It’s hard to convey to modern players who have instant access to a ceaseless supply of spoilers how revelatory playing as Raiden was in Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty. Series protagonist Solid Snake was a tease only meant for the prologue, demo, and advertising, creating a facade for new and unfamiliar players that he’d reprise his role as the star of MGS2. There was no reason to suspect he’d be usurped by a blonde no-name with an unmistakably 2000s-era haircut and play a mentor for most of Konami’s PS2 stunner.

Videos by ComicBook.com

It’s one of the most — if not the most — famous bait-and-switches in gaming history and is the most pointed example of Hideo Kojima’s penchant for switching things up in sequels. But that’s not the case for Death Stranding 2: On the Beach. Instead of reinterpreting the formula, it’s a more iterative follow-up that builds directly on the 2019 series debut; there are no explosive twists or shake-ups. It’s a bit of a letdown in that way, but it’s a complicated part of a complicated game.

RELATED: Death Stranding 2 Review: A Powerful Odyssey

The biggest games led by Kojima have made their names based on being so different from one another, and this is most clearly seen in the Metal Gear franchise. The original Metal Gear Solid gave a new vantage point to the previously 2D series, complete with voice acting and a more complex narrative. Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater took the franchise to the 1960s, starred Naked Snake, doubled down on survival-based gameplay, and took place mostly in the jungle. Metal Gear Solid 4: Guns of the Patriots aged up Snake, completely modernized the control scheme, and was the first in the series to have accurate lip synching. Metal Gear Solid V: Ground Zeroes and The Phantom Pain had modular missions that further emphasized player choice and were set in a more open world with, in the latter’s case, yet another new hero.

None of these games can be accused of resting on their laurels, and part of this explains why there’s not one near-unanimous “best” Metal Gear game. Many love MGS3 the most for its relatively simple and well-constructed narrative and some prefer MGS2’s absurdity, while others give more weight to MGSV’s smooth controls and liberating mission design. There’s a thematic consistency between each entry — be it stealth gameplay or the heinousness of war — but those pillars always supported a unique experience each time.

The individuality between entries was one of the key aspects of Metal Gear’s success, but Death Stranding 2 can’t claim to have that same core tenet. Players still control Sam Porter Bridges the whole time and waddle over desolate terrain from hideout to hideout, packing a backpack full of assorted goods as they attempt to bring everyone into the Chiral Network.

There’s a whole host of gadgets that make each trek a little easier, and a few of them are new and welcome, but many are carryovers from the last game. Being so familiar and having so many tools ends up sanding away a layer of the appealing abrasiveness of the original, though. The dense yet elegantly crafted HUD has been streamlined, but it — along with the sound effects — has mostly been carried directly over. There’s more of a focus on combat, but it hasn’t been tweaked to the point of completely overcoming the clunky gunplay of the original. Death Stranding 2 is a bit sharper than the original, but, from a visual and conceptual standpoint, is almost indistinguishable from that first game.

Death Stranding 2 offers a different bargain and seems to betray the long-standing and unspoken promise in Kojima-led games of subverting the player’s expectations in one way or another. A conservative sequel like Death Stranding 2 loses out on that experience and subsequently lacks that specific special spark that Kojima’s team’s games have almost always had. Even the “We should not have connected” tagline that implied a radical shift was buried in the game is woefully underexplored and only seems to be a buzzy marketing term left over from Kojima’s bold and awfully intriguing first idea for this successor. The scene in the game’s final moments before the credits teases another unexpected road this sequel could have gone down, however, is seemingly reserved for just setting up a future video game or film.

Settling for iteration is similar to how many modern follow-ups go. God of War Ragnarok, Horizon Forbidden West, Star Wars Jedi: Survivor, and Assassin’s Creed Shadows are just a sampling of recent big sequels that follow directly in the footsteps of their predecessors and opt to build on what was already there. Most offer upgrades yet play within the boundaries of what is expected, a testament to how risk-averse most publishers are and how many teams aren’t given second chances to offer such vast improvements.

Sequels have always done this, but it’s gotten more pronounced over the years and it’s hard not to look at the technology as a contributing factor. And this is once again easy to see in the Metal Gear Solid franchise. Kojima told Game Informer in 2005 that the “Solid” part of the title means 3D because the PS1 was the first big console that was powerful enough to realize that third dimension, and it didn’t stop there. The system’s CD format also allowed for voice acting and let MGS1 have a more cinematic story.

The PS2’s better processing meant MGS2 (and MGS3 later on) could have a more interactive environment. The PS3’s Blu-ray player gave MGS4 the ability to have longer cutscenes and bigger worlds (although Kojima had to be Kojima and say Blu-ray discs were also too small). The gulf of visual quality between generations was vast and unmistakable; Old Snake in MGS4 had almost three times the polygons when compared to MGS3’s Naked Snake model and the difference was obvious to anyone with eyes. Old Snake’s mustache alone had about the same amount of polygons as a whole enemy soldier in MGS3.

