in Japan, but it was the breakout that proved a weekly anime series could capture a mass audience and build a merchandising ecosystem. Tezuka reportedly underpriced episodes to get the series on air, essentially trading profit for distribution and cultural presence. That gamble worked for Astro Boy. It also normalized tight budgets and punishing schedules.

The industry term that followed was limited animation, which uses fewer drawings and emphasizes strong layouts, held poses, and smart reuse of cycles. The irony is that what many people celebrate as the anime look was partly shaped by constraints. Tezuka made those constraints into style, and the industry adopted the style as necessity.

Themes that still define anime

Tezuka’s work returns again and again to humanism. He was fascinated by how societies justify violence and how individuals resist it. In later works like Black Jack, he explored medical ethics through a rogue surgeon, blending procedural storytelling with moral ambiguity. In Phoenix, he attempted something even bigger, a sprawling meditation on death, rebirth, and the cost of immortality. These projects are statements of purpose, and they helped expand what manga and anime audiences expected from popular storytelling.

Another lasting contribution is his balance of tonal shifts. Tezuka could move from slapstick to tragedy without losing sincerity. That tonal agility is now a familiar feature in many anime series, where comedy can sit next to existential dread. It is not always done well by later creators, but Tezuka showed it could be done with empathy.

Calling Tezuka the greatest legend is a recognition that he helped create the foundation and the blueprint. Yet foundations have cracks. The production practices that made weekly TV anime viable also contributed to decades of underpaid labor and chronic overwork. Tezuka’s choices were shaped by his era and by a desire to get animation into homes. The cost of that decision is still being negotiated by studios and artists now.

What do you think? Leave a comment below and join the conversation now in the ComicBook Forum!