One Piece is famous for giving even side characters emotionally loaded histories, so when a villain shows up with a strong design, a clear role in an arc, and real impact on the world, it creates an expectation. You want to know what shaped them. Not a sympathy excuse, but a context that explains their worldview and why their cruelty is so specific. The villains who “deserved better” are usually the ones written mostly as obstacles or embodiments of a theme, then moved off the board before the story slows down enough to humanize them.

Videos by ComicBook.com

Sometimes the arc is already packed with reveals, flashbacks, and lore, so the villain’s past gets reduced to a few lines. Sometimes the villain is part of a larger system, and the narrative focuses on the system’s victims instead. That is thematically valid, but it can leave the antagonist feeling like a missed opportunity compared with how rich the rest of the cast can be.

10. Hody Jones

Hody Jones had a strong concept: a fish-man born into a post-Fisher Tiger world, poisoned by second-hand hatred instead of firsthand trauma. The series tells us he grew up in a racist system and simply absorbed that worldview, but it never shows his formative experiences in any meaningful detail. For a villain whose ideology attacks the legacy of Fisher Tiger and Queen Otohime, that lack of depth undercuts the thematic weight of Fish-Man Island. Scenes of him being radicalized, perhaps by older fish-men, or reacting to news of Tiger’s death, would have made his fanaticism more personal and less generic.

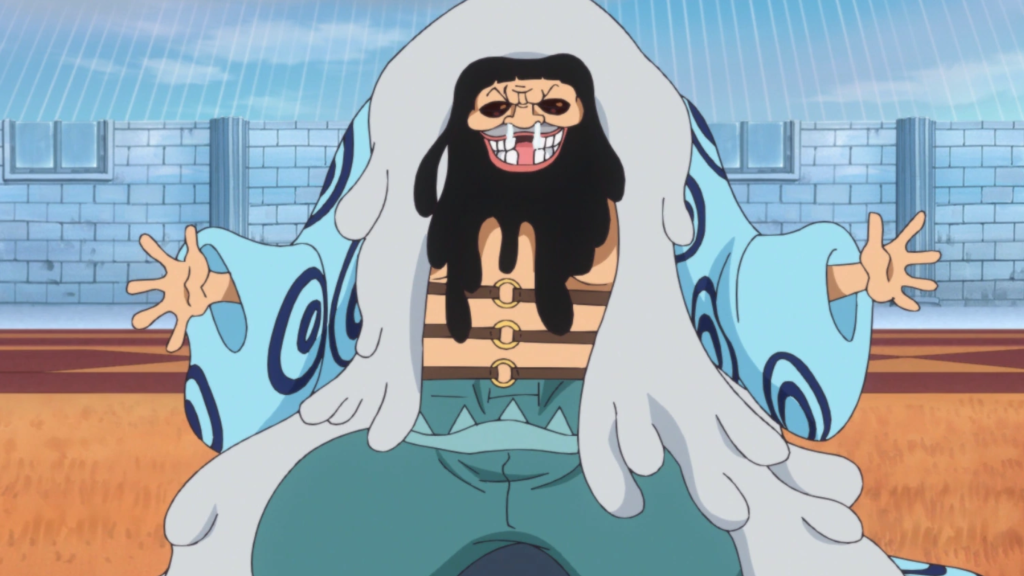

9. Trebol

Trebol works as a grotesque, slime-coated underboss of the Donquixote Family, but his relationship with Doflamingo clearly suggests a deeper emotional layer that Oda only barely touches. We are told that he was one of the four executives who “gave power” to Doffy and fueled his god complex. That premise begs for a flashback that explains why Trebol believed in this child so blindly, what he saw in Doflamingo, and whether he was grooming him as a weapon or genuinely worshipped him. Instead, most of Trebol’s presence is comic cruelty and body horror.

A more fleshed-out backstory might have shown Trebol’s life in the underworld, his own experiences with the Celestial Dragons’ system, and how that led him to cling to Doflamingo as a twisted messiah. Did he lose family to the World Nobles? Did he crave proximity to that same power and try to reclaim it vicariously through Doffy? Without those answers, Trebol comes across as loyal and unhinged, but his devotion lacks a psychological anchor that could have made him chilling rather than just slimy.