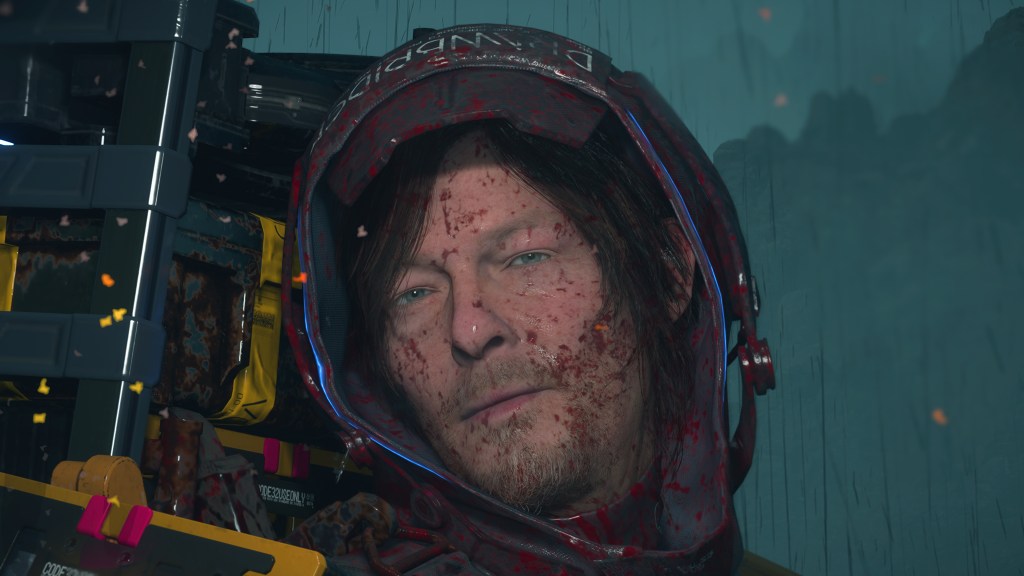

Death Stranding and its follow-up don’t have nearly as big of a polygonal disparity. The difference between Sam’s models in both games is definitely noticeable but isn’t as great as that seen in the Metal Gear Solid games and, frankly, doesn’t need to be. Chasing significantly more polygons now is laborious and mostly just yields diminishing returns. Death Stranding 2’s load times are almost nonexistent, but there’s not another obvious feature that plainly demonstrates how this couldn’t have run on a PS4, at least in the same way as its Metal Gear forebears.

With little to no obvious evidence of a generational leap and a predictable and nearly indistinguishable framework, Death Stranding 2 sounds like a profound disappointment. And it is, in some sense, disappointing in that regard because of the standard Kojima and his teams have set. But that doesn’t take into consideration how it’s still quite a different game when compared to everything else.

Death Stranding has not been emulated in a broader sense across the medium; it’s still a one-of-a-kind entity with its own identity. Even though being a glorified DoorDash deliveryman is omnipresent in both games, there’s still nothing like it. Carefully calculating what gear to bring, how to properly plan around each small bump and flowing river, and just barely scraping through a snowy mountain tundra are all wholly unique feelings only this series is capable of evoking. Kojima Productions, even though it is repeating itself in many ways, has still successfully gamified movement and turned it into an engaging central mechanic.

Death Stranding 2’s narrative similarly doesn’t go against expectations, but the studio’s fingerprints are all over this game. It’s full of incomprehensible jargon, revelations that rely too heavily on convenient contrivances, hilarious moments, and over-the-top and expertly framed action scenes; a true blend of KojiPro’s best traits and worst impulses. There’s a level of heart and earnestness that lets its more egregious and nonsensical indulges slide by without as much scrutiny. For every one of Dollman’s heartfelt conversations with Sam, there are 10 moments where “Chiral” is thrown in front of a word to justify some bizarro anomaly in a nanomachines-esque way, but it’s worth the seemingly unbalanced tradeoff. Ideally, Death Stranding 2 would have gone for a surprising setup to differentiate itself from its predecessor and trimmed down on the self-serving nonsense. However, there’s still a certain flair in KojiPro’s games that’s hard to turn completely away from.

Death Stranding 2, as a whole, benefits from that dichotomy. It does not have its own hook to it like the other sequels from Kojima’s studios and plays it safe by being more Death Stranding. When reinvigoration and leading with new ideas become such core traits for a studio, it’s a tad disheartening when said studio strays from those ideals and goes down a more traditional or normal path for a sequel. But normality is relative, as Death Stranding 2 is still a weird game for freaks who want to slowly walk parcels across timefall-ravaged landscapes as Low Roar’s soft tones play in the background. These soft tones might be an echo, but it’s still an echo from a singular and declarative source.