Anime fans were shocked and excited when Sunrise announced it was producing the next Gundam series in collaboration with Studio Khara. The collaboration compromises anime veterans who have worked on Neon Genesis Evangelion, including series figurehead Hideaki Anno. Fans were ecstatic about the announcement, hoping that Anno and the rest could bring in the same deconstruction nature that made Evangelion a massive hit in the first place. Fans want the next Gundam to be depressive, subversive, and a thorough insight into a single creator’s bleak vision.

Videos by ComicBook.com

However, fans seem to forget that Gundam has always been that since its inception. Gundam has always dealt with the psychological toll its protagonist suffers while piloting the mechas and the ethics of having children be part of the army. Before fans were meme-ing for Shinji to get in the robot in Evangelion, Amuro had to be slapped back into the Gundam in the original Mobile Suit Gundam show. Both the Gundam franchise and Evangelion have been a deconstruction of the mecha genre, destroying the power fantasy of owning a giant robot and covering the mental hardship of piloting a weapon of mass destruction. Evangelion is more abstract, whereas Gundam’s themes revolve more on the overall message of “war is bad.” Yet neither franchise is as different as anime fans seem to believe, forgetting how much the original Gundam shows influenced Evangelion itself.

[RELATED: Is McDonald’s x Evangelion the Next Fast Food Collab?]

Gundam Deconstructed The Mecha Genre Long Before Neon Genesis Evangelion

There’s an argument that Evangelion isn’t really a mecha series, as the machines the characters pilot are not technically fully mechanical. The show is also more concerned with how piloting the Evas affect the characters rather than the machines themselves. Nonetheless, the show plays within the tropes and themes of a mecha, subverting people’s expectations of what a giant robot series could be.

Gundam is often viewed as a traditional mecha series because of how ubiquitous the franchise has become globally. When people think of giant robots, they think of Gundam as the trope, whereas Evangelion is the subversion of the trope. However, both series serve as commentaries of the giant robot genre, critiquing and analyzing the psychology of piloting robots. The Gundam franchise has always stuck with a grounded reality, with Gundam creator Yoshiyuki Tomino speaking about how the idea of the original series was inspired by Japan using child soldiers in the Pacific Wars.

Classic mecha series that predated the original 1979 Mobile Suit Gundam show, like Mazinger and Gigantor, were built around the fantasy of owning and piloting a giant machine as a child. These iconic giant robot anime focused on the fun aspect of using a robot, something that all children have fantasized about. Tomino wrote and directed Gundam ’79 to be the opposite, hammering the idea that it wouldn’t and shouldn’t be fun piloting a giant weapon. The original series is cited as ushering in the Real Robot subgenre, a more grounded look at giant robots.

The Protagonists in Gundam and Evangelion Were Always Meant to be Atypical

Amuro Ray was the only one capable of piloting the Gundam in the original series, leaving the burden of responsibility on his shoulders. He was also only sixteen years old, and unlike previous mecha protagonists, he acted like a teenager. He would often be overwhelmed with piloting the Gundam and disobey orders. He constantly complains about piloting and would have to be coached into heading back into the field.

This is similar to what Evangelion does with Shinji during the series. Shinji was thrust into the role of an Eva pilot by his father, and the series covers his slow mental collapse as he continues getting into the robot. Both Shinji and Amuro are used and abused by the grown-ups in their lives, examining the ethics of having children fight in war. While Evangelion is more concerned with dealing with the psychological ramifications of kids piloting giant weapons, Gundam is more of a direct criticism of war and how people aren’t viewed as individuals within the military.

Tomino would review the same themes about child soldiers with future Gundam shows like Zeta and Victory. Mobile Suit Zeta Gundam is even more bleak, touching on Tomino’s growing nihilism against war. The final episodes of Zeta are some of the most infamous within the mecha genre, ending with the deaths of nearly the entire cast and the complete mental breakdown of the main character. The influence of Zeta’s ending can be felt in future mecha shows, including Evangelion. The End of Evangelion film has all of humanity dissolved into primordial fluid to become one single consciousness. The original movie and series ends on a dark note, similar to Zeta, where hardly anyone is left standing.

The Difference Between Gundam and Evangelion Isn’t Subtle

One difference between classic Gundam and Evangelion is that the latter is more abstract and obtuse. Evangelion intentionally confuses audiences with odd dialogue and surreal imagery that makes you question the scene’s authenticity. Even though Gundam is almost always direct and literal, Gundam’s creator has played around with a more surreal tone with Space Runaway Ideon. Tomino directed Ideon to be less literal and has an even bleaker ending than Zeta Gundam. Fans have connected several elements from Ideon with Evangelion, specifically the biblical allegorical finale of both series.

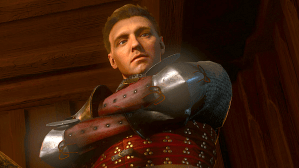

But when it comes to Gundam itself, the biggest difference stems from when the creators’ grew up. Tomino grew up in post-World War II Japan and saw war as nothing more than unnecessary evil. Tomino’s work was more concerned with what compels humans to go to war and the political corruption rooted in society that leads to conflict. Anno grew up in the Cold War, living in constant anxiety that humanity was on the brink of collapse. Evangelion is set in a world ravaged by cataclysmic events, centering on humanity learning to pick up the pieces and how it affects the newer generation. Gundam GQuuuuuuX will similarly take place in a post-war society, albeit this time, the protagonist appears to be in peaceful times.

Both franchises aim to deconstruct the giant robot genre and cover deeper topics about humanity. While the idea of having a giant robot sounds cool on paper, Tomino and Anno were more interested in what that would do to a person. It is undeniably exciting to see Anno and his crew working on the next Gundam show, but the franchise was never in desperate need of an Evangelion-style make-over. The franchise has always been about how people, especially children, should never get into the robot.