8. Caesar Clown

Caesar Clown functions as an entertaining, over-the-top mad scientist, yet his background feels oddly thin for someone deeply involved in so many world-shaping tragedies. We know he was once a colleague of Vegapunk and that their ideological split pushed him toward reckless experimentation, but the series barely scratches the surface of that rivalry. This man gassed an entire island and run experiments on children, and the story treats him mostly as a punchline with flashes of menace.

A more detailed look at his earlier years with Vegapunk and Judge would have enriched him considerably. Showing Caesar at his “almost reasonable” stage, slowly slipping into warped self-justification, could have turned him into one of the most disturbing villains in the series instead of a clownish recurring nuisance.

7. Saint Charlos

Saint Charlos is one of the most viscerally hateable characters in One Piece, yet his backstory is basically a blank slate, and that is a missed opportunity. As a Celestial Dragon, his cruelty obviously comes from a system that raises “gods” to view everyone else as livestock. However, we never see his upbringing, the education he received, or the internal culture of the Holy Land that produced someone this grotesquely entitled. For a story obsessed with how environments shape people, Charlos’ lack of exploration feels like a rare blind spot.

A focused flashback from his childhood in Mary Geoise could have been powerful. Not to redeem him, but to expose the machinery behind the arrogance. For example, scenes of tutors instructing kids that slaves are “things,” or elders rewarding cruelty as proof of “noble blood,” would have reinforced how deeply structural the World Government’s rot is.

6. Warden Magellan

Magellan stands out because he is a villain in function but not in worldview. He believes in order, does his job brutally, and absolutely participates in a horrific prison system. The story hints that he genuinely thinks he is maintaining necessary balance, yet we know almost nothing about how he arrived at that conviction. Impel Down is one of the most morally loaded locations in One Piece, and its top authority figure deserved a richer personal history to match that setting.

Imagine if we had seen Magellan as a young marine or jailer, confronted with pirates who destroyed his home or killed people he cared about. That kind of backstory could have justified his belief that “extreme measures” are necessary. The constant poisoning and health issues from his Devil Fruit also raise psychological questions. Did he accept that power as a self-sacrifice, or did he misjudge it and then double down on his role out of guilt and obligation? The series never answers any of this, so Magellan ends up feeling like a compelling concept parked in the background of a chaotic jailbreak.

5. Gecko Moria

Gecko Moria clearly has the skeleton of a great tragic villain. He once fought Kaido in the New World and lost everything, including his crew, which left him hollow and obsessed with building a disposable zombie army. The problem is that we are mostly told this through exposition instead of being allowed to feel it through a substantial flashback. Thriller Bark leans heavily on horror comedy, and in the process, Moria’s psychological collapse gets skimmed rather than properly explored.

A full flashback arc to the Rumba Pirates-style destruction of the Moria Pirates could have been devastating. Seeing his crew’s personalities, their hopes of conquering the New World, and then watching Kaido systematically crush them would have given real emotional weight to his laziness and nihilism.

4. Rob Lucci

Rob Lucci is framed as a “born killer,” someone the World Government noticed at a young age and molded into an assassin. The Enies Lobby flashback shows a glimpse of his warped sense of justice. That kid slaughtering hostages and pirates alike is deeply memorable, yet it feels like just the first chapter of a story we never truly get. For someone who represents the darkest edge of “Absolute Justice,” his early life and recruitment into CP9 deserve far more detail.

We never learn what kind of family he had, or if he even remembers anything outside of serving the government. Was he a child the system rescued and then weaponized, or did he come from inside the nobility or a poor war-torn nation? CP0-era Lucci adds an extra layer, because he still works for the same institution despite witnessing its corruption.

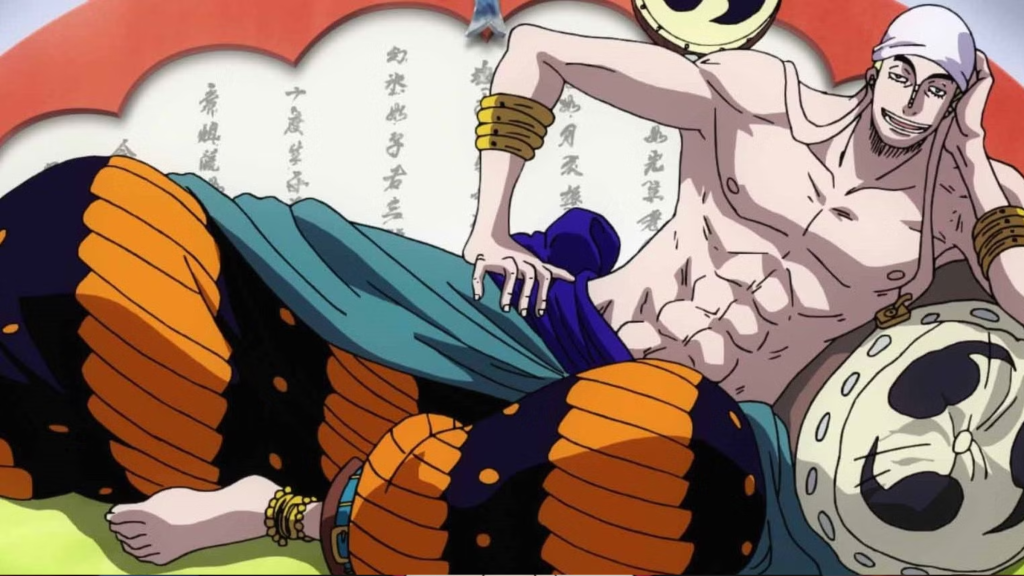

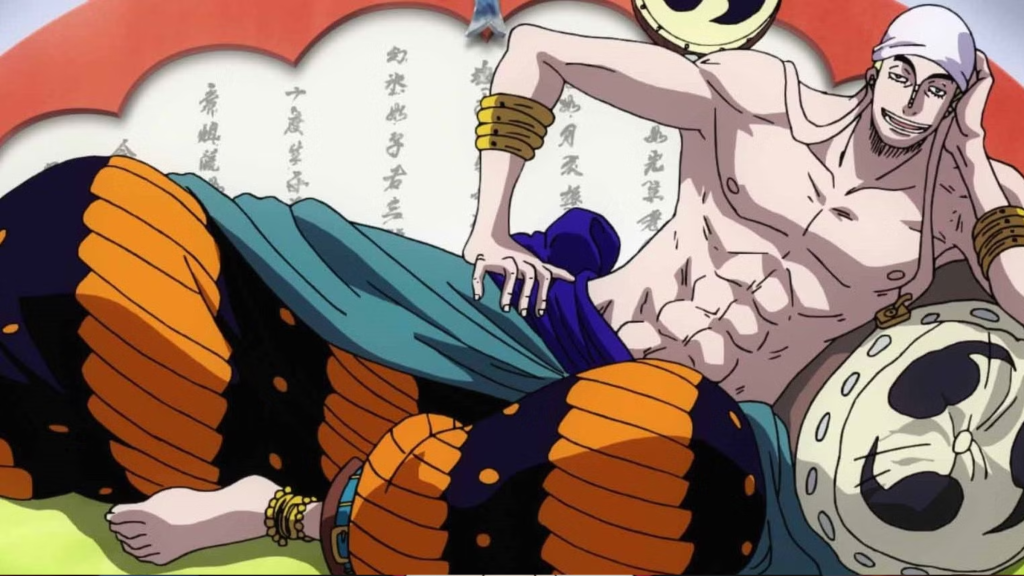

3. Enel

Enel might be one of One Piece’s most iconic early villains, and yet we know shockingly little about what shaped his god complex. We are told he destroyed his homeland, Birka, and then seized control of Skypiea. That is a huge act of genocide-level violence, and it mostly exists as a line in the lore rather than a fully dramatized piece of his character. A man who casually erases his own people and calls himself “God” must have some formative ideological path, but the series glosses over it.

Seeing his first moments of self-deification, his early followers, and the destruction of Birka would have made Skypiea’s conflict more than just “Luffy punches a god-shaped narcissist.” It would have deepened Enel into a case study of unchecked power and religious delusion.

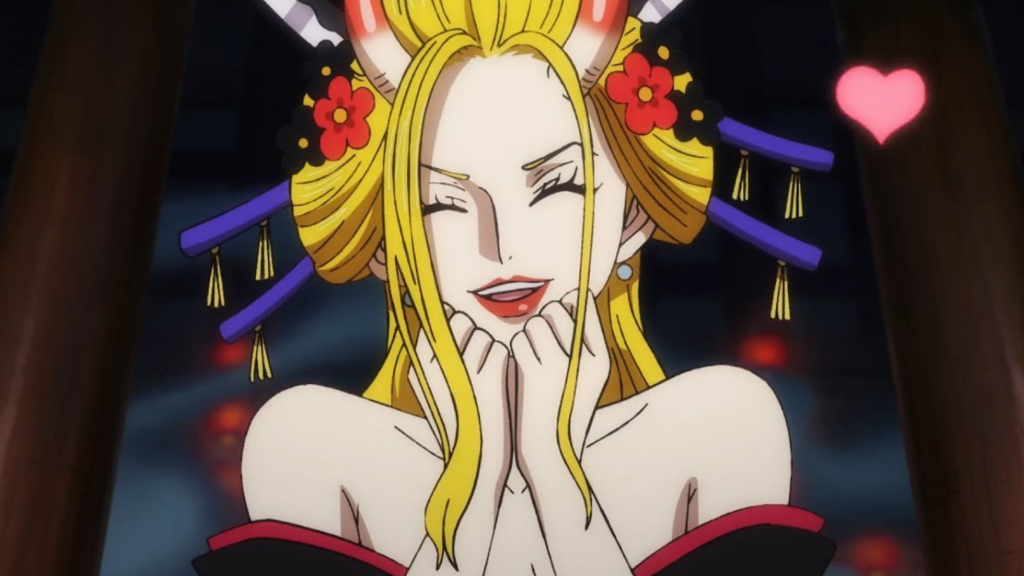

2. Black Maria

Black Maria’s design and personality are striking, and her fight with Robin carries serious emotional weight, yet her history is almost blank. As a giant woman seemingly integrated into Wano’s underworld, she raises fascinating questions: how did a non-Wano giant end up there, what drew her into Kaido’s crew, and why does she cling to that environment? Her cruelty toward Robin and Sanji hints at deep-seated insecurity and a taste for manipulation, but we have no concrete biographical context to ground it.

Giants in One Piece often face prejudice or exoticization, and Black Maria’s brothel aesthetic implies a life of transactional relationships and emotional walls. Perhaps she survived exploitation by choosing to become the exploiter. Maybe she found a twisted sense of belonging among the Beast Pirates, where strength and intimidation are currency.

1. Kaido

Kaido clearly matters to the grand narrative: one of the Four Emperors, a symbol of unbreakable strength, and a man obsessed with staging “the greatest war the world has ever seen.” The problem lies in how his backstory is handled. We do get a flashback, but it is brief and fragmented. It hints at a life of constant exploitation, first as a child soldier of the Vodka Kingdom, then as a beast of war for the World Government, yet it stops just when it should dig deepest. The central question of why Kaido craves a glorious death and apocalyptic conflict is never given the thorough emotional exploration it deserves.

Watching him as a child drafted into endless wars, betrayed by kings, and sold out to the Marines could have built a clearer line from “war tool” to “war worshipper.” His obsession with Joy Boy and his suicidal tendencies imply profound despair, but the story only gestures at that despair instead of dwelling on it. Wano treats Kaido as the final boss of an era, yet his inner life feels sketched rather than fully painted.

What do you think? Leave a comment below and join the conversation now in the ComicBook Forum!